With the consolidation of the maritime commercial route of the Manila Galleon in 1565, innovative artistic forms were introduced to New Spain. These objects—including porcelain, lacquer, and silks—quickly had an impact on local taste. Among these novel objects were biombos, or folding screens, Japanese imports that were soon adapted by local artists to New Spanish tastes. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the folding screen became a symbol of refinement and an almost ubiquitous feature of colonial interiors.

Folding screens were then reinvented in the twentieth century by Mexican modern interior designers and architects. Some drew on the biombo’s links to the colonial past, while other designers saw them as modernist pieces of furniture, stripped down to their barest elements. In Mexico, both of these ways of understanding the biombo were influenced by history, reinforced by famed and prominent screens that were being collected or displayed in museums as national treasures.

This essay identifies three ways in which to explore the biombo in modern interiors. First, antique screens appeared in modern interiors as status objects that reaffirmed their owners’ links to the colonial past. Second, biombos were used as supports for artistic expressions that sought to vindicate Mexican folk arts and traditions: In this case, the format of the screen itself may have contributed to the perceived Mexicanness of the object (in other words, these artists may have seen the biombo as a traditionally Mexican support). Finally, modern screens were stripped of their most obvious references to the past or tradition: Lacking iconography, they became vehicles for different architectural and material discourses. At the same time, their function changed, and they were sometimes transformed into a fixed architectural element, becoming an extension of the building and abandoning the portability that had originally contributed to their popularity.

Origins

The word “biombo” is a corruption of the Japanese byōbu (wind wall), and it remains the only term used in Mexico today, demonstrating its enduring link to Asia.1 Folding screens were first introduced to the Iberian world as diplomatic gifts from Japanese envoys in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries and were soon shipped across the Pacific via the Manila Galleon to eager consumers in New Spain.2 The first screens to arrive were made of layered paper stretched over a wooden frame and adorned with ink washes and gold ornamentation, trimmed by lacquer and silk edging. Almost immediately on arriving in the Mexican capital, local artists began to reinvent the Japanese screen according to local tastes using readily available materials like cotton canvas and oil paints.3 In the hands of New Spain’s painters, biombos became important supports for secular subjects in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in contrast to the religious themes that otherwise predominated. They often featured historical scenes like the Conquest of Mexico, literary characters, mythological allegories, landscapes, and scenes of leisurely life (fêtes galantes), but they could also be covered with decorative patterns, especially on the reverse face. Because they were typically painted with complex iconographic programs, biombos were considered art objects rather than furniture in the colonial period.4

Whether made locally or imported, the screens’ association with not only the luxury and fantasy of Asia but also elevated rank and courtly power made them attractive to the newly enriched nobility of New Spain, and their popularity radiated outward to the rest of colonial society. They were hallmarks of the remarkable cosmopolitanism of New Spanish consumers, and to own one was an explicit statement of that sophistication. Within the colonial home, biombos were typically placed around the estrado, a women’s sitting room that often displayed a family’s most luxurious objects. Biombos became such an important part of interior design that they were portrayed in several ex-votos and casta paintings. One such example can be seen in an eighteenth-century ex-voto where the biombo serves to protect a patient undergoing surgery (fig. 1). The pictured eight-leaf lacquered screen tells us how established the use of this object was by the eighteenth century, as well as its position and scale within the home.

While the biombo never lost its link to Asia—in 1726, the Diccionario de Autoridades still noted: “It is a treasure that came to us from China or Japan” (Es alhaja que nos vino modernamente de la China o Japón)—its reinterpretation by local artists transformed it into a fundamentally New Spanish object.5 With the end of the galleon trade, the fashion for Asian goods diminished, and over the course of the nineteenth century, the production of biombos rapidly declined. Biombos ceased to be decorated with sophisticated programs drawn from mythology or landscape painting, instead becoming folk objects featuring phytomorphic or abstract decorations.

Repurposing Antique Screens

Until rather recently, historians of Mexican furniture—few though they were—paid less attention to the biombo than to furnishings like chests, chairs, or tables. Abelardo Carrillo y Gariel’s Evolución del mueble en México (1957) was one of the first studies to trace a continuous and convincing history of furniture in Mexico, including prehispanic versions. He focused on chairs and other seating and relegated the screen to the end of the book, including only three examples. One of them is a famous eighteenth-century biombo depicting a sarao (a type of courtly dance) in a garden by Miguel Gerónimo Zendejas (1724–1815), now in the National Museum of History in Mexico City. While undoubtedly an important artwork, Gariel ignores other examples of great historical importance and omits references to the evolution of the biombo, which he includes for chairs and tables.6 This is common in publications dedicated to the history of Mexican furniture at mid-century: The biombo is acknowledged as an important historic object, but without information on its development, it appears immutable. Only later would designers and historians acknowledge the evolution of screens and their links to contemporary production.

This early history reminds us that one way the painted biombo was incorporated into modern Mexican interior design was as an antique. Considered both a work of art and a relic of the past, the screen lost its function of demarcating space within the home. Instead, these objects were displayed as symbols of high social status, protagonists in the construction of interiors that sought to project tradition and aristocratic ancestry. For those not lucky or wellborn enough to inherit one, biombos were readily available from Mexico City’s antique dealers. An alternative was to install a neocolonial screen of contemporary manufacture. In either case, these screens shared the same purpose: explicitly claiming the prestige associated with colonial institutions of power such as the Church or the Crown, in direct opposition to the post-revolutionary discourses that privileged the prehispanic past and the Indigenous origins of Mexico as the foundation of a national identity.7

A good example of the use of the biombo as a legitimizing element of class and social status can be found in the house of Manuel Barbachano, a famous film producer and director. Located in San Ángel, a colonial village in the southern part of Mexico City, it was decorated in 1957 by the noted interior designer Arturo Pani (1915–1981). He often drew inspiration from eighteenth-century rococo and nineteenth-century Beaux Arts traditions, streamlining them rather than copying them slavishly.8 For the Barbachano house, he continued to reference the past, using a reproduction of the Zendejas sarao biombo to anchor a large interior space (fig. 2). The screen took a leading role at the center of the main room of the house, where its visible position reaffirmed elegance and tradition, referencing a specific antique displayed in a museum dedicated to Mexican history.

While designers like Pani left the biombo as a freestanding element, other designers chose to wall-mount biombos, simultaneously reaffirming the screens’ position as artworks while removing their function as partitions. This mode of display emphasizes their iconographic and symbolic messages but also conceals one side of these often dual-faced objects. It was in this manner that interior design books and magazines from mid-century promoted the use of folding screens: displayed flat and transformed into paintings. One magazine stated that once wall-mounted, a biombo could function as “a sort of mural.”9 In designing the house of the elite Corcuera family, José Gómez de Parada installed a ten-panel biombo featuring a scene of a fête galante in Tlalpan and attributed to Miguel Cabrera, against a wall in the dining room alongside a collection of New Spanish masterworks (fig. 3). Other interior designers followed this new way of displaying antiques (fig. 4).

Images of mid-century interiors featuring colonial biombos were popularized in a series of books dedicated to Mexican interiors edited by the American architect Verna Cook Shipway and her husband, Warren Shipway, between 1960 and 1970. As Catherine Ettinger has discussed, the Shipways were pioneers, and their books document not only interiors but furniture design, gardens and topiary, and architectural elements in towns like Cuernavaca, Taxco, Guanajuato, and Mexico City, where many American expatriates lived. They promoted a “Mexican” language of interior design in which antiques and religious art coexisted with modern furniture, usually in neocolonial residences, although more modern interiors were sometimes included.10 These books are useful not only to see how antiques were being deployed but to know how taste was being shaped for a broad audience and coalescing around a standardized “Mexican interior.”

One book in the series, Mexican Interiors (1962), included sections dedicated to architectural typologies, decoration, crafts, and furniture such as biombos, where colonial and revival examples are shown indistinctly.11 Sometimes the two were mixed, creating pastiches where neocolonial wooden screens incorporated retablos or paintings of saints on tin (fig. 5). This is proof of the popularity of the screens and their perceived Mexican quality, which was being exploited by designers and collectors to forge an interior design style that bridged the modern and colonial periods.

In the 1970s, antique biombos also appeared in the country’s leading design magazine: Diseño. Sugerencias para Vivir Mejor (Design: Ideas for better living) (1969–75), the first Mexican publication dedicated to interior design. While short-lived, the magazine was a beacon for freedom of speech amid the official repression against students and political dissidents in this period: It portrayed interiors of all social classes but frequently highlighted the homes of members of Mexico’s art world.12 Diseño showed folding screens in several issues, including a photo essay featuring the Barbachano home, proof of the continued relevancy of both Pani’s interior design and biombos to a wide audience (fig. 6).

The biombo was promoted as a useful element in interior decoration, as well as an example of what to collect. It was so ubiquitous that the editors even published instructions for how to make one’s own folding screen, noting its long history as a type of furniture.13 In another essay focused on biombos, published in August 1970, the magazine explained the two roles of these screens, both traditional and current:

In classic interiors the biombo is, generally, antique and in the case of being a work of art, it gives more relevancy to its surroundings. . . . The concept of the biombo itself and its usefulness have changed a lot in recent times, it is no longer just a means of protecting something from prying eyes. At present, it is an element of decoration with a life of its own that is used in different ways.14

The Biombo as Support

Although japonisme had been an important part of colonial Mexican visual culture, the renewed fervor for Japan that struck the West in the nineteenth century did not find fertile ground in Mexico. By the beginning of the twentieth century, only a few of its intellectuals had visited Japan, and the influence of the Asian nation on design and architecture was negligible. The multi-hyphenate José Juan Tablada (poet, art critic, diplomat, and journalist) was a rare exception, and while his enthusiasm for Japanese art and culture was great, it was not part of a larger wave.15 The relevance of the biombo in this period resulted from its position as an icon of Mexican material culture rather than as a Japanese export.

Early-twentieth-century artists used the format of the biombo as a support for more nationalist artistic expressions. One of the earliest examples of this impulse is a 1929 screen by Roberto Montenegro (1885–1968), one of the pioneers of the muralist movement in the early 1920s and a close collaborator of José Vasconcelos, Secretary of Public Education and intellectual architect of the new Mexican art.16 Across six panels, Montenegro depicted a map of the Mexican Republic in which images of popular arts, flora and fauna, and typical dances are placed across the landscape, as if they were part of the Mexican geography (fig. 7). A direct prototype was the work of nineteenth-century cartographer Antonio García Cubas, who used this strategy to depict Mexico’s resources and encourage economic development, partly for foreign audiences.17 As Delia Cosentino and Adriana Zavala have shown, the use of a screen was a way of elevating the popular arts (illustrated on the map) to the field of fine arts, a crucial part of the post-revolutionary discourse that shaped the early years of Mexican muralism.18 This biombo was painted the same year that Montenegro, together with diplomat Moisés Sáenz, founded the Museum of Popular Arts in Mexico City. This work would affirm the status of the biombo as a Mexican folk art object divorced from its Japanese origins.19

Montenegro repeated this formula in 1951: Across four panels, he reproduced a lithograph of the bay of Acapulco from 1628, a work by Dutch artist Adrian Boot. Montenegro even copied the cartouche—an element present in colonial biombos that narrated battles or showed local fiestas—that held a legend to the map. In doing so, Montenegro referenced the tradition of mestizo and Indigenous artists in New Spain who reproduced European designs entirely, including cartouches and other editorial details like engravers’ signatures.20

Another of these pictorial screens was painted by the Austrian American artist, curator, and collector René d’Harnoncourt. D’Harnoncourt arrived in Mexico in 1925, where he met the antiquarian and dealer Frederick Davis, with whom he traveled the country buying and studying antiques and popular arts.21 Painted in 1931, View of Miacatlán measures about five feet tall and shows the bucolic and idealized Indigenous village of Miacatlán, located in the state of Morelos, south of Mexico City. D’Harnoncourt emphasized the traditional houses and local residents, ignoring the seventeenth-century church and nineteenth-century buildings in the town. An inscription at the bottom of the biombo recalls less the cartouches on colonial screens than those on popular ex-votos that detail miraculous events. D’Harnoncourt was certainly familiar with the ex-voto tradition, since he included several examples in the exhibition Mexican Arts that he curated for The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1930. He included no biombos in that show but surely knew of them through Davis’s shop.22 It recalls colonial biombos showing Indigenous life, like the famous seventeenth-century screen at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art showing festivities, including voladores, at an Indigenous wedding. In View of Miacatlán, however, d’Harnoncourt mixed colonial and folk art to create something new.

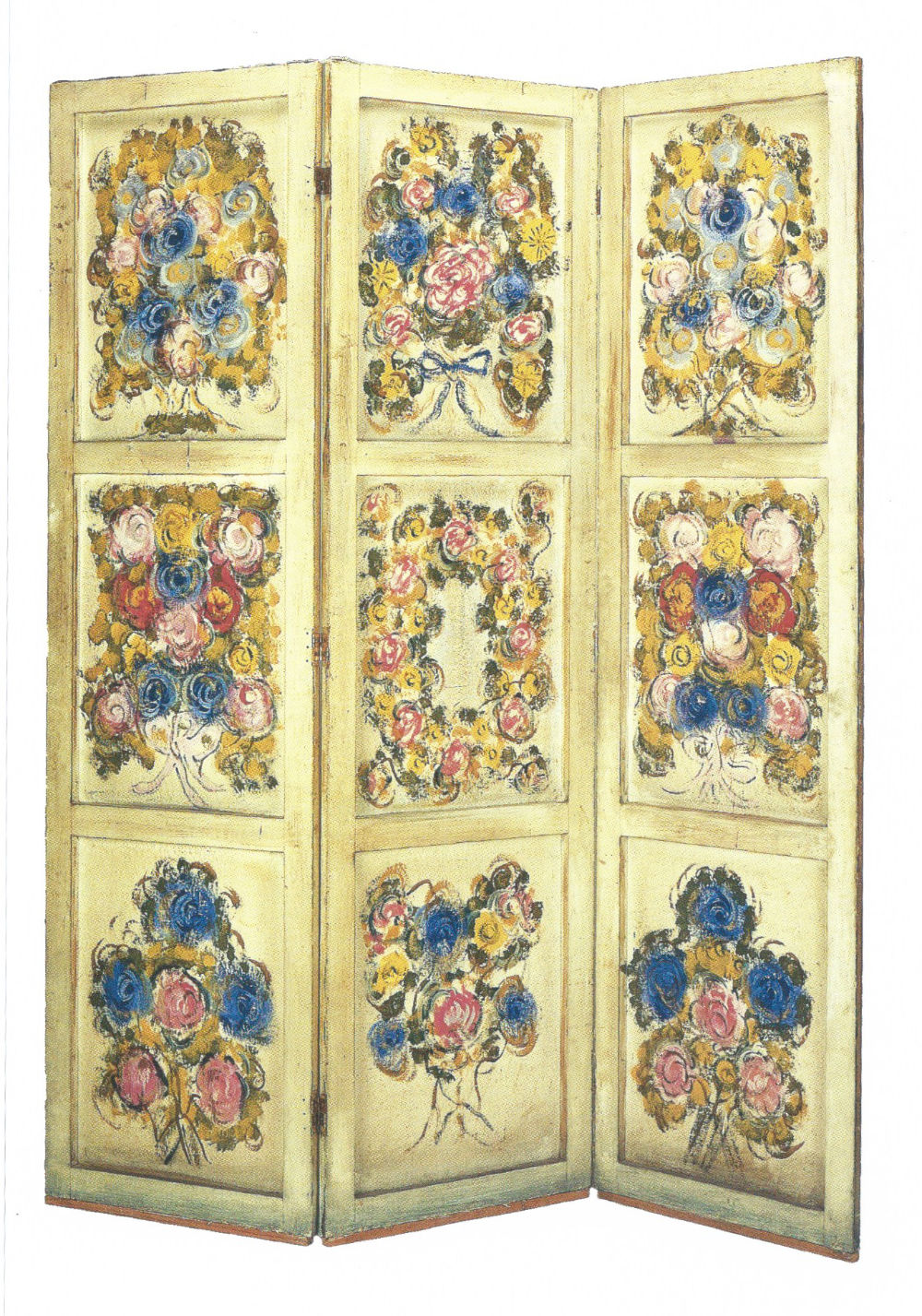

In subsequent decades, other artists revisited the biombo as a support full of symbolic and historical meaning. The antique dealer and collector Jesús Reyes Ferreira (1880–1977), known as Chucho Reyes—a leading figure in Mexico City’s art scene at mid-century—created a series of wooden biombos in the 1950s.23 Reyes decorated them with his characteristic thick and quickly applied brushstrokes, depicting vases and baskets of flowers along with birds in a semiabstract garden (fig. 8). They resemble the works on paper he was creating at the same time (originally designed as wrapping paper for the fragile antiques he sold), which, as in this example, referenced vernacular painting and folk decorations, such as those found on ceramic tiles used in eighteenth-century religious architecture.

Around the same time, other prominent artists such as David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974) were experimenting with the folding screen format. In 1960, Siqueiros was apprehended and imprisoned by the government for his support of union leaders and the Communist Party in a political climate marked by repression and official paranoia. While in prison, he painted several biombos as backdrops for plays staged by the inmates, using them as vehicles for social criticism.24 Lacking references to popular arts, Siqueiros relied on the familiarity of the typology in the Mexican collective imagination but also used screens because of their mobile quality, an especially useful feature when applied to set design. In a maquette from 1965, one year after he was released from prison, Siqueiros produced a series of miniature biombos covered with abstract gestural brushwork with thick layers of paint (fig. 9). In these experimental works, the folds of the screens and their freestanding quality served the artist as starting points for spatial exploration, playing with perspective and light.

The fact that Siqueiros used the biombo format not only proves the relentless experimental drive of the artist but also the uninterrupted presence of the folding screen in Mexican life. Siqueiros created several of these maquettes, probably as experiments that later influenced major works of architecture like the Polyforum in Mexico City or his studio “La Tallera” in Cuernavaca, where leaning walls with corners at acute angles were intensified by the painter’s abstract compositions. Thus, biombos remained a typology associated with art, constantly being revisited as a support for painting, even for abstract and experimental works of art, only in this case, completely disengaged from domestic interiors.

The Architectural Screen

At mid-century, several interior and furniture designers, including Arturo Pani—whose use of antiques has been discussed—and Luis Barragán (1902–1988), whose plain biombos are perhaps the most well-known, brought the screen into the modern home. In the process, they were drained of iconography, and materiality became more important. In their mid-century revival, biombos were considered part of the architectural space, especially their impact on spatial movement and light.

Almost every modern Mexican designer and architect designed at least one biombo; the format proved useful in displaying a versatile vocabulary. Pani, for example, created screens using diverse styles, sometimes looking back to classical Renaissance motifs, while also showing strong influence from the streamlined forms of Scandinavian design. Other designers more explicitly referenced the Asian origins of biombos. The US-born designer Frank Kyle, who moved to Mexico in the early 1950s, drew on his interest in Japanese forms and typologies to create several biombos, some featuring hidden joints in unexpected places, brass ornaments, and Japanese imagery. The decorator and designer Eugenio Escudero, a favorite of Mexico’s jet set, was also fond of transforming screens into abstract, transparent, and architectural sculptures.25

Of all of these modernists, however, it was Barragán who really redefined the screen, making it a key element in his innovative, spare interiors, using it to divide spaces and shift our perception of light. Barragán reinvented antique furniture typologies throughout his career, as in the case of the lectern, which he streamlined in cedar wood while leaving its medieval origins obvious. He also reformulated low chairs of wood and woven palm, Talavera vessels, and even petates (woven bedrolls), making slight changes in proportions and materials but preserving ancestral techniques and functions and displaying them in avant-garde interiors, creating a modern and international language that simultaneously referenced Mexican sources. Barragán abstracted Mexican vernacular furniture with a surprising level of synthesis and sobriety, similar to what Anni Albers did with Mexican textiles or what Clara Porset (1895–1981) did with the traditional butaque seat.26

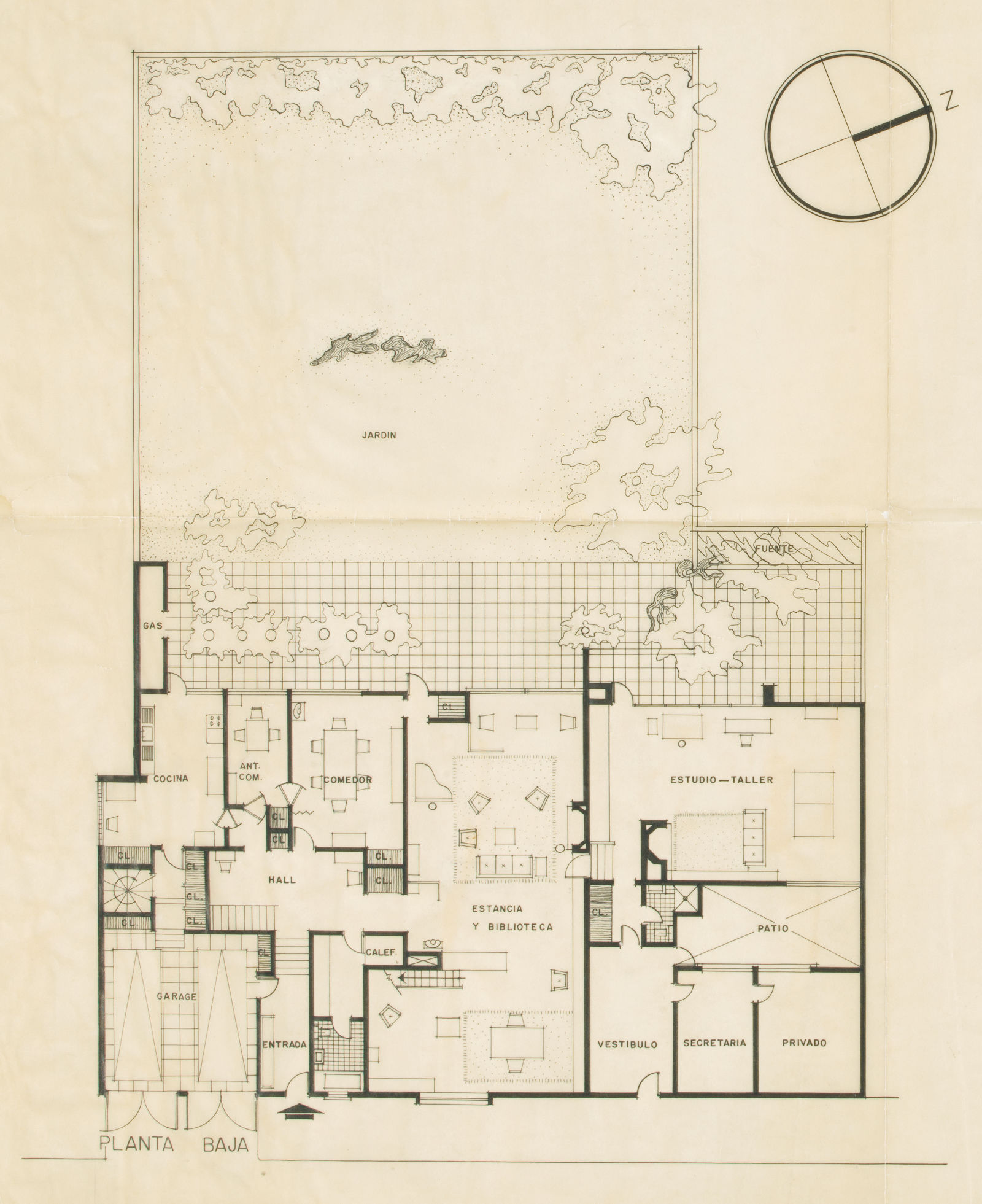

In fact, screens play an important role in Barragán’s interiors, where he used them as an articulated extension of the low walls that divide rooms and spaces without interrupting the flow of light reflected across the double-height ceilings. Often considered mere background elements, these screens are crucial to understanding the architect’s interior design, not least because they remain largely in situ, unlike the other screens that have been discussed so far (fig. 10). Indeed, screens were already sited in Barragán’s original floor plan (indicated by zig-zag lines), proving that the architect thought of them as an architectural feature, not to be moved and as important as any wall (fig. 11).

Perhaps the first of these screens to be made was the one in the living room in his house-studio in Tacubaya, a historic neighborhood near Chapultepec Park, completed in 1948 (fig. 12).27 It consists of four panels, each just over eight feet high and just over two feet wide (almost ten feet wide if fully extended). The height of the screen is almost the same as the wall that divides the living room from the entry hall, creating a space reduced in width although without a ceiling, providing intimacy without sacrificing luminosity or the monumentality that the double-height ceiling gives the space. The panels are made of wooden frames covered by sheets of parchment, an old-fashioned translucent material (common in medieval manuscripts) that makes the screen both a reflective surface and a protective wall. Barragán paid close attention to the meaning and history of materials, using them to create a cohesive atmosphere, from the exterior of the unpainted facade to the smallest detail inside. He thus frequently used parchment in his designs, including for lamp shades: Its ivory white color is similar to the raw cotton textiles (manta de cielo) and undecorated white Talavera ceramics that Barragán also favored.

In the library, Barragán placed another, more modest three-panel screen in which the wooden supports are covered by white “manta.” It measures six-and-a-half feet tall, exactly the same as the wooden wall that projects from the adjacent monumental bookshelf. Here the screen extends the wall and divides the bookshelf, creating a more intimate reading room, equipped with couches, a table, and chairs. The screen also reflects the natural light that enters through a large square window with frosted glass. These elements combined provide the space with an intense but soft light, without shadows or colors that might inhibit reading or distract one from concentration. Two other screens were installed in the more intimate spaces in the upper floor, both made of wood and white manta. Those screens are a bit lower, just under six-and-a-half feet, scaled, perhaps, to the architect, who was just over six feet tall.

Barragán also designed biombos for houses he built for private clients, where they play the same role as in his own home. The Casa Prieto López, the first he built in the elite housing project known as the Jardines del Pedregal de San Ángel, also completed in 1948, included a six-panel screen covered in fabric, with the same dimensions as the one in his library.28

By the mid-1950s, Barragán had mastered the use of biombos as a defining architectural element strategically placed to change light, give privacy, extend walls, and create dialogues with the furniture. In 1955, for the Casa Gálvez, he designed three fabric-covered screens that remain in situ today. We see a standardization of materials, measurements, and function—but not of color. In the main living areas, he used raw white manta, but for a biombo in a reading space, more private and less well-lit, he selected an intense fuchsia fabric. Cristina Gálvez recalls that both the architect and her father (the client) referred to the hedge in the garden as a biombo of jasmines, marking the path to discover the mysterious garden and linking the interiors with the exterior.29

For Barragán, the materiality of these screens was of the utmost importance; their materials and handmade facture connected them to folk art and the colonial past, allowing him to modernize tradition. Almost at the same time Barragán was furnishing his house in Tacubaya, Charles (1907–1978) and Ray (1912–1988) Eames were designing their own folding screen but moving in an opposite direction, creating an industrially produced object with uniform and smooth modular plywood sheets joined with hidden hinges. Although the biombo typology was widespread and contemporary designers were using it in different parts of the world, its symbolic charge was different in Mexico, where even in the most abstract examples it was linked to New Spain.

Barragán’s use of screens and their incursion into modernist architectural spaces had a powerful impact on his circle of friends and collaborators. A fuchsia biombo was placed in the renovated house of Chucho Reyes, a project not officially recognized as Barragán’s work but on which both collaborated. Architect Juan Sordo Madaleno (1916–1985), with whom Barragán worked on many projects, also incorporated screens in his interiors, where they guide the flow of users and light. In his office, a heavy folding wooden door partially divided the room (fig. 13). This might be thought of as a sort of biombo, now permanently fixed to the wall and continuing the use of natural wood.30

This research has also identified the use of biombos in commercial spaces, like the Cine París, built in 1954 by Sordo Madaleno. It was one of the most modern movie theaters at the time, located on the Paseo de la Reforma (it has since been torn down).31 A monumental screen divided the bar, which was furnished by Clara Porset, from access to the theater (fig. 14). Unlike those in Barragán’s houses, here the biombo is used as an opaque barrier whose white, square panels serve as a support for reproductions of etchings or drawings by Picasso.

The monumental openwork steel screen on the main entrance of the Camino Real Hotel, built in 1968 by architect Ricardo Legorreta (1931–2011) for the Mexico City Olympics, might also be understood in the context of this history of the modern biombo (fig. 15). Legorreta commissioned Mathias Goeritz (1915–1990) to design this feature, which has long been understood in terms of plastic or visual integration, the interrelationship of sculpture and architecture that largely defined mid-century architecture in Mexico. Goeritz created a monumental lattice; although originally black, it later acquired its characteristic bright pink—recalling the fuschia biombos in Barragan’s houses—that mediates between the street and a courtyard that leads to the hotel lobby. Its position is fixed, yet it gives the impression that it is an articulated object that could well move or change position.32

Biombos continued to be part of Mexican art history long after the last galleon docked in the port of Acapulco in 1815. Consistently revised and reinvented, the Japanese byōbu quickly became a part of New Spanish identity and therefore of the new Mexican pantheon of objects and supports after the Mexican Revolution, later to be exploited to its limits and finally becoming an abstract and even architectural object thanks to the experimentation of the modern movement in Mexico. Biombos are one of the few testimonies of the intense transpacific trade that is still a part of the Mexican vernacular, a long and ongoing travel with unexpected results.

Notes

-

Teresa Castelló Yturbide, Biombos mexicanos (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1970), 11. ↩︎

-

Sofia Sanabrais, “The Biombo or Folding Screen in Colonial Mexico,” in Asia & Spanish America: Trans-Pacific Artistic & Cultural Exchange, 1500–1850, ed. Donna Pierce and Ronald Otsuka (Mayer Center for Pre-Columbian and Spanish Colonial Art at the Denver Art Museum, 2009), 71; Sanabrais, “From Byōbu to Biombo: The Transformation of the Japanese Folding Screen in Colonial Mexico,” Art History 38, no. 4 (2015): 783–84. ↩︎

-

Sanabrais, “From Byōbu,” 785. ↩︎

-

Sanabrais, “The Biombo,” 83. ↩︎

-

Sanabrais, “From Byōbu,” 790. Original found in Diccionario de la lengua castellana . . ., vol. 1 (Francisco del Hierro, 1726), 609. ↩︎

-

Abelardo Carrillo y Gariel, Evolución del mueble en México (Dirección de Monumentos Coloniales, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia y Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1957), 165–67. ↩︎

-

This discussion raged for years among architects and historians. Some found in colonial architecture and furniture design a mixture of European and Indigenous features, making it “a true Mexican style.” As time went on, only the most conservative sectors of society were still building and furnishing homes and office buildings in this fashion, as opposed to the functionalism associated with socialist ideas or, later, following the trend for folk art popular among the jet set. See Jorge Alberto Manrique, “México se quiere otra vez barroco,” in Arquitectura neocolonial: América Latina, Caribe, Estados Unidos, ed. Aracy Amaral (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1994), 39. ↩︎

-

“Así vive Barbachano Ponce,” Diseño. Sugerencias para Vivir Mejor 2, no. 10 (1970): 68–73. ↩︎

-

Diseño. Sugerencias para Vivir Mejor 2, no. 16 (1970): 23. ↩︎

-

The titles are The Mexican House Old and New (1960); Mexican Interiors: Mexican Homes of Today (1964); Decorative Design in Mexican Homes (1970); and Houses of Mexico: Origins and Traditions (1970). See Catherine Ettinger, “Un discurso de modernidad y tradición, Verna Cook Shipway y la representación de la casa mexicana,”Academia XXII 5, no. 8 (2015): 75–93. ↩︎

-

Verna Cook Shipway and Warren Shipway, Mexican Interiors (Architectural Book Publishing Co., 1962), 71–74. ↩︎

-

Aldo Solano Rojas, “Arte, coleccionismo y decoración: la revista Diseño. Sugerencias para Vivir Mejor (1969-1975),” Bibliographica 4, no. 1 (2021): 168–92. ↩︎

-

Álvaro de Regil, “La belleza funcional del mueble moderno. El biombo, clave de separar sin dividir,” Diseño. Sugerencias para Vivir Mejor 4, no. 45 (1973): 46–49. ↩︎

-

“Bienvenidos a los dobleces,” Diseño. Sugerencias para Vivir Mejor (August 1970): 30–32. Translated by the author. ↩︎

-

Amaury A. García Rodríguez, “El Japón quimérico y maravilloso de José Juan Tablada. Una evaluación desde las artes visuales,” in Pasajero 21. El Japón de Tablada, ed. Miguel Fernández Félix (INBAL, 2019), 67. ↩︎

-

Claude Fell, José Vasconcelos: los años del águila (1920-1925): educación, cultura e iberoamericanismo en el México postrevolucionario (UNAM, 1989), 384. ↩︎

-

On the key role of cartographers in the construction of Mexican identity in late nineteenth century, see Amaya Larrucea Garritz, País y paisaje. Dos invenciones del siglo XIX mexicano (UNAM, Facultad de Arquitectura, 2016), 92. ↩︎

-

Adriana Zavala and Delia Cosentino, Resurrecting Tenochtitlan: Imagining the Aztec Capital in Modern Mexico City (University of Texas Press, 2023), 85. ↩︎

-

Rick A. López, Crafting Mexico: Intellectuals, Artisans, and the State After the Revolution (Duke University Press, 2010), 157. ↩︎

-

My thanks to Kathryn Santner for pointing this out. ↩︎

-

López, Crafting Mexico, 111. ↩︎

-

Richard Townsend, Indian Art of the Americas at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 2016), 17. D’Harnoncourt’s biombo is now part of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (2022-72-151). ↩︎

-

See Lily Kassner, Chucho Reyes (Editorial RM, 2002). ↩︎

-

Elena Poniatowska, Siqueiros en Lecumberri: una lección de dignidad, 1960-1964 (CONACULTA, INBAL, 1999), 19–24. ↩︎

-

Both Kyle and Escudero still remain under-researched. Some bits of information can be found in catalogs of the period, but monographs on each are still necessary. ↩︎

-

See Ana Elena Mallet, Clara Porset: Butaque (Museum of Modern Art, 2024); and Anni Albers, Brenda Danilowitz, and Juan Tovar, Anni Albers: Del Diseño (Alias, 2019). ↩︎

-

Louise Noelle, Luis Barragán. Búsqueda y creatividad (UNAM, 1996), 26. ↩︎

-

Sadly this screen was sold, and its whereabouts are now unknown. Noelle, Luis Barragán, 141. ↩︎

-

Interview with Cristina Gálvez by the author, Chimalistac, Mexico City, November 1, 2024. ↩︎

-

Louise Noelle, Arquitectos contemporáneos de México (Trillas, 1999), 142. ↩︎

-

Noelle, Arquitectos contemporáneos, 146. ↩︎

-

Jennifer Josten, Mathias Goeritz: Modernist Art and Architecture in Cold War Mexico (Yale University Press, 2018), 238. ↩︎