On March 3, 1653, a celebrated image of the ecce homo departed Acapulco for Manila on the galleon San Francisco Xavier in the custody of Augustinian Recollect missionaries. Known as the Christ of Humility and Patience, the sculpture, which was venerated in the monastic church of San Nicolás de Tolentino, was destroyed in the bombardment of Manila in 1945 (fig.1). A prewar photograph preserves a blurry record of its appearance, but early written sources vividly describe it as a life-size image of the scourged and humiliated Christ, crowned with thorns and holding a reed scepter (fig. 2).1 Official histories of the Recollects narrate the story of its origin, its translation from Mexico City to Manila, and its festive reception there in mid-October 1653.2 Chronicles and eye-witness reports by members of other religious orders corroborate many details of the sculpture’s history.3 While the documentary and explanatory value of these sources is considerable, they are far from neutral. Recognition of the aims and biases of those who recorded the details amassed in this case study is crucial, not only in the interest of objectivity but because it illuminates attitudes toward the making, use, and mutable resonances of sacred images in movement. The first objective of this investigation is to document the existence of a sculpture sent from New Spain to the Philippines in the mid-seventeenth century and the second is to reconstruct its context to understand how it functioned in the practice of belief under circumstances described by contemporaries as both miserable and calamitous. The analysis of written sources foregrounds the contention that a sacred image made in Mexico City had the capacity to console a divinely castigated community on the other side of the world.

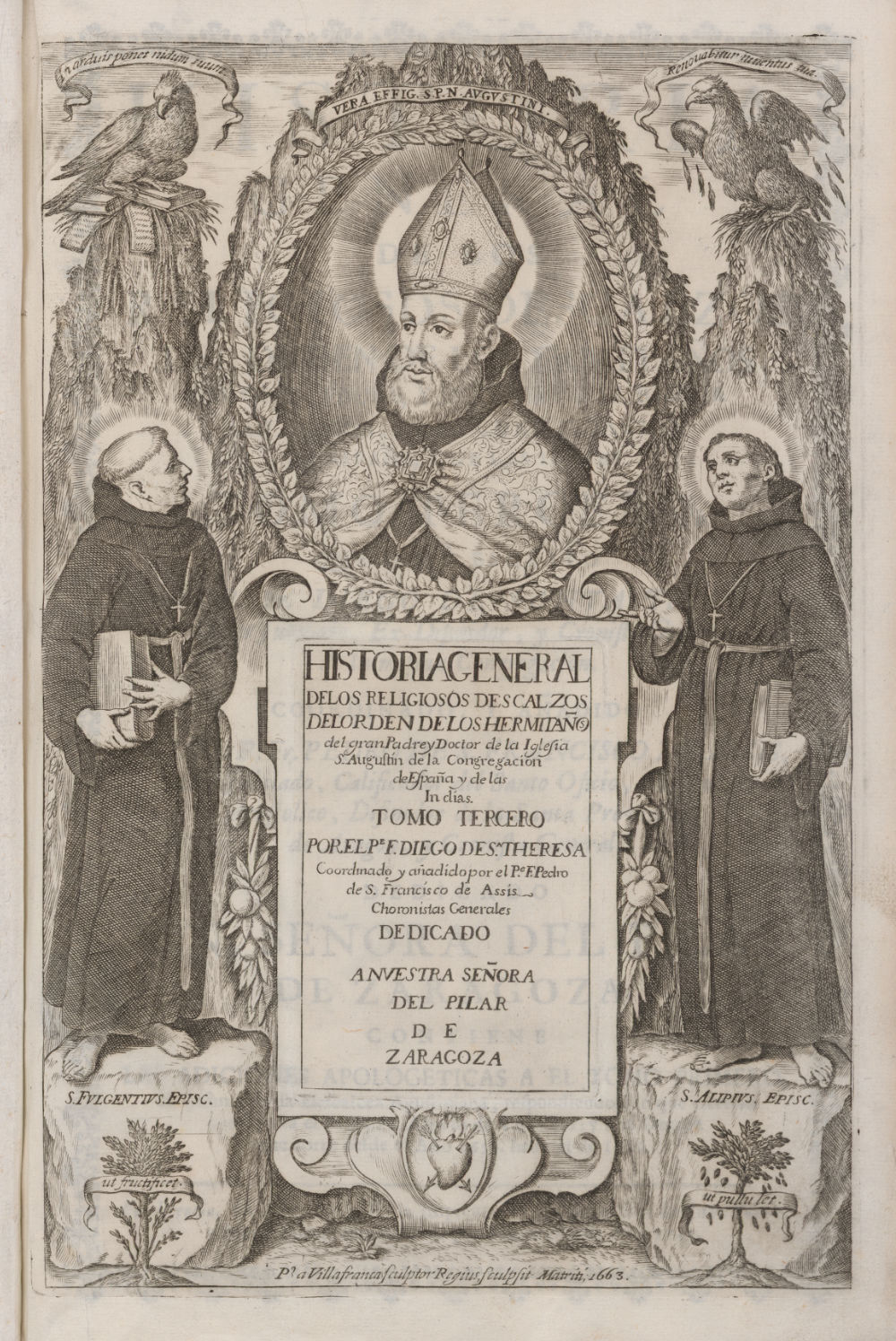

The principal sources for this study are histories of the Order of Augustinian Recollects, also known as “Discalced or Unshod Augustinians,” a Spanish mendicant reform order that sought a return to the primitive observance of the Rule of St. Augustine.4 The Recollects were one of the last orders established in the Philippines, where they were instrumental in efforts to reform the regular Augustinians, who were implicated in a series of scandals. The first mission arrived there in 1606.5 Chronicles emphasize successes in the evangelization of the archipelago, recounting the foundation of missions, narrating the deeds of illustrious friars, and enumerating miracle-working cult images and their origin stories.

The Origin Story

Fray Diego de Santa Teresa published an extended version of the origin story of the Ecce homo in 1743, writing that it was made for Juan de Araus, a Mexico City priest who sought a representation of Christ’s humility and patience to help subdue his fiery disposition (fig. 3). According to Santa Teresa, Araus commissioned the image from an unnamed sculptor whom he described as “a most exquisite and devout Artist” (un Artífice primorossimo, y devoto). In advance of making the image, both the priest and the artist prepared themselves through prayer and fasting. For the three years during which the work was in progress, they were sustained by frequent Communion, readings from the Gospel, and contemplation of the works of Christian mystics, including St. Gertrude and St. Bridget of Sweden. The chronicler also specifies that the material used to make the image is pasto, likely cornstalk paste (caña de maíz), a lightweight material well-suited to processional images. He goes on to describe an improbable artistic process of “adding and taking away” until it was finished to the priest’s liking. Araus venerated the image on an altar in his private quarters until fray Jacinto de San Fulgencio, en route to the Philippines with twenty-four Augustinian Recollect missionaries, asked him to give it up “for the consolation of Manila.” After his initial refusal to part with the image, Araus was stricken with unbearable pain, relieved only when he reversed his decision.6 The calamitous state of Manila, ruined by natural disasters, conflict, and economic collapse, called for both material and spiritual remedies. The inference was that an image of Christ in an attitude of patient submission to his torments could aid the city’s beleaguered residents.

This origin story is largely invented, but key details can be confirmed through other sources. Juan de Araus was indeed a priest of the parish church of Santa Catarina Mártir in Mexico City. He was a benefactor and hermano mayor of the Augustinian Recollects, and his gift of the image to the Manila mission is recorded in other sources.7 His allegedly passionate temperament, which led to “grave encounters with the powerful,” is consistent with accounts of his involvement in a bitter dispute over the administration of the Recollect Hospice in Mexico City, a clash in which fray Jacinto de San Fulgencio was also implicated.8 The Recollect friar had traveled to Spain in 1649 as a delegate (comisario) of the Philippine province to recruit missionaries and secure royal financing. He returned in the spring of 1652, encountering Araus in Mexico City on his way to Acapulco, where he embarked for Manila a year later, in 1653.9

Even though not every detail of Santa Teresa’s story is credible, it is nonetheless consistent with prevailing attitudes toward the making of sacred images. That is, the sacred resides in images made by devout artists, inspired by prayers, penances, and spiritual exercises. In his account of the making of the image of Christ, Santa Teresa specifically references the writings of St. Gertrude and St. Bridget of Sweden, whose vivid revelations of Christ’s suffering have long been recognized as sources for visual representations of the Passion.10 What is most striking about the friar’s account, however, is its emphasis on the spiritual preparation required for the making of a “devout” image imbued with the quality of sacredness or divinity. That the preparatory exercise is jointly undertaken by the priest and the artist recalls other histories of sacred images, such as a copy of Nuestra Señora de la Soledad carved by Gaspar Becerra, who was aided by the prayers, alms, and penances of Minim friars in Madrid.11 In a similar story, Mariana de San José, founder of the Augustinian Recollect order of nuns, commissioned a sculpture of Christ at the Column for her convent in Madrid and stipulated that the artist should commence work on it while the nuns received Communion in order to ensure that the image was especially devout.12

Early written sources consistently refer to the Manila image as an ecce homo, although it was properly known as the Christ of Humility and Patience. In 1664, the Recollect chronicler Andrés de San Nicolás referred to it by that name and declared that it was one of the most venerated images in the islands. He described it as life-size and praised its manufacture as the “best that is known in those distant hemispheres.” The image of Christ, seated on a stone and resting his hand on his cheek, he wrote, “moved the hard heart of the most lost to trembling and devotion.”13 In 1743, Diego de Santa Teresa elaborated on its appearance:

The Holy Image is the natural size of a man; represented seated on a pedestal; his entire body is purple, signifying the cruel lashes he suffered because of the human race: His cheek rests on his right hand, his head tilted, and his body slightly turned to one side, so that his shoulders show many pitiful wounds; he is crowned with very thick, woven rushes; and in his left hand he holds the reed cane. The eyes, which are beautiful, seem to weep and gaze in all directions. The physique and symmetry of the body are most perfect, with every part a sum of beauties; and the hearts of those who look at it are moved to pity, even those who are adorned with diamonds.14

Augustinian Recollect writers were not the only ones to describe the image, although others focus less on its visual appearance than on subjective responses to it. The Dominican friar Domingo Fernández de Navarrete saw the image in the 1650s and wrote that it “moves all who see it to pious compassion.”15 In 1660, Alonso del Valle wrote that it was “the living impression of the scandals of Jerusalem . . . the sculpted consolation of the sinner’s afflicted tears.”16

The subject of Christ’s humility, with its emphasis on quiet self-negation, was eminently suited to the mental prayer methods of the Recollects, but devotion to the ecce homo was prevalent throughout the Spanish world. The most notable example in Mexico City is the so-called Señor del Cacao, a life-size image venerated in the Metropolitan Cathedral (fig. 4). Like the Manila Christ of Humility, it is made of cornstalk paste.17 The fabrication of the Manila image in paste as an episode (de pasto en un passo) representing Christ’s humility is stipulated by Santa Teresa and points to its having been conceived from the outset for processional use.18 The previously cited prewar photograph shows the image on a silver platform with lanterns to illuminate it during nighttime processions.19

Translation and Reception

In the early spring of 1653, after overwintering in Acapulco, the nine-hundred-ton galleon San Francisco Xavier prepared to depart for Manila with six hundred passengers, silver to sustain the colony and exchange for merchandise, dispatches and correspondence, trade goods, and personal belongings. The ship’s cargo included the image of Christ given to the Augustinian Recollects by Juan de Araus as well as a number of other works of art.20 Passengers included many high-ranking officials and clerics, including Sabiniano Manrique de Lara (1609–1679), the new governor and captain general of the Philippines, and Miguel de Poblete (1602–1667), the incoming archbishop. Other passengers included an infantry company of one hundred soldiers and fifty Augustinian and Jesuit missionaries.21 The new governor-general, Manrique de Lara, was a Knight of Santiago descended from a noble family of Málaga. His military career included five years of imprisonment in Portugal following the dissolution of the Iberian union in 1640. After his release, he was made castellan of the fortress that guarded the Port of Acapulco. He was the highest authority of the port, in charge of receiving and dispatching the Manila galleons and overseeing the fair where imported merchandise was traded.22 After being named governor of the Philippines in June 1651, Manrique de Lara left Acapulco for Mexico City, where he spent the next two years making preparations and procuring funds for the journey to Manila, which was delayed until March 1653 for lack of a ship to transport him.23 Poblete, born in Mexico, was the first creole archbishop of Manila, a post to which he was named in 1647. He was not consecrated until 1650 and did not take possession of the seat until his arrival in Manila in 1653.24 Poblete had previously been maestrescuela of Puebla Cathedral, whose powerful bishop, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, was his protector.25

While passengers waited to depart for Manila, the image of Christ of Humility was venerated in the Acapulco parish church of San Pablo. On March 2, 1653, the afternoon prior to their embarkation, the Recollects, accompanied by the governor, archbishop, missionaries, and townspeople, carried the Christ of Humility in procession to the beach, where it was received with artillery salvos and then loaded onto the ship. During the transpacific crossing—a journey of almost five months—the image of Christ was used to arouse the devotion of passengers and petition for divine aid and protection. By the time the ship arrived in Manila, it had already been acclaimed as a miracle-worker, credited with curing gravely ill passengers and rescuing the ship from violent storms. According to Diego de Santa Teresa: “They put it on board the ship San Francisco Xavier, in a place where everyone could have it in their presence and ask it for help from the recurring perils of the waves; which they did, with many pious petitions and fervent novenas.”26 The same missionaries, on the transatlantic leg of their journey, had performed spiritual exercises as if they were in their convent. They preached in the afternoons, persuaded sailors to pray the rosary, gave the Sacrament of Penance to sinners, and provided instruction in Christian doctrine.27 The ship’s transformation into a place of worship and religious instruction is a recurring theme in histories of religious orders with overseas missions.28 While it attests to actual religious practice, the chronicler’s narrative is also informed by Christian allegories of the Ship of the Church, endangered by demons and tempests. In a late seventeenth-century Hispano-Philippine ivory, the Ship of Religion is rowed by members of religious orders (three friars and a Jesuit), whose labors propel it through dangerous waters toward the safe harbor of Salvation (fig. 5).29 The Cross serves as the ship’s mast, and symbols of the Passion emblazon the pennant and sail. The Virgin Mary, her head encircled by a radiant halo and her heart pierced by the sword of sorrow, is a passenger.

Sacred images often aided religious practices and rituals intended to assure the safe passage of ships, and passengers on the Manila-bound galleon in the spring of 1653 were accompanied by at least two: Christ of Humility and Patience and Our Lady of Good Voyage and Peace (also known as Our Lady of Antipolo) (fig. 6). According to the Jesuit chronicler Diego de Oña, the image of Christ was placed next to that of his mother on the ship, and under their watch, there was nothing to fear.30 The latter image is said to have come from a church in Acapulco, where Juan Niño de Tavora, governor-elect of the Philippines, encountered it in 1626 and took it with him to Manila. The diminutive image of the Virgin Mary protected that galleon during the transpacific crossing, and the grateful governor gave it to the Jesuits for their church in Antipolo (in the mountains east of Manila). After miraculously escaping destruction during the sangley uprising of 1639, the image was taken to Manila’s Royal Chapel. In 1646, it was moved to Cavite, Manila’s harbor, to safeguard the city from Dutch attacks. The image purportedly crossed the Pacific eight times as protectress of the galleon. In gratitude for the safe arrival of the San Francisco Xavier in 1653, the incoming governor and archbishop vowed to restore the Virgin to her church in Antipolo and bestowed the title Nuestra Señora de la Paz y Buen Viaje.31

On June 26, after almost four months on the open sea, the San Francisco Xavier entered the waters of the Philippine archipelago through the Strait of San Bernardino. Up to this point, the voyage had been miraculously uneventful. Diego de Oña observed that only three passengers had died en route and took it as a sign that the ship brought good health to the islands. He attributed the successful voyage to higher causes, specifically to “God made human, adored in a most tender image of the ecce homo, a precious treasure brought by the Recollect fathers for their church, and his Holy Mother, adored in the admirable image of Antipolo.”32 The ship was nearly lost before reaching Manila, but on July 23, it cast anchor at Cavite, the first Spanish vessel to do so in fourteen years.33 The significance of the occasion was accentuated by the fact that Cavite had ceased to be the principal port of the archipelago during the 1640s, as the galleon was diverted to Lampón (Lamon Bay) to avoid the Dutch blockade.34 The governor and the archbishop disembarked the day before, and on the beach, Poblete blessed the land and then blessed Manrique de Lara, who had symbolically ceded primacy to him (and to the Church) in the act.35 This was the first in a series of public acts, both civil and religious, that followed the arrival of the galleon. The archbishop and governor, as heads of church and state, made public entries into the city of Manila on July 24 and 25. The splendor of these events (which the city could ill afford) confirmed the power and continuity of the Spanish monarchy and the Catholic church in a distant city imperiled by acute political, economic, and spiritual crises.36 The public spectacle of Manrique de Lara’s entry stood in stark contrast to his own assessment of the dire situation on taking possession of the government. In a report to King Philip IV, he wrote, “I found these islands in a miserable state and in their final gasp.”37 At the time of Poblete’s entry, the episcopal seat of Manila had been vacant for twelve years. His predecessor, Hernando Guerrero, who was banished from Manila by the governor in 1636, died in 1641; his would-be predecessor, Fernando Montero de Espinosa, died en route to Manila and entered the city in 1645 as a cadaver.38 The exile of Archbishop Guerrero was pinpointed by some chroniclers as the shameful cause of Manila’s castigation by God.39 Archbishop Poblete delivered a remedy in the form of a papal brief by Innocent X absolving inhabitants of the Philippines of their sins and conceding plenary indulgences to those who sincerely confessed them.40

On arrival in Manila, the Christ of Humility was initially taken to the monastic church of St. John the Baptist in Bagumbayan, located just outside the city walls. The monastery was the first one established by the Recollects in the Philippines.41 The miracle-working image was placed on an altar, where it attracted the devotion of the local community and that of the governor and archbishop, who were said to have visited it daily in gratitude for their safe passage from Acapulco.42 It remained in Bagumbayan for almost three months, until it was carried in procession to its permanent location in the intramuros church of San Nicolás de Tolentino, the Recollect Province’s patron saint. The church was newly rebuilt, having collapsed in the earthquake of 1645.43 On October 16, the governor prayed an all-night vigil in the Bagumbayan church and the next morning received the Sacrament of Penance. Festivities continued with dancing, artillery salvos, and the gunfire of both Indigenous and Spanish militias. On October 18, the image was carried beneath a canopy of branches in a solemn procession led by the archbishop to the church of the Misericordia (which served as a provisional cathedral). The next morning, the Recollect fathers carried it on their shoulders in procession to the church of San Nicolás and placed it on a side altar.44 There, the image became the focus of the daily devotions of the governor, whose public displays of piety were praised by chroniclers and emulated by other worshippers (fig. 7).45 The eighteenth-century Recollect historian Juan de la Concepción observed that, following the governor’s example, devotion to the Christ of Humility was universal, and feasts were celebrated annually with costly brilliance. In his own time, he noted that “this fervor has greatly diminished; fashion also has its use in devotions, and the most flamboyant ones attract attention.”46 Indeed, the image with the most prominent cult in the church of San Nicolás was not the Christ of Humility, but Christ the Nazarene, said to have been brought from New Spain to the Philippines in 1606 by the first Augustinian Recollects. The San Nicolás–based confraternity of Nazarenos carried it in procession on Holy Thursday, taking it out at midnight, and on Holy Monday, in the afternoon.47 The Ecce homo was the focus of passional devotion on Good Friday, but in a measure adopted by the provincial chapter in 1663, the Nazarenos were forbidden to carry it in processions except in the case of “most urgent necessity.”48 The injunction points to the use of the image in Rogation processions in connection with extraordinary emergencies and calamities, such as those organized during the previous year, when the city was threatened by the Chinese archpirate Zheng Chenggong (known to the Spanish as Koxinga).49

Calamity and Consolation

In 1654, on assuming his duties as the new governor of the Philippines, Manrique de Lara reported to Philip IV that he found the islands “in tears from calamities and miseries.”50 Another informant, Magino Sola, the Jesuit Procurator General of the Philippines, contrasted Manila’s former splendor with its current ruin: “Today you look so abused, so oppressed, so poor, and so lacking in the strength you used to have, that if you once had enough to aid and enrich other kingdoms, today you do not have enough to sustain yourself . . . with reason then you weep over so many calamities, so many misfortunes, and so much poverty.”51 The catastrophic earthquake that occurred on November 30, 1645, during the feast of San Andrés, patron saint of the city, was of such magnitude that it caused the literal collapse of the city. Most of the city’s principal buildings were destroyed or badly damaged, including the cathedral, governor’s palace, Real Audiencia, colegio of Santo Tomás, and the convents of Santo Domingo and San Nicolás de Tolentino. According to one eye-witness report, “Only a shadow of Manila remained.”52 Bleak assessments detailing Manila’s misfortunes and miseries—conflict, earthquakes, typhoons, shipwrecks, epidemics—routinely attributed them to God’s displeasure with its sinful populace, likening it to the biblical city of Nineveh.53

Descriptions of Manila in which colonial officials and clerics describe the city’s degraded situation have no visual equivalents, with the possible exception of a seemingly serene view of Manila attributed to the Amsterdam cartographer Johannes Vingboons (1616/17–1670) (fig. 8). The scene includes a blockade fleet of Dutch ships at the entrance to Manila harbor. Dutch harassment of Spanish shipping, which culminated in attacks on Manila in 1646 and 1647, sparked a severe economic crisis, exacerbated by a series of maritime disasters that disrupted the provision of an already inadequate situado or socorro—the financial subsidy sent from New Spain to maintain the colony.

The Dutch were not the only threat faced by the Spanish in the Philippines. Other external threats included ongoing confrontations with regional sultanates (called moros by the Spanish) and the danger posed by Chinese and Japanese piracy. Internally, dependence upon and distrust of the large Chinese population of the Parián (so-called sangleyes) hastened violent uprisings and brutal repression in 1603, 1639, and 1662.54 The looming threat of an attack by Koxinga, whose demand for tribute was refused in 1662, provoked panic and interethnic violence in Manila. Rumors of sangley collusion with the Chinese underlie a miracle story in which a surprise attack was thwarted by Manrique de Lara thanks to warnings communicated by the Christ of Humility. According to Juan de la Concepción, a message was found at the feet of the image: “Governor, take care of your city, they want to surprise you.” The next day a more explicit message was discovered in the same place: “Governor, take care of your city, remove the scaffolding from the walls, do not trust anyone, you have enemies very near.”55 According to the story, Manrique de Lara promptly removed scaffolding that could have aided seditious sangleyes in scaling the city walls. In fact, the threat of imminent attack did cause the governor to strengthen the city’s fortifications and demolish buildings outside the walls, including churches and convents, that were close enough to serve as enemy positions.56 These defensive measures proved unnecessary when Koxinga died unexpectedly. Manrique de Lara evoked Celtiberian resistance to Roman conquest when he reported that “if the barbarian had not died nothing would have remained of we Spanish who inhabited the Philippines but memories, like those of Numancia.”57

Manrique de Lara’s personal devotion to the Christ of Humility is routinely cited by witnesses and repeated by later sources. By all accounts, the governor was genuinely devout, but his public acts of atonement and reparation were manifestly performative ones, enacted as the representative of a distant Catholic monarch. Military chaplain Alonso del Valle vividly recounted one such act in a festival book commemorating celebrations in Manila of the birth of Felipe Próspero (1657–1661).58 In August 1659, the galleon from Acapulco brought news of the long-awaited birth of an heir to the Spanish throne, assuring the continuity of the monarchy at a critical moment in the Philippines. The short-lived prince was born in Madrid in November 1657, almost two years before reports reached Manila. Church bells announced the news in Manila, followed by the celebration of a Mass in the Royal Chapel. Twenty days of festivities followed, with both solemn and joyful proceedings, including sermons and processions, as well as bullfights, mock jousts, and fireworks.59 On the day the governor received the news, he rushed by carriage to the church of San Nicolás, where he humbled himself before the image of Christ and gave thanks to “the daily guarantor of his government.”60 According to Alonso del Valle:

Prostrate, he gave thanks to the holy Ecce homo; miraculous carved figure of devotion, living impression of the scandals of Jerusalem, exact image of the painful sorrows of the Just, sculpted consolation of the sinner’s afflicted tears. To this celestial wonder of earth, which he reverently visits every day, to whom he commends the discreet prayers of human error, with whom he sweetens the bitterness of high command, from whom he recognizes the advent of mild successes, he made exemplary sacrifice of his joys in order to guarantee the credit of eternal ones in faith.61

The burden of the office of governor and captain general of the Islands consoled by a sacred image of Christ is not only an evocative representation, in this case, it is also poignant. Manrique de Lara’s corporeal mortification and performative disengagement from worldly affairs anticipated his actual withdrawal. Initially hailed as “Governador Deseado,” by mid-1656, he had petitioned to be relieved of the post, citing poor health, which he traced to his imprisonment in Portugal and the rigors of Manila’s climate.62 He was silent about other tribulations, which only grew worse as he awaited a successor, who was not destined to arrive until 1663.63 Manrique de Lara returned to his native Málaga, having renounced its governorship, and became a priest.64

The festivities that celebrated the birth of Felipe Próspero in 1659 were staged in a ruined city. The earthquake of 1658 had wrecked many of the buildings constructed after the devastation of 1645, including the Recollect church of San Nicolás. When the governor went there after receiving news of the royal birth to prostrate himself in prayer before the Christ of Humility, it was in a provisional church not rebuilt until after 1666.65 The ruinous state of the church of San Nicolás, the departure of the governor, and the diminished fortunes of the Recollects in Manila all likely contributed to the waning fervor of devotion to the Christ of Humility and Patience.66 At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Augustinian chronicler Casimiro Díaz observed that the value of the governor’s example was magnified in a land where even devotions were changeable and, like a style of clothing, everyone dressed in what the governor was wearing.67 During Manrique de Lara’s ten years as governor of the Philippines, religious engagement with Christ’s Passion, aroused by a celebrated image from Mexico, was inextricably bound to a political culture shaped by economic precarity and spiritual crisis. Recognized as a miracle worker from the moment of its transfer to Manila, the image was enshrined on altars and paraded in the streets and plazas of the city in public rituals of salutation, petition, and atonement. These acts of performative piety, whether individual or collective, were also acts of governance that linked the expiation of sin to the consolation and repair of Manila.

Notes

-

“El Santo Cristo de la Paciencia,” Excelsior: Revista decenal ilustrada 4, no. 72 (April 20, 1908): 1067. I am grateful to Regalado Trota José for sharing this reference. ↩︎

-

Andrés de San Nicolás, Historia general de los religiosos descalzos del orden de los hermitaños del Gran Padre de la Iglesia San Agustín, de la Congregación de España y de las Indias, vol. 1 (Madrid, 1664), 441–42; Diego de Santa Teresa, Historia general, vol. 3 (Barcelona, 1743), 241–45, 365; Juan de la Concepción, Historia general de Philipinas. Conquistas espirituales y temporales de estos españoles dominios, establecimientos, progresos, y decadencias, 14 vols. (Sampaloc, 1788–89), 6:387–94, 7:49–51. ↩︎

-

Domingo Fernández de Navarrete, Tratados históricos, políticos, ethicos y religiosos de la monarchia de China (Madrid, 1676), 324; Diego de Oña, Labor evangélica. Ministerios apostólicos de los obreros de la Compañía de Jesús, segunda parte (ca. 1701) del Padre Diego de Oña, SJ (1621-1755), ed. Alexandre Coello de la Rosa and Verónica Peña Filiu (Silex, 2020), 762, 775; Casimiro Díaz, Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas; la temporal, por las armas de nuestros Católico Reyes de España, y la espiritual, por los religiosos de la orden de San Agustín (Manila, 1718; reprint Valladolid, 1890), 529; Pedro Murillo Velarde, Historia de la provincia de Philipinas de la Compañía de Jesús (Manila, 1749), 210. ↩︎

-

Ángel Martínez Cuesta, “Recolección agustiniana: origen, historia y espiritualidad,” Revista Agustiniana 48, no. 145 (2007): 57–76. ↩︎

-

Pedro Luengo, The Convents of Manila (Ateneo de Manila Press, 2018), 94. ↩︎

-

Santa Teresa, Historia general, 242–43; Concepción, Historia general, 387–90. ↩︎

-

San Nicolás, Historia general, 441; Santa Teresa, Historia general, 196–200. ↩︎

-

Both fray Jacinto and Juan de Araus had ties to Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, bishop of Puebla. Santa Teresa, Historia general, 195–200, 242; Ricardo Fernández Gracia, En las entrañas del atardecer de Palafox en Puebla. Deberes y afectos encontrados (Idea, 2020), 92–94. ↩︎

-

Santa Teresa, Historia general, 174–75. ↩︎

-

Antonio Rubial García and Doris Bieñko de Peralta, “La más amada de Cristo. Iconografía y culto de santa Gertrudis la Magna en la Nueva España,” Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 83 (2003): 5–54. ↩︎

-

Javier Portús, “Verdadero retrato y copia fallida. Leyendas en torno a la reproducción de imágenes sagradas,” in La imagen religiosa en la Monarquía hispánica. Usos y espacios, ed. María Cruz de Carlos Varona, Pierre Civil, Felipe Pereda, and Cécile Vincent-Cassy (Casa de Velázquez, 2008), 241–42. ↩︎

-

Luis Muñoz, Vida de la venerable M. Mariana de S. Joseph, fundadora de la recolección de las Monjas Augustinas, priora del Real Convento de la Encarnación (Madrid, 1645), 318–19. ↩︎

-

San Nicolás, Historia general, 441. ↩︎

-

Santa Teresa, Historia general, 242. ↩︎

-

Navarrete, Tratados históricos, 324. ↩︎

-

Alonso del Valle, Prensados fastos, descriptivos mapas de festivas acclamaciones, y ponposos jubileos, con que inundo en perenes alegrias a la insigne, y siempre leal Ciudad de Manila, Diadema de las Philipinas (Manila, 1660), 3v. ↩︎

-

Manuel Toussaint, La Catedral de México y el Sagrario Metropolitano: su historia, su tesoro, su arte (Porrúa, 1973), 96, 156, figs. 1 and 65; Andrés Estrada Jasso, Imágenes de caña de maíz (Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, 1996), 98. ↩︎

-

Santa Teresa, Historia general, 242. ↩︎

-

“El Santo Cristo de la Paciencia,” 1067. ↩︎

-

The personal belongings taken to Manila in 1653 by Archbishop Miguel de Poblete included forty-two paintings and three sculptures. Cayetano Sánchez Fuertes, “Biblioteca, pinacoteca, mobiliario y ajuar de Don Miguel de Poblete, arzobispo de Manila,” Archivo agustiniano 95, no. 213 (2011): 399–444. ↩︎

-

Libro de cartas de Sabiniano Manrique de Lara, July 19, 1654, AGI, Filipinas, 285, N. 1, fols. 4r–v. ↩︎

-

William Lytle Schurz, “Acapulco and the Manila Galleon,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 22, no. 1 (1918): 24–25; for the biography of Sabiniano Manrique de Lara, see Navarrete, Tratados, 310–14; Luis de Salazar y Castro, Historia genealógica de la Casa de Lara (Madrid, 1696), 2:776–80; Ana María Prieto Lucena, Filipinas durante el gobierno de Manrique de Lara (1653-1663) (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 1984). ↩︎

-

Libro de cartas, AGI, Filipinas, 285, N. 1, fol. 16r. ↩︎

-

AGI, Filipinas, 2, N. 79; Gregorio Martín de Guijo, Diario, 1648-1664, ed. Manuel Romero de Terreros, 2 vols. (Porrúa, 1952), 1:126–27. ↩︎

-

For the biography of Miguel de Poblete, see Oña, Labor evangélica, 876–80; Eduardo Juliá Martínez, “Notas sobre El Dr. D. Miguel de Poblete, arzobispo de Manila,” Revista de Indias 3, no. 2 (1942): 223–49; Sánchez Fuertes, “Biblioteca,” 399–444. ↩︎

-

Santa Teresa, Historia general, 243. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 175. ↩︎

-

See “Voyage of Fr. Diego de Bobadilla to the Philippines (Manila, August 6, 1643),” in History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents, vol. 4, Religious Conquest, 1638–1670, ed. Rodrigue Lévesque (Lévesque Publications, 1995), 64–70. ↩︎

-

Margarita Estella, “La representación de la Nave de la Iglesia en un relieve de marfil,” Traza y baza 8 (1983): 97–101. ↩︎

-

Oña, Labor evangélica, 775. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 762, 766–75; Murillo Velarde, Historia, 210r–215v. For a recent study of the image, see Christina H. Lee, “Our Lady of Antipolo, Our Lady of the Tree,” in Saints of Resistance: Devotions in the Philippines under Early Spanish Rule (Oxford University Press, 2021), 100–26. ↩︎

-

Oña, Labor evangélica, 762. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 762–63; Díaz, Conquistas, 528; Santa Teresa, Historia general, 243. ↩︎

-

Libro de cartas, AGI, Filipinas, 285, N. 1, fol. 4r–v.; María Baudot Monroy, “Lampón, puerto alternativo a Cavite para el galeón de Manila,” Vegueta: Anuario de la Facultad de Geografía e Historia 20 (2020): 21–48. ↩︎

-

Oña, Labor evangélica, 763. ↩︎

-

The public entries of the archbishop and governor are described in ibid., 764–66. ↩︎

-

Libro de cartas, AGI, Filipinas, 285, N. 1, 4v. ↩︎

-

Alexandre Coello de la Rosa, “Interregnos en el cabildo metropolitano de Manila (1641-1653),” Colonial Latin American Review 32, no. 3 (2023): 369, 380–83. ↩︎

-

Oña, Labor evangélica, 780–81. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 778–81; Díaz, Conquistas, 531–32. ↩︎

-

María Lourdes Díaz-Trechuelo Spínola, Arquitectura española en Filipinas (1565-1800) (Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos de Sevilla, 1959), 27–28. ↩︎

-

The translation of the image to Bagumbayan is described by San Nicolás, Historia general, 441–42; Santa Teresa, Historia general, 244. ↩︎

-

The first church of San Nicolás was built in 1614–19. Díaz-Trechuelo, Arquitectura española, 251–53. ↩︎

-

The translation of the image to the church of San Nicolás is recounted in San Nicolás, Historia general, 442; Oña, Labor evangélica, 775; Santa Teresa, Historia general, 244–45. ↩︎

-

This photograph of the interior of the church (rebuilt in 1780) appears in Ricardo Jarauta Fuentes de la Consolación, Album de la Orden de Agustinos Recoletos: con motivo del XV centenario del glorioso transito de San Agustín (1931). I am grateful to Fr. Rene Paglinawan, OAR, for providing the image and sharing the reference. ↩︎

-

Concepción, Historia general, 6:394. ↩︎

-

Valeriano Sánchez Ramos and Carlos Villoria Prieto, “La cofradía de Jesús Nazareno de Manila (Filipinas),” in Las cofradías y hermandades de Jesús Nazareno y Nosso Senhor dos Passos: Historia, arte y devoción, ed. Manuel Peláez del Rosal (Asociación Hispánica d Estudios Franciscanos, 2019), 1–16. ↩︎

-

Actas y determinaciones del capítulo Intermedio del año 1663 de la Provincia de San Nicolás de Tolentino (Orden de Agustinos Recoletos, 1663), https://agustinosrecoletos.org/wp-content/uploads/library/76-capitulos-de-la-provincia/861-cappsnt-1663.pdf. ↩︎

-

Prieto Lucena, Filipinas, 140; Dana Leibsohn, “Dentro y fuera de los muros: Manila, Ethnicity, and Colonial Cartography,” Ethnohistory 61, no. 2 (2014): 242. ↩︎

-

Libro de cartas, AGI, Filipinas, 285, N. 1, 33r. ↩︎

-

Magino Sola, Memorial y carta del Padre Magino Sola de la Compañía de Jesús, Procurador general della, por la Provincia de Philipinas, para el señor Don Sabiniano Manrique de Lara, Governador y Capitán general de dichas Islas (Mexico City, 1652), 8v. ↩︎

-

Verdadera relación de la grande destruicion, que por permission de nuestro Señor, ha avido en la Ciudad de Manila (Madrid, 1649), unpaginated; Murillo Velarde, Historia, 138v–142r. ↩︎

-

Oña, Labor evangélica, 664; Díaz, Conquistas, 531–32; Murillo Velarde, Historia, 229v–230r. ↩︎

-

Jean-Noël Sánchez, “A Prismatic Glance at One Century of Threats on the Philippine Colony,” in The Representation of External Threats: From the Middle Ages to the Modern World, ed. Eberhard Crailsheim and María Dolores Elizalde (Brill, 2019), 343–65; Ostwald Sales and Colín Kortajarena, “Apuntes para el estudio de la presencia ‘holandesa’ en la Nueva España: una perspectiva mexicano-filipina, 1600-1650,” in Memorias e historias compartidas. Intercambios culturales, relaciones comerciales y diplomáticas entre México y los Países Bajos, siglos XVI-XX, ed. Laura Pérez Rosales and Arjen van der Sluis (Iberoamericana, 2009), 149–76. ↩︎

-

Concepción, Historia general, 7:49–51. ↩︎

-

Prieto Lucena, Filipinas, 128–33. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 139. ↩︎

-

Valle, Prensados fastos. For empire-wide celebrations of the birth, see Inmaculada Rodríguez Moya, “La esperanza de la monarquía. Fiestas en el imperio hispánico por Felipe Próspero,” in Visiones de un Imperio en Fiesta, ed. Inmaculada Rodríguez Moya and Víctor Mínguez Cornelles (Fundación Carlos de Amberes, 2016), 93–119. ↩︎

-

Valle, Prensados fastos. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 3v. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 3v–4r. ↩︎

-

Francisco Combés, Governador Deseado (ca. 1654), University of Indiana, Lilly Library, Philippine Mss II; Petición de renuncia al cargo de Manrique de Lara, Cavite, July 15, 1656, AGN, Filipinas, 22, R. 10, N. 59. ↩︎

-

Prieto Lucena, Filipinas, 34–38. ↩︎

-

Díaz, Conquistas, 527. ↩︎

-

Díaz-Trechuelo, Arquitectura española, 251–53; Luengo, Convents, 94–103. ↩︎

-

Concepción, Historia general, 394. ↩︎

-

Díaz, Conquistas, 529. ↩︎