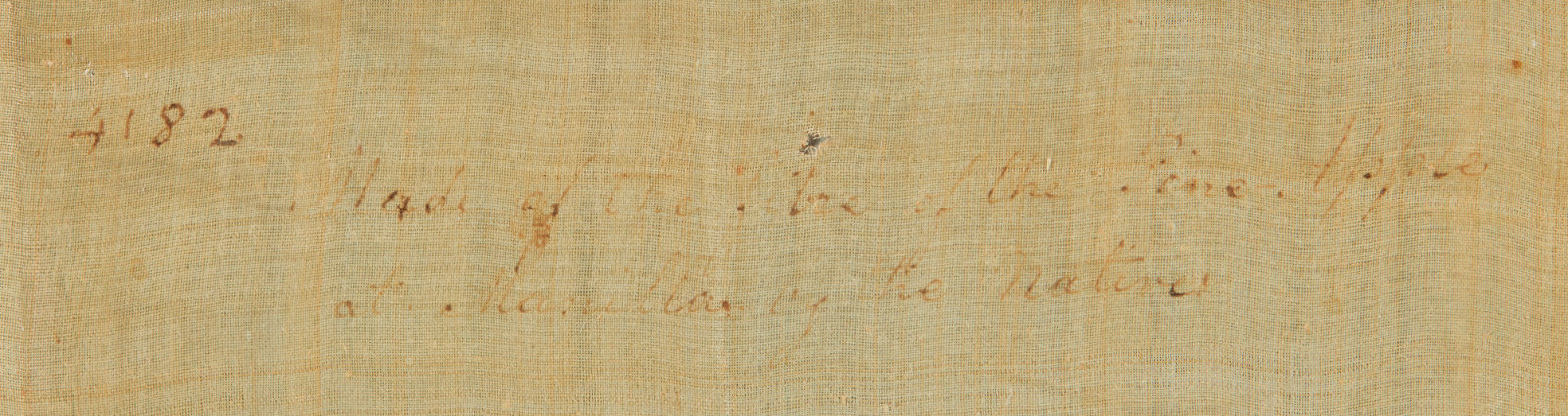

In 1830, Captain Joseph Jenkins Knapp Jr. (1803–1830) donated a square piece of Philippine piña cloth to the East India Marine Society Museum, one of the originating collections of the current Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts (fig. 1).1 Piña cloth is fabric woven out of the finest fibers of pineapple leaves, creating a soft, sheer, and fine material like that of a cotton muslin. A description written directly on this fabric makes note of this material knowledge and leaves a trace of the cloth’s collection history. Though now significantly faded, it reads: “4182 / Made of the fibers of the Pine Apple at Manilla [sic] by the natives” (fig. 2). Rather than an imported good brought back for consumers in the United States, this cloth was categorized under what the Society bylaws termed “articles of curiosity.”2 This language was specific to the Society’s mission to build a scientific collection, in which it charged captains and supercargoes to bring back objects from their travels overseas for the Society’s museum. Applied here, the cloth was designated for building scientific knowledge through early museum practice in the US.

Compared to other objects acquired by the East India Marine Society Museum, Knapp’s piña cloth was unusual. Some merchants at the time did not know the original use and function of the items that they collected. For them and for the viewers who would later see these items on display, the various objects were merely viewed as representations of their respective cultures or of the exchanges that had taken place overseas.3 However, Captain J. J. Knapp was knowledgeable about his cloth, particularly when it came to the fabric’s composition. While seemingly a minute detail—especially given the ghost-like remnants of the cloth’s description—Knapp’s correct identification of the fabric’s pineapple leaf material is rare and exceptional. Due to its material similarity to silk, fine cotton, and linen, piña has often eluded consumers and museum practitioners both then and now.4 Furthermore, while some items in the museum’s founding collection were removed from their original ritual or spiritual environments, because piña did not have a ceremonial function in the Philippines, Knapp’s cloth did not lose any sort of sacred meaning through its acquisition. For the purposes of building the growing collection at the East India Marine Society Museum, Knapp’s knowledge of the cloth was accurate and sufficient.

However, as a small piece of cloth now in the United States, Knapp’s piña was cut from a larger physical and cultural fabric that was left unwritten in Knapp’s description, one that wove together the fabric’s craft and sartorial significance in the Philippines. In the archipelago, the cloth would have moved between the hands of makers and consumers across multiple islands. The first step of production took place on the island of Panay, where artisans worked to extract, process, hand-knot, and weave pineapple leaf fibers. The woven fabric would then travel north to Manila, the present-day capital of the Philippines, and its surrounding regions, where bordadoras (embroiderers) and costureras (seamstresses) decorated and fashioned the cloth into outfits such as the men’s barong tagalog and women’s baro’t saya. As one of the finest fabrics used in these traditional garments, piña clothed the elite echelons of Manila society. The fabric’s translucence and intricate embroidery came to symbolize wealth and a cosmopolitanism that was affordable to only a few. Cut from this cultural fabric, Knapp’s cloth captured both this interisland manufacture as well as the material’s meaning within Philippine fashion.

Reading Knapp’s description and beyond it, this essay unpacks not only the dynamic world of Philippine piña craft and fashion but also the fabric’s inclusion within the founding collection of the East Indian Marine Society Museum. As a textile fragment, the cloth’s very pineapple leaf material remains as an archive of its weaving methods and sartorial culture in the Philippines during the early nineteenth century. At the same time, the fragment is evidence of its significance as an object for scientific inquiry within the East India Marine Society Museum collection, a project that simultaneously projected a global citizenship for a young nation like the United States. Having arrived in the US a decade after the last galleon sailed the Manila–Acapulco trade, this example of piña at the present-day Peabody Essex Museum highlights a new facet of these transpacific crossings. While the Manila Galleon trade might have ended, transpacific exchange continued in new ways with new actors. For Salem, this exchange contributed to a cross-cultural intersection where art, trade, and scientific exploration contributed to early American museum practice at the East Indian Marine Society Museum.5

Nineteenth-Century Philippine Piña Craft and Fashion

Though now a plain-woven, square-cut piece of cloth, Knapp’s piña fabric had once lived in the vibrant world of piña craft and fashion in the Philippines. Far from the static display at the East India Marine Society Museum, Knapp’s cloth embodies a larger and more dynamic context within the textile tradition and cosmopolitan culture of the Philippines during the nineteenth century.

Yet, this dynamic context of piña fabric begins not in the Philippines but in South America. Before discussing piña craft and fashion, it is important to note that the pineapple plant itself is not native to the Philippines. The exact origin story of how the pineapple arrived in the Philippines is shrouded in myth, but most scholars believe that Ferdinand Magellan’s voyages brought the fruit from South America and introduced it to Philippine soil shortly after landing in the Visayan region in 1521.6 As pineapples proliferated in he tropical Philippine landscape, weavers adapted the techniques of creating native banana leaf fabric, or abaca, to producing woven cloth with this new pineapple leaf material. In particular, makers used the method of hand-knotting abaca fibers to make thread for producing piña thread as well.7 By the early nineteenth century, Spanish friar and botanist Manuel Blanco noted this weaving tradition in his botanical text Flora de Filipinas (1837), which is still considered a foundational treatise for Philippine botany. In his entry on the Bromelia ananas species, he recorded that the Native indios made shirts of remarkable delicacy with the fine threads drawn from pineapple leaves.8 Measuring the visual impact of the transpacific crossing of piña requires considering first the transpacific crossing of the pineapple. Even for a cloth closely associated with Filipino culture, Knapp’s fabric must be understood as a product of not just one transpacific crossing but two: the first from South America to the Philippines and the second from the Philippines to the United States.

Although Knapp had written “Manilla” on his fabric, piña production took place and continues to take place on Panay Island, located south of Manila on the western side of the Visayan region. When weavers created Knapp’s cloth during the nineteenth century, centers for piña manufacture existed in Iloilo, a province located in southeast Panay.9 Today, piña is largely woven in the northern portion of the island in the province of Aklan, where the technique remains a cottage industry traditionally practiced by women. While there have been a few technological changes in tools involved in the craft, much of scholars’ and contemporary weavers’ knowledge of historic processes draws from present-day practices.10

The first step in producing Knapp’s piña cloth was harvesting pineapple leaves, which makers then scraped to extract the leaf fiber for the fabric’s thread. The specific pineapple variety used for piña is the Red Spanish pineapple. According to weavers, this pineapple yields stronger fibers than other varieties. The leaves that the artisans harvested came not from the crown of the pineapple but from the bush where the fruit grows. Each leaf measures around a meter long. Once makers gathered the amount of leaves that they planned to scrape for the day, two rounds of leaf scraping ensued to extract two kinds of piña fiber. First, using a sanded-down porcelain plate shard, the leaf-scraper would begin to scrape the epidermis of the pineapple leaf (fig. 3).11 The scraper would remove just enough to reveal the first layer of piña fibers, called the washed-out fiber. The maker would extract these fibers by pulling them up and off the leaf by hand.

For the second round, the scraper would take a coconut shell—also sanded down—and begin scraping the leaf where she had just extracted the washed-out fiber (fig. 4). Once the leaf was thin enough, the maker would pull the second fiber from the back of the leaf, also by hand. This fiber, called liniwan, was the finer of the two. Today, piña textiles are often made with both the coarser washed-out fiber and the liniwan fiber. However, during the nineteenth century, all piña textiles were made only with the finer liniwan fiber.12 Knapp’s piña cloth was most likely woven with liniwan fiber, which is evident in the delicate and translucent materiality of its fabric.

After extracting and cleaning the piña fibers, artisans made piña thread by tying each individual fiber from end to end, resulting in one continuous filament (fig. 5). As previously discussed, piña weavers adapted this technique of hand-knotting fibers from making banana-leaf threads, which were also created by the tying of individual fibers together. Hand-knotting was not limited to preparing piña thread, however. Due to the delicate nature of the fiber, threads often broke as weavers began to prepare the warp or began to weave on the loom. To fix these breakages, the weaver would go back to the broken threads and reconnect the fibers by tying them together. Piña fabrics like Knapp’s cloth display this process of hand-knotting and rehand-knotting. Under magnification, small knots appear throughout the piña fabric, bearing witness to the unique quality of piña thread and the hand-knotting technique necessary to accommodate the fine material (fig. 6). As one can imagine, the process of hand-knotting fibers, both to make and to fix threads, requires great patience and a deft hand.

Once hand-knotters finished creating piña thread, they supplied it to local weavers. Like most weaving traditions, weaving piña began with preparing the warp threads and weft threads. Preparing piña warp meant calculating the length of warp thread that the weaver needed for the desired length and width of the intended fabric. To calculate these measurements, the artisan would wind the hand-knotted piña thread around a cylindrical warp frame, whose wooden spokes marked different points of measurement to help the weaver keep count of the amount of warp threads she had wound (fig. 7). Preparing piña weft required a different process. Taking the hand-knotted piña, the weaver would use a spindle to wind thread around a bobbin. Afterward, she placed the bobbin into a shuttle, which she would then use for weaving (fig. 8). Once the weaver calculated the warp and dressed the floor loom, she began to weave (fig. 9). Most piña fabrics display a plain-weave structure or a variation of one.13 Knapp’s cloth, for instance, displays a plain-weave structure, where one weft thread is woven over one warp thread, resulting in a soft and diaphanous fabric.

The woven piña cloth could go to several textile distribution points after its completion. Within the island of Panay, vendors could sell piña along with other textiles at local, open-air marketplaces. Here, vendors ranged from the local weaver who sold her own products to the entrepreneurial sinamayera, or textile vendor, who sold the products of several weavers and embroiderers. Leaving Panay, ships from Manila transported these woven fabrics from the port of Iloilo back to the capital, where sinamayeras in different districts sold the piña cloth. These markets in Manila often drew in textiles from a variety of provinces, where piña was sold alongside textiles from northern provinces like those in the Ilocos region. Furthermore, as it had been during the height of the Manila–Acapulco trade, Manila remained as the archipelago’s main entrepôt through which foreign merchants could access the Philippine market. Rather than describing where the cloth was woven, then, Knapp’s description of “Manilla” points to the location where he, and most foreign consumers, acquired finished piña fabric.14

Knapp had collected his textile as an undecorated fabric, but had the cloth remained in the Philippines, a textile vendor could have taken the full piña yardage to a nearby bordadora for further embellishment. In the hands of the bordadora, plain piña fabric became a canvas for elegant florals, vines, and geometric patterns (fig. 10). Similar to piña weaving, many of the needlework techniques have remained in use since the nineteenth century.15 During the nineteenth century, these historic embroidery centers were located in various Manila neighborhoods, such as Ermita, Malate, Santa Ana, Tondo, and Paco.16 First, the bordadora would directly embroider on the cloth. This technique allowed her to create the beautiful, free-flowing designs typically seen on piña. The next step was bakbak, or drawn threadwork, in which the bordadora pulled threads from the woven cloth to open the plain weave structure. The result is a gridlike fabric. Lastly, the bordadora would embroider other designs in these open spaces with a technique called calado, or open threadwork. Here, the bordadora would be able to return to decorating with organic lines and forms, and these designs are often in repeating patterns as dictated by the grid drawn by the bakbak of the previous step. Although Knapp’s cloth did not feature any of these embroidered designs, piña fabrics operated within an ecosystem of craft that connected weaving and needlework across multiple islands.

After the cloth was embroidered—or if costumers wanted to keep their fabric undecorated—consumers would have purchased the original yardage and hired a costurera to make clothing. During the nineteenth century, the sartorial culture of the lowland Philippine region was such that the value of a garment was attributed to the material of the clothing rather than the silhouette. Due to the great labor involved in weaving piña, very few could afford to buy the fabric, and piña garments were usually reserved only for special occasions. As a result, piña mostly clothed the elite men and women of Manila, conveying a sense of urbanidad, or an attitude of fashionable, urban refinement.17

For women’s fashion, this economic hierarchy of material was especially apparent as the outfits for women were the same across every socioeconomic class. During the nineteenth century, Filipino women wore the baro’t saya, which consisted of a loose, cropped blouse, called the baro, and a saya, or skirt. Sometimes, women could wear a pañuelo (shawl) over their baro and a tapis (overskirt) that would be wrapped around their saya. The saya and tapis were usually made with thick, dark material, but the baro could range in materials from abaca and cotton to jusi and piña. Nevertheless, while the outfits’ basic silhouettes were the same, the baro that was woven with piña was more expensive, which made it more luxurious than the baro woven with other materials. In the watercolor tipos del pais, or “country types,” paintings created by Damián Domingo (1796–1834), this shift is evident in the blue, opaque fabric of the India Ollera de Pasig’s baro versus the embroidered, translucent baro, pañuelo, and head covering of the Mistisa de Manila (figs. 11 and 12).

Men’s fashion featured a greater variety of silhouettes and therefore depended less on this hierarchy of material to signify the socioeconomic status of the wearer. Among these outfits was the barong mahaba, a long, collared shirt that men wore untucked (fig. 13). Most men on a day-to-day basis, however, wore more simple silhouettes, such as the man featured in Domingo’s Indio de Yloco (fig. 14). Set against this Philippine cultural context, Knapp’s fragment physically and figuratively represents only a piece of this textile and fashion tradition, one whose cultural meaning pulled from botanical history, craft knowledge, and sartorial value.18

Piña in Salem—Mercantile and Institutional Knowledge of Piña

However, Knapp’s cloth did not make it into the barong mahaba or baro’t saya of a Manila man or woman. Cut from its larger fabric, Knapp’s cloth instead traveled from the Philippines to Salem during a moment of economic transition. After the British invaded Manila in the 1760s, Spanish economic control over the Philippine colony weakened, resulting in the gradual cessation of the Manila Galleon trade beginning in 1810 until its last trip in 1815. Trade soon began to open to other foreign merchants outside of Spain, like merchants from the United States.19 Within the Philippines, beginning in 1778, General-Governor José de Basco y Vargas looked to domestic agriculture to supply cash crops for export as he foresaw the end to an economy dependent on the Manila Galleon. This plan for agricultural development coincided with an upsurge in local textile production, which utilized the new crops resulting from the general-governor’s program.20 Knapp’s arrival to the Philippines and acquisition of piña was a point of convergence in the archipelago’s history. The captain had set foot in Manila not only as its ports opened to merchants like him but also during a time when textiles like his piña cloth were the country’s priority for economic development.

As an item categorized under “articles of curiosity,” this object’s classification is distinct from the return cargo that East India Marine Society members brought back as import goods. From the Philippines, Salem merchants brought back indigo, which supplied the growing New England dyeing industry, as well as sugar.21 Abaca, or what was known as Manila hemp, later entered the market as a fiber popularly used for rope.22 In Salem, advertisements for Manila hemp cordage appear in the Salem Gazette into the 1820s.23 Although Knapp’s piña cloth traveled on the same return trip as these other products, the fabric, as an article of curiosity, was separate from the items that traveled as import goods.

Instead, Knapp’s piña cloth gives image to a different material culture in the United States during the 1820s. With the rise of early-nineteenth-century museums in New England and the mid-Atlantic, objects of scientific inquiry were collected from overseas trading ventures in addition to the imported goods sold to the public. Born from eighteenth-century European curiosity cabinets that housed natural and ethnographic objects, institutions like the East India Marine Society Museum fostered this spirit of discovery through active collecting practices. In a similar expression as the cabinet of curiosity, the pursuit for global objects during the early nineteenth century was tied to larger formulations of American national character, one that took shape in relation to the young nation’s citizenship in the world. As a port city with two active marine societies, Salem was uniquely positioned to project this identity as American traders went out and foreign goods entered, fortifying the nation’s connection to the seas and lands beyond it. Collecting articles of curiosity like Knapp’s piña thus served a dual purpose of advancing scientific knowledge as an implicit declaration of national standing.24

As a museum founded and maintained by its members, the East India Marine Society charged both the mariners and its institution with this mission for scientific advancement, conflating both mariner and institutional knowledge of these objects. The traders who had set out from Salem were the first individuals through which knowledge of these items passed. Not only was this expectation clearly stated in the Society’s bylaws, but the journals that each ship was expected to keep also gave detailed instructions regarding object collection. At the tail end of several paragraphs that instruct the daily recording of wind quality, latitude, longitude, and distance traveled, the directions conclude with criteria for object collection:

There should be collected for the Museum, specimens of various kinds of vegetable substances, earths, minerals, ores, metals, volcanic substances, &c. There should also be preserved (according to the directions hereafter given) such parts of birds, insects, fish, &c. as serve most easily to distinguish them. . . . Inquiry should be made for any remarkable books in use among any of the eastern nations, with their subjects, dates and titles. Articles of the dress and ornaments of any nation, with the images and objects of religious devotion, should be procured.25

For mariners like Captain J. J. Knapp, this commission translated into an experiential knowledge of the objects. As men who had set foot in these distant isles and countries, even if for a moment compared to the months spent at sea, East India Marine Society members collected these materials through a direct experience that most did not have of the lands and societies in which these objects originated. In other words, unlike the many who mistook fabrics like cotton or silk as piña, and vice versa, Knapp knew that his cloth was made from pineapple leaf fibers because he had seen the fabric during his time in Manila and was informed of its material.

However, this experiential knowledge must be qualified, as it was not the same as that possessed by those who made and wore piña. For one, though Knapp had physically been in the Philippines, his vocation was not one that allowed him to stay in one place for too long. Unlike the expatriate who resided in a given location for several years, captains and supercargoes spent more time on the ocean than at their destinations.26 As a result, his experiential knowledge was limited to what he could learn about piña from local informants during his short stay in one location. Furthermore, it is also possible that Knapp might have learned more than what he shared with the East India Marine Society. The brief record that made it onto the cloth and into the East India Marine Society catalog might be more reflective of cataloging convention rather than Knapp’s complete understanding of the material. Nevertheless, while Knapp might have learned that the fabric was indeed made with pineapple leaf fibers, his knowledge did not extend beyond what he saw and heard during his time in Manila. As a mariner, Knapp received an incomplete knowledge of piña cloth, returning to Salem unaware of where the cloth was woven and the purposes for which it was used.

Nevertheless, this partial understanding of piña fulfilled the scientific inquiry requested by the East India Marine Society, and it was this object knowledge that became institutional through Knapp’s donation of the cloth to the museum. In the 1831 object catalog, the description written on Knapp’s piña bore more empirical language. Rather than simply “Made of the fibers of the Pine Apple,” as was written on the cloth, Knapp’s piña became a “Specimen of Cloth manufactured from the fibres of the Pine Apple, from Manilla.”27 While the language of the description alone evokes the scientific meaning that Knapp’s cloth had taken on, its context within the rest of the museum’s collection of Philippine objects emphasizes this transformation. Several other objects from the Philippines were labeled as specimens, such as a volcanic pitchstone and ammonite from Luzon, the northern island region where Manila is located.28 Many items were not given the descriptor “specimen,” but they did not deviate too far in nature from objects like the pitchstone and ammonite. Examples include a Muraena fish, iron ore, pearl nautilus cups, and a species of pigeon called Columba cruenta.29 There were a few objects that might have been classified as more cultural than natural, such as a pair of women’s slippers, swords, and cigars, so it is possible that Knapp’s cloth may have been understood as examples of both Philippine culture and natural history.30 Regardless, by the time of its acquisition, piña’s material was stripped of its associations with early histories of craft and cosmopolitan fashion in the Philippines. In the hands of the institution, piña, in its partial understanding and scientific use, along with the other Philippine objects in the museum’s collection, became a material metonym for the Philippines, filling the museum’s metaphorical display case of global knowledge. Cut from the world, Knapp’s cloth remains an archive of the world, weaving together multiple histories and cultural meanings in its pineapple leaf materiality.

Notes

-

At the Peabody Essex Museum, I am grateful to Karina Corrigan and George Schwartz for access to the museum’s piña collection. ↩︎

-

East-India Marine Society of Salem, The East-India Marine Society of Salem (Salem Press, Palfray, Ives, Foote & Brown, 1831), 11, https://archive.org/details/eastindiamarines00east/page/n3/mode/2up. The thirteenth article states specifically that “members shall collect such useful publications, or articles of curiosity, as they think will be acceptable to the Society, either as donations therefore, or to be held in their own private right for the temporary use of the Society, under such terms may be agreed on with the President and Committee.” ↩︎

-

George H. Schwartz, Collecting the Globe: The Salem East India Marine Society Museum (University of Massachusetts Press, 2020), 44–45. ↩︎

-

See Abigail Lua, “Interrogating Translucence: Clarifying Philippine Piña Materiality” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 2023), 1–13. ↩︎

-

While trade between the Philippines and Salem was frequent during this period, scholarship on the exchanges between Manila and New England is relatively new. See Florina Capistrano-Baker, “Beyond Hemp: The Manila–Salem Trade, 1796–1858,” in Global Trade and Visual Arts in Federal New England, ed. Patricia Johnston and Caroline Frank (University of New Hampshire Press, 2014), 251–64. See also Benito Legarda Jr.’s and Capistrano-Baker’s essays in Transpacific Engagements: Trade, Translation, and Visual Culture of Entangled Empires (1565–1898), ed. Florina H. Capistrano-Baker and Meha Priyadarshini (Ayala Foundation, Inc., Getty Research Institute, and Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, 2020), 247–67. ↩︎

-

Lourdes R. Montinola, Piña (Amon Foundation, 1991), 26–27. Montinola’s volume continues to be the authority for most scholarship on the pineapple’s history in the Philippines. Here, she writes of different pathways that the pineapple could have taken in the hands of fifteenth-century Portuguese and Spanish explorers. Elena Phipps cites other sources in her essay on the international trade of silk, cotton, banana fiber, and piña textiles, but these sources also look primarily to Montinola’s volume for the history of the pineapple in the Philippines. With the exception of Antonio Pigafetta’s text from 1521, Montinola’s evidence draws mostly from twentieth-century US sources. A deeper study of the pinapple’s botanical history would enrich future scholarship on piña cloth. Elena Phipps, “Silk, Cotton, Wild Banana, and Piña: Luxury Cloth and Their Materials—Connecting Worlds,” in Transpacific Engagements, 181–95; Luís Mendonça de Carvalho, Francisca Maria Fernandes, and Stephanie Zabel, “The Collection of Pineapple Fibers—Ananas comosus (Bromeliaceae)—at the Harvard University Herbaria,” Harvard Papers in Botany 14, no. 2 (2009): 105–09, https://doi.org/10.3100/025.014.0202. ↩︎

-

Most bast and leaf fibers within the Asian-Pacific context require hand-knotting to create thread. Roy W. Hamilton and B. Lynne Milgram, ed., Material Choices: Refashioning Bast and Leaf Fibers in Asia and the Pacific (Fowler Museum, 2007), 34. ↩︎

-

In the original Spanish: De las hojas de estas plantas sacan los indios hilos finisimos, de los cuales hacen camisas de una delicadeza portentosa. The term indios reflects the racial taxonomical language of the Spanish colonial period. Manuel Blanco, Flora de Filipinas: Segun el sistema sexual de Linneo (Imprenta de Santo Thomas, 1837), 231. ↩︎

-

See Henry F. Funtecha, “Iloilo’s Weaving Industry During the 19th Century,” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 26, no. 1/2 (1998): 81–88. ↩︎

-

See Montinola, Piña; and Lua, “Interrogating Translucence.” Montinola, for instance, documents the contemporary techniques of weaving piña in her monograph, explaining the endurance of these processes into the twentieth century. In 2022, I was also able to visit these piña weaving communities to learn about the material and their craft. In particular, I thank the weavers of Dela Cruz House of Piña, Raquel’s Piña Cloth Products, and La Herminia for their generosity in time and expertise. I also thank Anna India Dela Cruz Legaspi. I draw from this fieldwork for my discussion of Knapp’s cloth. ↩︎

-

A note on the technological continuity of piña production is important here. Before my fieldwork, I was suspicious of many publications’ assumption that the tools and processes of making piña remained unchanged. However, as I met with artisans and observed their craft, the nuances between change and continuity became more evident. While there are certainly a few processes that are now mechanized for greater efficiency, the delicate nature of piña fiber has mostly resisted the use of other tools that might damage the material. See Lua, “Interrogating Translucence,” 25–26. ↩︎

-

Carlos Eliserio, in conversation with the author, July 12, 2022; Montinola, Piña, 53. The washed-out fibers were used to make objects like ropes or the hair of religious icons. In Aklan, the washed-out fibers would be used specifically for Ati-Atihan costumes, which are the costumes worn for the annual Ati-Atihan festival in Kalibo, Aklan. ↩︎

-

In addition to a plain-weave structure, weavers also wove a more open plain-weave structure called rengue. Rengue patterns feature a more open, gridlike weave structure where one warp thread and one weft thread cross each grid square. See Lua, “Interrogating Translucence,” 40. ↩︎

-

Stephanie Coo, Clothing the Colony: Nineteenth-Century Philippine Sartorial Culture, 1820–1896 (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2019), 72–83. ↩︎

-

The following embroidery techniques were observed and taught to me during a visit to the embroidery centers in Taal, Batangas, where they actively embroider nipis garments like piña. ↩︎

-

Coo, Clothing the Colony, 80. See also Maria Luisa Camagay, Working Women of Manila in the 19th Century (University of the Philippines Press, 1995); Patricia Justiniani McReynolds, “The Embroidery of Luzon and the Visayas,” Arts of Asia 10 (January 1980): 128–33; Marlene Ramos, “The Filipina Bordadoras and the Emergence of Fine European-Style Embroidery Tradition in Colonial Philippines, 19th to Early-20th Centuries” (master’s thesis, Mount Saint Vincent University, 2016). In addition to their current focus on the embroidery tradition in Lumban, Laguna, these authors have written about the beginnings and development of embroidery in Manila beaterios (convent schools) and asilos (orphanages). ↩︎

-

Coo, Clothing the Colony, 30–31, 240. ↩︎

-

In using tipos del pais images to explain the sartorial distinctions in nineteenth-century Philippine lowland fashion, I want to acknowledge the voyeurism that might be inherent in this genre of painting. Tipos del pais, which are paintings that depict the different attire across socioeconomic class and race, were products made as souvenirs for international visitors to Manila. As such, these images might not capture the nuanced and lived connections between cloth, fashion, socioeconomic class, and race. ↩︎

-

Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, second edition (Rowman & Littlefield, 2005), 75–76. ↩︎

-

Coo, Clothing the Colony, 64. ↩︎

-

Nathaniel Bowditch, Mary C. McHale, and Thomas R. McHale, Early American-Philippine Trade: The Journal of Nathaniel Bowditch in Manila, 1796 (Yale University, Southeast Asia Studies, 1962), 21. ↩︎

-

See Elizabeth Potter Sievert, The Story of Abaca: Manila Hemp’s Transformation from Textile to Marine Cordage and Specialty Paper (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2009). ↩︎

-

Salem Gazette, June 22, 1824. ↩︎

-

Schwartz, Collecting the Globe, 17, 45. ↩︎

-

Printed Journal Directions from the East India Marine Society of Salem in Joseph J. Knapp Jr., Joseph J. Knapp, Jr.'s journal in the Phoenix (Brig), 1823–1824, MH 88, vol. 10, no. 87, 503. Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Rowley, Massachusetts, https://archive.org/details/mh88v10n87/. ↩︎

-

Dane A. Morrison, True Yankees: The South Seas and the Discovery of American Identity (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), 138. ↩︎

-

The East-India Marine Society of Salem, 173. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 66, 69. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 87, 106, 129, 139, 173. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 43, 52, 69, 90, 94. ↩︎