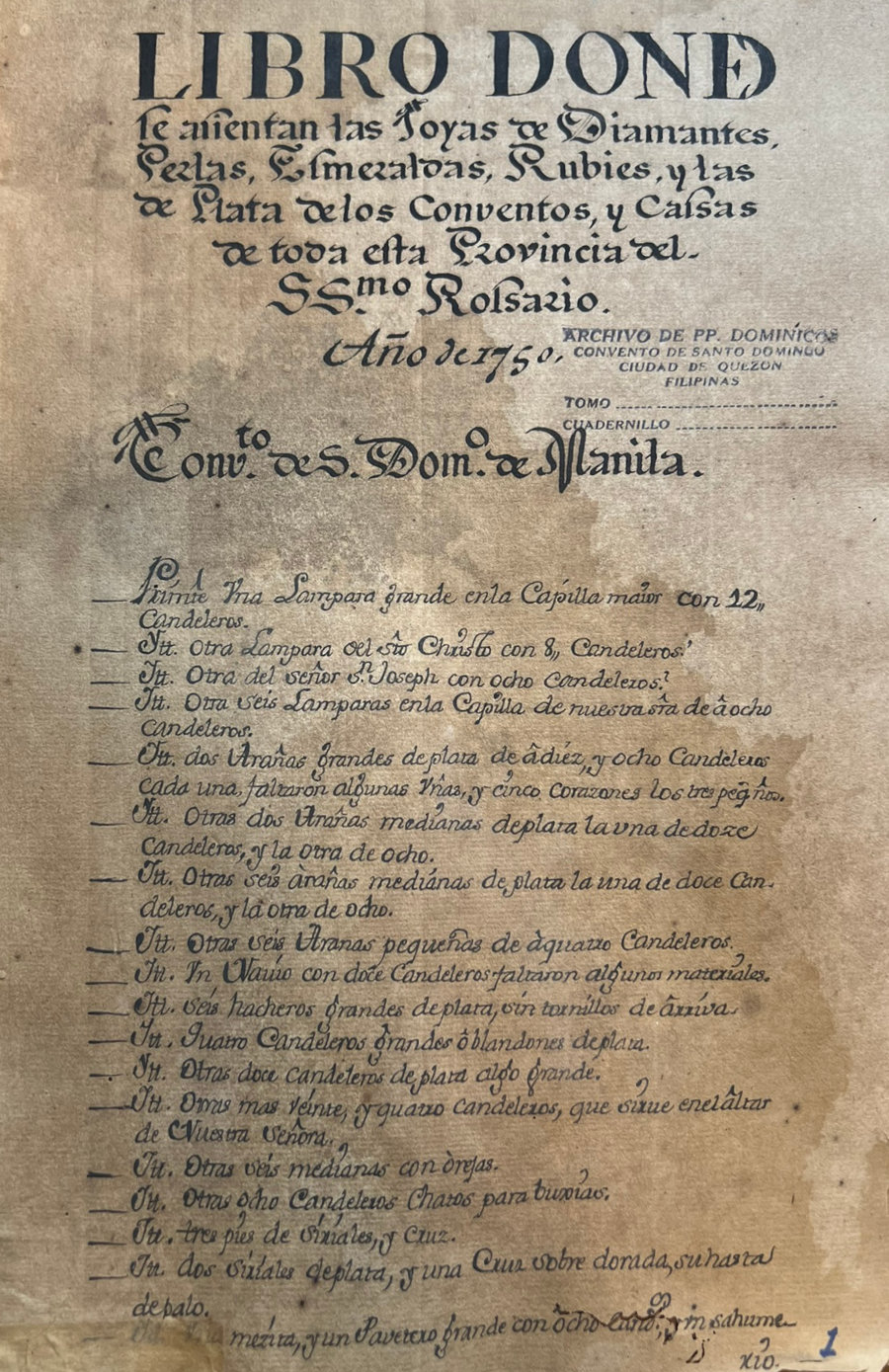

In 1750, the Dominican Order in the Philippines made an inventory of the many alhajas (religious ornaments) and jewels found in its convent, beaterio, college, and the numerous provincial churches spread across what was then known as the Province of the Holy Rosary (fig. 1).1 The inventory extends over more than 150 folios and details the profusion of liturgical silver, religious statuary, and jewelry encrusted with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, sapphires, topazes, and pearls found in these Dominican institutions. Many of the pages are left blank or only partly filled in anticipation of future pious donations, bequests, and purchases that would arrive in coming years to further adorn altarpieces and enhance the Eucharistic experience. While never as wealthy as its Augustinian counterparts, the convent of St. Dominic had among its riches twenty-five lamps and chandeliers, nearly sixty candlesticks, nine chalices, four altar frontals, and eleven crucifixes all wrought in silver and silver-gilt. The jewelry alone went into the hundreds of items. So where did this impressive store of treasure originate?

While a significant thread of research in the last few decades has considered the flow of silver into the Philippines, it has focused on the prodigious quantities of coins mined and minted in Mexico or Potosí that found their way into Chinese coffers.2 Little has been conducted on the flow of finished silver goods into Manila, nor on local facture in the Philippines, which had a rich tradition of Indigenous goldsmithing and was later home to sangley (Chinese) silversmiths. This, in part, results from the paucity of surviving objects: War, natural disasters, and the vagaries of time have resulted in a small number of colonial art objects in all media—let alone silver, which is both desirable and fungible. During the British occupation of Manila during the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), for example, the defending governor issued a mandate to collect and bury silver ornaments from religious institutions to prevent them from falling into the hands of the invading navy, which would soon go on to capture the silver cache onboard the galleon Santísima Trinidad.3 These measures were limited in their success; in October 1762, the British sacked the Dominican church, where they not only looted dozens of silver vessels but also the abundant silver adorning statues like Our Lady of the Rosary, known as La Naval, including her rostrillo (halo or sunburst encircling the face) and gem-studded crown. Not content to simply steal, they desecrated the image, shattering the glass that protected her, cutting off her ivory head and throwing it to the floor, rending her vestments to shreds, and severing the limbs of the Christ Child in her arms. As they rampaged through Manila’s churches, British troops dismantled silver reliquaries, burned nativity scenes, cast the Eucharistic host to the ground, and tied clerical stoles to their horses’ tails.4 Crucially, the 1750 inventory allows us to see a snapshot of the order’s silver before these depredations and the equally devastating losses that would come with the Second World War.5

Despite the rapacity with which it was sought after by Spain’s trading partners and political enemies alike, silver objects are less desirable to modern collectors of Filipinana than locally produced ivories and wooden santos. Only two large public collections of silver can be viewed in Manila today: those of the San Agustin and Intramuros museums. Silver maintains a generally fusty reputation. As Helen Hills observes in her work on Neapolitan silver, “Scholarship and gallery displays are overwhelmingly connoisseurial, drily technical, narrowly specialist, and aridly drained of political engagement,” which belies the complex relationship between the cruelty of silver’s extraction and its exalted position as a substance that “bestowed and conveyed immaculacy and polished sophistication.”6 And yet, silver was not simply the fulcrum of global maritime trade but the very stuff of the sacred. On both sides of the Pacific, it was the preferred material for liturgical objects, saints’ reliquaries, and votive offerings. It was the substance from which the infants of Lal-lo (Cagayan) made their first contact with the sacred through the application of holy water from a silver bernegal (drinking vessel) pressed into service as a baptismal shell; it was the same material used to fashion the spectacular, white sapphire-studded armor of Nuestra Señora de la Consolación in the nineteenth century that aided her in her spiritual mission; it was silver that housed a relic of the True Cross in the church of los Santos Reyes del Parián, where it was hoped that this holy shard might inspire Chinese immigrants to adopt the Catholic faith.

If, to invoke the words of seventeenth-century Spanish chronicler Juan Grau y Monfalcón, Asian goods were “desired and sought by the rest of the world”—what goods were in turn desired by the Spanish, particularly religious communities, living amongst these immediately available and luxurious export goods?7 While the vast majority of cargo on Manila-bound galleons was specie, that is silver reales that could be exchanged for porcelain, silk, ivory, and other fineries, the Spanish also imported gold, olive oil, wine, glass, European clothing and textiles, and art objects. It would seem natural, then, that galleons would also ferry many splendid Mexican and Spanish silverworks bound for Philippine churches: a parallel flow of silver. I had initially hoped to tell a story of silver in Asia as more than a mere commodity and consider artistic influence of the galleon trade that focused on the Philippines rather than Latin America: Mexico in Asia instead of Asia in Mexico. Instead it seems that the landscape is a bit more complicated, especially given the dearth of extant silver objects as well as documents that record them. Despite the difficulty of tracing the course of silver’s importation from abroad, there is a compelling narrative of local creation by sangley artisans to be told.

Silver in the Philippines

Whether imported as finished objects or, as was more common, wrought locally, silver in the Philippines began its life in the bowels of the Cerro Rico in Potosí or the mountainous regions of Mexico. The quantity of silver mined at Potosí in particular was so immense that chroniclers reported that “it was considered easier and cheaper to arm men and shoe horses with silver than with iron.”8 So too did they describe with openmouthed awe the mind-bending splendor to which this Mexican and Bolivian silver was put for local celebrations: formed into cobblestones for viceregal entries and forged into triumphal arches, images of the Virgin, and miniature silver mountains for religious processions.9 And yet, potosino silver was famously extracted through a brutal system of forced labor known as the mita. After extraction, silver ore was locally processed through smelting or amalgamation, assayed, and formed into silver bars or minted into coins.10 It was then transported to various artistic centers where it was worked by plateros who forged it into objects both sacred and profane, from processional crosses and chalices to inkstands and chamber pots. In the process, it lost its association with the cruelty of the extractive process and became associated with both secular refinement and religious majesty.11

When the mendicant orders first came to the Philippines in the sixteenth century, they brought with them from Spain the necessary objects to conduct mass.12 A royal decree promulgated by Philip II in 1579 provisioned each new mission in the Philippines with an “ornament,” chalice, paten, and bell from the royal treasury.13 This basic service would later be augmented by both imported goods from Mexico and Spain and objects forged locally. In the early days of the colony, however, few churches were able to adequately outfit their altars; reports from colonial officials in Manila often lamented the lack of necessary and beautifying orfebrería in the city’s cathedral.14 This was seen as a matter of some urgency; adequate silver was necessary to maintain the dignity of mass, to minister to the faithful, and to convert a new flock.15 Some priests took on the cause of ornamenting provincial churches themselves rather than relying on their orders or the Crown to do so, such as fray Fernando Cabrera, who furnished the church of San Pablo de los Montes (Laguna) with such a surfeit of liturgical silver that it was said to outshine the cathedrals of Spain, and its most exceptional object (a silver tabernacle described below) was subsequently redistributed to the Augustinian convent in Manila a few miles away.16 While the influx of silver coins via the Manila Galleon was significant, the Crown placed limitations on the importation of wrought silver to the colony.17 Private citizens and public officials could submit a formal request to the Crown to import wrought silver and jewels for their personal use.18 Yet private citizens, government and church officials, and institutions imported silver objects from Mexico with regularity, often clandestinely.19 At the time of his death in 1667, the archbishop of Manila, Miguel de Poblete, had some forty-six items of plata labrada (wrought silver) in his possession valued at nearly 4,350 pesos, much of it likely brought from his homeland of Mexico. Among them were sacred objects like chalices and a silver-gilt bishop’s crosier but also luxury goods including a set of coconut cups with silver mounts, a perfumer, and three elaborate fountains.20

As in other colonies, arriving missionaries relied on local artists and artisans to create religious objects for newly constructed Catholic churches. The skill of sangley artisans was more than sufficient to meet this need: So talented were they in replicating European statuary that, by 1590, bishop Domingo de Salazar wrote to Philip II that “soon we shall not even miss those made in Flanders.” Salazar praised the quality of smithing in particular: “Although the silversmiths do not know how to enamel (for enamel is not used in China), in other respects they produce marvelous work in gold and silver. They are so skillful and clever that, as soon as there are any objects made by a Spanish workman, they reproduce it with exactness.”21 While Salazar was mistaken on the use of enamel in China, which had begun in the fourteenth century, his high opinion of sangley silversmiths’ talent was widely shared. Their work was so desirable, in fact, that the tumbaga (an alloy of copper, gold, and silver) choir screen in Mexico City’s cathedral was commissioned from Chinese artisans in Macao in the 1720s, and the Sultan of Jolo (Sulu) requested a sangley silversmith be sent to his court in 1756.22 As commerce with New Spain became more regular at the end of the sixteenth century, imported religious objects were presumably more available, but nevertheless there remained a strong reliance on local manufacture in silver as well as indigenous materials like nacre and wood.

The first wave of Chinese silversmiths came to Manila from the provinces of Fujian and Guangdong, the latter of which became a regional center of silver production in the sixteenth century.23 As with other artisans, they concentrated around the Parián, the market just outside Manila’s walls where Asian goods were bought and sold. Some arrived with skill in smithing, while others likely learned their trade in Manila, which helped them survive in a colony hostile to chinos.24 Later generations of silversmiths would be not only sangley but also Chinese-mestizo and Filipino and likewise received praise for their skill from Spanish commentators—in some cases above sangleys.25 By 1690, there were twenty-four sangley silversmiths working in the Parián, and fifty-seven were active in the city in 1700.26 Unlike their counterparts in Mexico, Manila’s artisans were only nominally organized under a guild system and instead operated through a series of independently run companies and workshops, which numbered forty-eight by midcentury.27

There is also evidence of at least one silversmith who also worked as an ivory carver in the case of Juan de los Santos, a Filipino born in the village of San Pablo de los Montes who served as the sacristan of its church. De los Santos was responsible for a variety of works in Augustinian churches in the early seventeenth century, from gilded retablos to ivory sculptures and elaborate objects wrought in silver. While a perhaps singular example of talent, de los Santos allows us some insight into the relationship between commissioning friars and local artisans. According to the Augustinian chronicler Pedro Andrés de Castro, “He made with his own hands all of the silver ornaments of the church, which were many and good . . . but everything was at the cost, zeal, direction, and care of [the prior] fray Fernando Cabrera,” the silver-loving priest from above.28 It is unlikely that any of these silver objects survives in the San Agustin museum today, as much of the museum’s collection was relocated from churches in Cebu, but Castro’s text provides a sense of its splendor. He describes in great detail a nine-and-a-half-foot-tall, gothic-style silver tower made by de los Santos to hold a gold monstrance, which featured five octagonal tiers with varying orders of columns and was adorned with jewels, bas-reliefs, and figures of the Apostles, Doctors of the Church, and angels. Clearly, silversmiths in Manila were capable of a remarkable degree of sophistication; as Castro noted in his text, in this instance, the “work exceeded the material” (materiam superabat opus).29 As with many of Manila’s most spectacular silver objects, it was seized during the British Occupation, reinforcing the importance of documents like the Dominican inventory and Castro’s chronicle to understand local silver production.

Such grandiose objects were commissioned because silver was a key part of the missionizing effort, beautifying the church space and enticing new converts to Catholicism through its burnished splendor. The ornamentation of the church “heightened the magnificence of the sacred” and moved the pious to meditate on the divine.30 The Jesuit chronicler Pedro Chirino reported that one vicar “embellished [his church] with new ornaments, very rich and curious, such as lamps and silver candlesticks, thereby augmenting the reputation and esteem of our holy religion among those new nations.”31 Laypeople likewise sought to enhance the beauty of the church through pious bequests of silver, thereby participating in the baroque theater of mass. As the Augustinian friar Juan de Medina pointed out, silver made a more attractive bequest for manileños because, unlike textiles, it would not become destroyed by Luzon’s infamous humidity and could simply be polished to renew its former luster.32 And, much as the tarnish could be removed from sacred silver objects through the labor of polishing, so too would the redemptive nature of the sacraments wash away the stain of sin.

Many objects in the Dominican inventory arrived as gifts, often from Manila’s ecclesiastical and secular elite. These were primarily jewels given in offering to statues, such as a large silver star set with nine diamonds placed on the forehead of a statue of Saint Dominic and given by the bishop-elect of Nueva Segovia, Juan de Arrechedera, or several jewels given to religious statues by Juana del Rosario, a Japanese mestiza.33 Other objects—like the small silver ramilletes (stylized vases of flowers) donated by the marquesa doña Rita de Quijano to Our Lady of the Rosary—were intended to enhance the liturgical experience by ornamenting the altar (fig. 2).34 Unlike in Mexico or Peru, no statue paintings survive to show us what these altars might have looked like, but written sources can help to reconstruct their appearance. For example, the devotees of La Naval adorned her altar with more than fifty silver lamps and candlesticks to illuminate her ivory countenance and sumptuous embroidered robes. The governor of Ternate, Pedro de Heredia, was alone responsible for donating two large candlesticks (blandones) valued at over a thousand pesos each, twelve smaller candlesticks (candeleros) at a hundred pesos apiece, and a lamp valued at 1500 pesos.35

It is unclear whether these objects were imported or locally produced, though the latter seems most likely given the availability of local talent and the time and expense of importing finished silver objects from Mexico or Spain. Philippine silver objects lack the hallmarks typically found on their Mexican and Spanish counterparts because they were often made from reworked silver pesos and therefore no royal tax (quinto real) needed to be paid.36 Other scholars attribute the lack of hallmarks to the abundant use of filigree work, which left no room for stamping on its delicate designs.37 Hallmarks indicated not simply the payment of tax but also revealed the maker, the location, the year, and the assayer who gauged the quality of the work. This leaves the objects that do survive today as orphans, unidentified in time, place, or authorship. A silver panel from the Denver Art Museum collection is a good illustration, not readily identifiable as either Mexican or Philippine, though it was acquired in Manila (fig. 3). In the nineteenth century, as the plantation economy increased the wealth of provincial towns, prominent citizens would commission silver altar frontals, which sometimes had their names inscribed on them.38 Inscriptions like these are, other than stylistic attributions, analysis of wooden supports, and scant documentary references, among the only ways to tie works concretely to a geographic origin.39

Unfortunately, but predictably, the Dominican inventory is circumspect on the origins of the silver in its sacristies, with only a few exceptions. In what was then the village of Ermita, now a neighborhood in central Manila, one Padre Bernabe commissioned for the church two heavy silver chandeliers (arañas) weighing nine and a half pounds as well as a silver cross for the altar.40 Across the Pasig river, in the church of los Santos Reyes del Parián, the silver chandeliers illuminating the altar of el Santo Christo del Valle had been sent from Mexico.41 In the seventeenth century, Manila’s once-impoverished cathedral was at last furnished with “a quantity of wrought silver and very rich ornaments and lamps” sent from Guadalajara by archbishop Diego Camacho y Ávila.42 Likewise, some of the surviving works at San Agustin are thought to have been imported from Mexico, including a famous bejeweled gold and enamel chalice from circa 1600—though more recent attributions locate the work to Colombia or the Philippines.43 Unsurprisingly, many attributions are unreliable, like a set of gold cruets at San Agustin whose serpentine handles are said to represent Quetzalcoatl, a Mexica deity.44 In one remarkable example, a Mexican chalice was reworked in Manila and then donated to a parish in Andalucía (fig. 4). The inscription on the base of the chalice states: “To the parish of Mairena del Alcor, by Don Angel Carmona and companions (compañeros), [made] in Acapulco, renewed by another in Manila, 1787.”45 Stylistically, the work resembles Philippine typologies in the undulating curve of its base, the three nodes (or knops) on the stem, and the double cup separated by two rings, which suggests that it was a substantial renovation, perhaps after the original work sustained damage or simply to elaborate the original design.46

Early works by sangley masters were often created using the ysot, or wriggle-work technique, in which a v-shaped chisel or burin incised designs into the silver plate. This was joined in the late seventeenth century by chasing and by repoussé, embossing, casting, and engraving in the eighteenth.47 Stylistically, these works can have an archaizing quality, referencing earlier prototypes of Renaissance, Mannerist, and early Baroque silver. Even Juan de los Santos’s nine-foot silver confection harks back to the high Renaissance in its composition of varying orders of columns.48 Still, Philippine silver would eventually come to adopt rococo designs like the s- and c- scrolls and rocalla that were popularized in eighteenth-century Europe. As María Jesús Sanz has pointed out, many of the surviving objects at San Agustin betray simultaneous influences from Chinese, Spanish, and Mexican silver traditions, which suggests a local authorship.49 So, too, does it bespeak the consistent importation of Mexican and Spanish objects to serve as artistic prototypes, even if these objects have been difficult to trace in the documentary record.

As mentioned, filigree was a technique favored by sangley artisans, though it was also popular in the Americas, Southeast Asia, and India. Filigree and granulation techniques had been used in prehispanic Philippine goldwork, but filigree became increasingly prominent after the arrival of Chinese smiths in the sixteenth century.50 San Agustin’s best surviving examples of the technique are in gold: a palabra or sacra, probably the most spectacular object in the collection, and a pen and heart belonging to a statue of St. Augustine (fig. 5). These latter objects may well be the same ornaments lauded by Castro in his text, where he boasts that they “could shine in Rome and Toledo for their value and workmanship.”51 Examples of filigree work were exported from the Philippines to Spain, Italy, Mexico, and Lima, while others were traded clandestinely to England via Madras (now Chennai).52 They were found not only in private collections but in ecclesiastical and royal settings: Splendid lamps commissioned in the Philippines hung in the Dominican convent in Rome, and filigree objects belonging to a lady’s dressing table (tocador de señora) were displayed in the recently created Real Gabinete de Historia Natural in Madrid alongside other curiosities.53 The exquisite quality of the work was often praised by commentators, one of whom remarked that it had “astonished the Europeans” (pasmado a los Europeos) who beheld it and had quickly been imitated by Italian artisans—though Diego Aduarte insisted they could not achieve the mastery of their Asian counterparts.54 A few examples of sangley filigree work have been identified in Spain, including a monstrance in Caicedo de Yuso, which came at the bequest of the oidor (judge) Francisco de Samaniego, who had been born there and spent much of his career in Manila.55

Silver, including filigree work, was often incorporated into works of ivory, not just as crowns and scepters but as the wings on sets of ivory angels or as silver overlays on the garments of religious statues.56 But this technique was perhaps most famously used in the ivory niños dormidos that rest on elaborate beds trimmed with “trinkets and little pieces of silver.”57 The eighteenth-century niño dormido in the Bangko Sentral collection is the prototypical example (fig. 6). It features design elements that suggest Chinese or sangley authorship, such as phoenixes and gourds wrought in silver and kingfisher feather inlay. Its filigree work is also distinctly Chinese in style, which tended to be smaller and more delicate than contemporary Cuban or Central American examples.58 While these objects have been primarily understood as domestic in use, the Dominican convent had four such statues in its inventory, which noted the Christ Child’s gilt-wood beds dangling with silver, gold, and jewel-embellished pendants.59

Iglesia de los Santos Reyes del Parián

To close with a brief example from this very lengthy inventory, note the church of los Santos Reyes del Parián, founded by the Dominican order in 1617 to minister to the Chinese community, including the many artisans who sold their wares there.60 The original structure was rebuilt repeatedly before the area was demolished in the late eighteenth century, the church along with it. In his chronicle, Diego Aduarte describes the “very well adorned” (muy bien adornada) church with its many edifying images.61 It was home to numerous painted and sculpted depictions of saints and advocations of the Virgin—including Our Lady of Consolation and Our Lady of Biglang Awa—that were adorned with silver bases, rostrillos, and crowns. In one of the lateral altars stood the Santo Christo del Valle that had received the donation of silver lanterns from Mexico.

The church was outfitted with all of the standard objects appropriate to maintain the propriety and dignity of Mass, including silver gradillas (small steps) to display religious images, a tabernacle (sagrario), an altar frontal, a pyx with its case, two monstrances, two chalices, two sets of cruets, a reliquary of the True Cross, a baptismal shell, and multiple palabras. But what is notable about this church is that it is one of the only sections of the inventory that includes reference to the weight or value of the silver objects catalogued. One wonders if this is merely the work of a singular, zealous priest with a scale or a result of the artisan population ministered to in the Parián, with their personal knowledge of the value of wrought silver.62

Many of the silver objects appear to have been made locally by sangley artisans, some directly at the behest of the Chinese Christian community, which remained a tiny minority in Manila. Various objects, including a silver banner for a statue of St. Dominic, were wrought from silver described as “unspendable” (ingastable), which probably meant reserve silver, meaning that the objects had been made in Manila and could be melted down if necessary. Four large candleholders were made jointly from this same unspendable silver as well as from reworked pesos given as pious donations for masses by parishioners. Other objects were commissioned specifically by the sangley community, like a large silver lamp valued at over 240 pesos and funded jointly by the Dominican house, which paid for the labor of the silversmith at a cost of twenty-five pesos.63 These objects tell us that the Chinese converts of Manila took an active role in the beautification of their own church, commissioning a lamp and entrusting a member of their community to create this object as a devotional act. Notably, none of the jewels recorded at the church were given by sangley parishioners, which may suggest that they found platería to be a worthier donation than the jewels often favored by Manila’s peninsulars and creoles.64 The inventory offers limited details—and may even be incomplete, as one folio appears to be missing—but it gives us a glimpse into the relationship that sangley converts had with sacred silver.

Conclusion

Across the archipelago, Philippine churches gleamed with candlelight reflected in polished silver surfaces. Despite clear evidence of their abundance, the origins—and fates—of these objects remain largely obscure. Without extended archival and collections research, it remains difficult to fully trace the history of importation and production of silver in the Philippines. In 1990, Ramon N. Villegas posed future directions for the study of Philippine silver; thirty-five years later, these questions remain largely unanswered.65 For example, too little is known about the role of inter-Asian trade in silverworks; this essay is also guilty of trying to triangulate Philippine silver between the nodes of China, Mexico, and Spain without reference to additional influences from Southeast Asia.

What is clear is that sangley and, to a lesser extent, Indigenous artisans dominated the trade for wrought silver, producing works that were so prized as to be traded across the globe and displayed in exalted spaces from Lima to Rome. Manila’s sangley artisans have been examined primarily as ivory carvers. Attending to their roles as silversmiths helps us better understand not only the kinds of work they produced but the very nature of artistic production in a city where professions were plastic and immigrants looked for economic opportunities wherever they might appear.66

Notes

-

Archivo de la Provincia del Santísimo Rosario (hereafter APSR), Avila, Estante 1, Tomo 164, “Libro donde se asientan las Joyas de Diamantes, Perlas, Esmeraldas, Rubies, y las de Plata de los Conventos, y Casas de toda esta Provincia del Ssmo Rossario, Año de 1750.” ↩︎

-

See Katharine Bjork, “The Link That Kept the Philippines Spanish: Mexican Merchant Interests and the Manila Trade, 1571–1815,” Journal of World History 9, no. 1 (1998): 25–50; Dennis O. Flynn and Arturo Giráldez, “Born with a ‘Silver Spoon’: The Origin of World Trade in 1571,” Journal of World History 6, no. 2 (1995), 201–21; Flynn and Giráldez, “Cycles of Silver: Global Economic Unity Through the Mid-Eighteenth Century,” Journal of World History 13, no. 2 (2002): 391–428. ↩︎

-

Archivo-Biblioteca Provincial Franciscano (ABPF), Fondo: AFIO; Sección A-Manuscritos, Documento: 21/28, “Relación de los sucesos acaecidos en la pasada Guerra de los Yngleses por lo perteneciente solamente al convento de Sta. Clara y sus religiosas en Manila,” 1764, f. 1v–2r. ↩︎

-

Pedro María Jordán de Urriés y Urriés, Marqués de Ayerbe, Sitio y conquista de Manila por los ingleses en 1762 (Ramón Miedes, 1897), 67–68; APSR, Estante 1, Tomo 380, Sección Historia Civil de Filipinas, Tomo 1, doc. 13. “En este mes el día cinco después de doze días de cercada la Ciudad por los Ingleses . . .,” 1762; Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga, Historia de las islas Philipinas (Pedro Argüelles de la Concepción, 1803), 642. ↩︎

-

Frequent losses of silver ornaments also occurred during conflicts with the Muslims in Mindanao. See Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898, 55 vols. (The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1905), 24:117. ↩︎

-

Helen Hills, “Colonial Materiality: Silver’s Alchemy of Trauma and Salvation,” MAVCOR Journal 5, no. 1 (2021): 4, 1. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 27:88. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 17:216. ↩︎

-

Bartolomé Arzáns de Orsúa y Vela, Historia de la villa imperial de Potosí, 3 vols. (Brown University, 1965), 1:95–97, 348–49, 390; Amédée-François Frézier, Relation du voyage de la mer du sud aux côtes du Chily et du Perou, fait pendant les années 1712, 1713 & 1714 (Jean-Geoffroy Nyon, Etienne Ganeau, Jacque Quillau, 1716), 195–96; Irving A. Leonard, ed., Colonial Travelers in Latin America (Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), 142–43. ↩︎

-

Jorge Chapa, “The Creation of Wage Labor in a Colonial Society: Silver Mining in Mexico, 1520–1771,” Berkeley Journal of Sociology 23 (1978): 103. ↩︎

-

Hills, “Colonial Materiality,” 4. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 7:206. ↩︎

-

Archivo General de Indias (hereafter AGI), Seville, Filipinas 339, L.1, f. 156r–156v. ↩︎

-

See Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 10:142–43, 142n12; 20:78–79; 7:70, 142–43. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 9:221. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 23:284. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 17:46–47; AGI Mexico 27, N. 18, f. 4r. ↩︎

-

Cf. AGI Filipinas 348, L. 4, f. 344r; Filipinas 339, L.1, f. 240r. ↩︎

-

AGI Filipinas 96, N. 60. ↩︎

-

Cayetano Sánchez Fuertes, “Biblioteca, pinacoteca, mobiliario y ajuar de Don Miguel de Poblete, arzobispo de Manila,” Archivo Agustiniano 95, no. 213 (2011): 428–32. My thanks to Ronda Kasl for sharing this article with me. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 7:226. ↩︎

-

Manuel Toussaint, La catedral de México y el Sagrario Metropolitano: su historia, su tesoro, su arte (Editorial Porrúa, 1973), 107; AGI Filipinas 199, N. 5. ↩︎

-

Susan I. Eberhard, “Metamorphic Medium: Materializing Silver in Modern China, 1682–1839” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2023), 16; Birgit Tremml-Werner, Spain, China, and Japan in Manila, 1571–1644: Local Comparisons and Global Connections (Amsterdam University Press, 2015), 285n116, 289n143. ↩︎

-

Jessie Park, “Made by Migrants: Southeast Asian Ivories for Local and Global Markets, ca. 1590–1640,” The Art Bulletin 102, no. 4 (2020): 73–75; Tremml-Werner, Spain, 285. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 40:285n331; AGI Filipinas 28, N. 131, f. 970v, 972v. ↩︎

-

AGI Filipinas 202, f. 385v; 435v–436v. ↩︎

-

Joshua Kueh, “The Manila Chinese: Community, Trade, and Empire, c. 1570–c. 1770” (PhD diss., Georgetown University, 2014), 112–13; Pedro Luengo Gutiérrez, “Arte oriental e inquisición en Manila a principios del siglo XVIII,” in La Nao de China, 1565–1815, ed. Salvador Bernabéu Albert (Universidad de Sevilla, 2013), 174–75; AGI Filipinas 562, “Razon Yndividual de los Gremios del Parian de Sangleyes, y consumo anual de cada gremio en el estado presente,” f. 1v. Repeated attempts were made to standardize the creation of gold and silver ornaments (alhajas) in the Philippines and to organize silversmiths into a proper guild. See Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 50:103–04; AGI Filipinas 144 N. 5; Filipinas 95, N. 104; Filipinas 147, N. 2. ↩︎

-

“Trabajó por su mano todas las alhajas de esta iglesia de plata, que eran muchas y buenas . . .; pero todo fué [sic] a costa, a celo, dirección, y cuidado del P. Fr. Fernando Cabrera,” Manuel Merino, “El Convento Agustiniano de San Pablo de Manila,” Missionalia Hispanica 8, no. 22 (1951): 105n49. However, in another of Castro’s manuscripts, he mentions objects at San Pablo de los Montes of silver and gold “made in Canton.” See M. Rasi Roice, “San Pablo de los Montes,” Libertas 4, no. 816 (1902). ↩︎

-

Merino, “El Convento,” 105n49. ↩︎

-

Brian R. Larkin, The Very Nature of God: Baroque Catholicism and Religious Reform in Bourbon Mexico City (University of New Mexico Press, 2010), 77. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 12:221–22. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 23:235. ↩︎

-

APSR, “Libro,” f. 24r. N.B. The document incorrectly notes Arrechedera’s first name as Francisco and his position as archbishop-elect. ↩︎

-

APSR, “Libro,” f. 2v. ↩︎

-

Diego Aduarte, Tomo primero de la historia de la provincia del Santo Rosario de Filipinas, Japon y China (Domingo Gascón, 1693), 34. ↩︎

-

Martin I. Tinio, “Silver,” in Consuming Passions: Philippine Collectibles, ed. Jaime C. Laya (Anvil Publishing, 2003), 229. ↩︎

-

Pedro Luengo, personal communication, November 2024. ↩︎

-

Tinio, “Silver,” 227. ↩︎

-

María Jesús Sanz, “Aspectos de la platería filipina. Entre la influencia española, la mexicana y la oriental,” in El sueño de El Dorado: estudios sobre la plata iberoamericana (siglos XVI-XIX), ed. Jesús Paniagua Pérez, Nuria Salazar Simarro, and Moisés Gámez (Universidad de León; Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2012), 387–88. ↩︎

-

APSR, “Libro,” f. 124r ↩︎

-

APSR, “Libro,” f. 56r. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 37:204. ↩︎

-

Pedro G. Galende and Clifford T. Chua, The Gold and Silver Collection: San Agustin Museum, Intramuros, Manila (National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 2003), 4–5; Clement Onn, Alan Chong, and Benjamin Chiesa, eds., Across the Pacific: Art and the Manila Galleons, exh. cat. (Asian Civilisations Museum, 2024), 43; Sanz, “Aspectos,” 391. ↩︎

-

Galende and Chua, Gold and Silver, 32. ↩︎

-

“A la parroquia de Mairena del Alcor, por Don Ángel Carmona y compañeros, en Acapulco, renóvose en Manila por otro, año de 1787.” ↩︎

-

Sanz, “Aspectos,” 393. ↩︎

-

Martin I. Tinio, Sanctuary Silver, exh. cat. (The Intramuros Administration, 1982), 8. ↩︎

-

Margarita Estella Marcos, “Artes aplicadas y marfiles,” in España y el Pacífico: Legazpi, vol. 2, ed. Leoncio Cabrero Fernández (Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, S.A., 2004), 450. ↩︎

-

Sanz, “Aspectos.” ↩︎

-

See Ramon N. Villegas, Kayamanan: The Philippine Jewelry Tradition (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, 1983), 72–73, 108. ↩︎

-

“Podían lucir en Roma y en Toledo por su valor y por su hechura.” Merino, “El Convento,” 105. ↩︎

-

Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 36:202; Francisco de Echave y Assu, La estrella de Lima convertida en sol sobre sus tres coronas (Verdussen, 1688), 82; Serafin D. Quaison, English “Country Trade” With the Philippines, 1644–1765 (University of the Philippines Press, 1966), 47, 73. ↩︎

-

Aduarte, Tomo primero, 422; Revista de instrucción pública, literatura y ciencias 5, no. 16 (1860), 251; Catálogo de documentos del Real Gabinete de Historia Natural (1752-1786) (C.S.I.C., 1987), 137. ↩︎

-

Echave y Assu, La estrella, 82; Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands, 36:202; Domingo Fernández Navarrete, Tratados históricos, políticos, éticos, y religiosos de la monarquía de China (Imprenta Real, 1676), 57; Aduarte, ibid. ↩︎

-

Ana Ruiz Gutiérrez, “La ruta comercial del Galeón de Manila: El legado artístico de Francisco de Samaniego,” Goya: Revista de Arte 318 (2007): 164–66. A more recent essay by Carmen Heredia Moreno calls this attribution into question. See “Una aproximación a los plateros y a la plata labrada en los autos de bienes de difuntos indianos de la época virreinal,” in Las artes suntuarias al servicio del culto divino. Siglos XVI-XVIII, ed. Laura Illescas et. al. (Universo Barroco Iberoamericano, 2024), 321. ↩︎

-

APSR, “Libro,” f. 1v; illustrated in Regalado Trota Jose and Ramon N. Villegas, eds., Power + Faith + Image: Philippine Art in Ivory from the 16th to the 19th Century, exh. cat. (Ayala Foundation, 2004), 218. ↩︎

-

Will of doña Maria Marquez y Quintos de la Torre, April 12, 1737, quoted in Trota Jose and Villegas, Power, 271. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 162; Pedro Luengo, “Mestizo Musical Iconography: Manila’s Santo Niño Cradle,” Cultural and Social History 16, no. 4 (2019): 13n33. ↩︎

-

APSR “Libro,” f. 2v. ↩︎

-

APSR, “Libro,” f. 56r–58r; AGI Filipinas 652, n. 6, f. 33r–39v. See also Juan Gil, Los chinos en Manila. Siglos XVI y XVII (Centro Cientifico e Cultural de Macau, 2011), 168–74. ↩︎

-

Aduarte, Tomo primero, 467. ↩︎

-

For example, Don Juan Sunco, a sangley silversmith, acted as celador in 1686, ensuring the purity of faith of its congregants. Gil, Los chinos, 173. ↩︎

-

APSR, “Libro,” 56v. ↩︎

-

This is anecdotally supported by a donation of silver religious ornaments made to a church in Binondo by the unnamed brother of the sangley Juan de Vera. Aduarte, Tomo primero, 100. ↩︎

-

Pamanang Pilak: Philippine Domestic Silver, exh. cat. (Ayala Museum, 1990), 22–23. ↩︎

-

AGI, Filipinas 28, N. 131, f. 1016r. ↩︎