Historians have primarily framed the global networks centered between Asia and the Americas during the early modern era as a “silk for silver” commodity exchange. For centuries, silk was one of the primary luxury goods exported from China to Manila and exchanged there for silver extracted from the astonishingly rich caches at Potosí, in what is today Bolivia. This microhistory of a large set of Catholic church vestments made from Chinese silk explores global circulation during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries through an object-focused study of one component of that vast exchange (figs. 1, 2, and 10).1 This visual, analytical, and archival exploration offers a focused way to better understand Habsburg Spain’s connections to Asia and the world’s first global network.

This set of vestments, composed of ten separate elements, was made from a bolt of silk woven in China at some point in the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries (likely between 1580 and 1640). The set currently includes two dalmatics (a long priest’s tunic with broad, open sleeves), each with an accompanying collar, a chasuble (a priest’s armless tunic), a stole (a textile band worn around the neck), two maniples (a shorter band worn on the left arm during Mass), a baldachin, and a fragment of unlined cut silk.2 A chalice veil to cover the communion cup likely originally accompanied the other textiles, but given its small size, it is not surprising that the veil has not survived with the set. A private collector acquired the set in the 1920s from a small church in northern Spain, possibly Séron de Nágima in the province of Soria. Galerie Ruf, a textile dealer in Beckenried, Switzerland, purchased the group of vestments in the 1980s from the son of the collector and, finally, the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) acquired the set from the gallery in 2001. This is all that we currently know about the set from the archival record, but there are other avenues to unpack the set’s more than four-hundred-year history. A close analysis of the objects themselves can build an informative and interconnected narrative of the set’s long journey from China to Spain and its connection to a larger global history.

Chinese silks were first introduced to the Iberian world via the land-based trade networks connecting East and West Asia. Spanish weavers began incorporating Chinese motifs in their designs as early as the 1300s.3 But the quantities of Chinese silk that physically arrived in Europe were initially quite limited. More than one thousand patterned silks dating from the seventh to twelfth centuries are preserved in European church treasuries, but only one example is plausibly from China.4 The initial stylistic impact of Chinese silks in Europe was likely more indirect. European weavers could have adapted their designs from imported Persian and other Central Asian textiles that had been, in turn, influenced by Chinese textiles.

Ocean-based trade dramatically changed the volume of Europeans’ direct contact with Chinese silks, at least at the edges of the Spanish Crown’s empire. In 1594, García Hurtado de Mendoza, fourth marquis of Cañete and viceroy of Peru, noted that in the viceroyalties, “Chinese merchandise is so cheap and Spanish goods so dear . . . a man can clothe his wife in Chinese silks for two hundred reales, whereas he could not provide her with clothing of Spanish silks with two hundred pesos.”5 The Spanish Crown initially banned the importation of Chinese silks to the viceroyalties in an attempt to protect the Spanish textile industries’ new markets in the Americas. These edicts from the Crown were repeated (and often ignored) throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. In 1718, after the latest ban was implemented, Baltasar de Zúñiga, viceroy of New Spain, refused to implement it, noting that residents in Mexico preferred the Chinese imports and their relative affordability.6

Silk was imported from China in a variety of forms and levels of quality—raw and floss silk, threads, dyed and undyed bolts of cloth, and woven, embroidered, and painted silks. In Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas (1609), Antonio de Morga, a former lieutenant governor of the Philippines, described the various kinds of Chinese silk imported into Manila:

Raw silk, in bundles, of the fineness of two strands, and other silk of inferior quality; fine untwisted silks, white and of all colours, in small skeins; quantities of smooth velvets, and velvet embroidered in all sorts of patterns, colours and fashions; and others, with the ground of gold and embroidered with the same; woven cloths and brocades of gold and silver upon silk of various colours and patterns, quantities of gold and silver thread in skeins, upon thread and upon silk, but all the spangles of gold and silver are false and upon paper; damask, satins, taffetas, and gorvarans (sic), picotes (sic), and others cloths of all colours, some finer and better than others.7

Elite households in the Americas utilized imported Asian silks for domestic furnishing textiles as well as for personal clothing.8 But the Catholic Church was also a voracious consumer of imported Asian textiles for liturgical vestments and altar coverings. The earliest documented use of Chinese textiles for religious purposes in the Iberian world is in the 1521 inventory for King Manuel I of Portugal, who owned a vestment made of Chinese brocaded silk.9 Archival records from the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries document numerous examples of vestments constructed of Chinese silk and intended for churches in the viceroyalties and throughout Spain and Portugal. Pedro Martínez Buytrón, a priest who died in Mexico City in 1596, had a large collection of Chinese export silk vestments in his possession. Buytrón’s estate inventory included a set of purple taffeta garments with a chasuble, a stole, and a maniple. Buytrón also owned a second set of vestments made of black damask silk with yellow damask borders (chasuble, stole, and maniple) as well as two blue and white taffeta silk hangings lined with blue linen and with green and red fringes.10

Priests in the viceroyalties seemed to have been early adopters of vestments made from Chinese silk, but the fashion extended to Spain. In 1616, don Diego Vásquez de Mercado, archbishop of Manila, sent his nephew don Pedro de Mercado Vásquez, a regidor (alderman) of Madrid, a set of Chinese silk church vestments that included dalmatics, a chasuble, and a stole.11 Smaller Spanish villages also frequently received gifts from Asia as tribute or bequests from locals who had emigrated to the viceroyalties. Javier Pescador’s microhistory of a Basque region in northern Spain outlines the sustained donations of Asian goods from expatriates throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to small parishes (and family members) in the region.12

The earliest documented and surviving set of Chinese export silk vestments is preserved in Portugal. The set was ordered in Macau in 1634 by a “very rich and honored Chinese mandarin esteemed for his virtue,” named Francisco Carvalho Aranha, and sent to the brotherhood of Bom Jesus de São Marcos at the church of Santa Cruz (Braga).13 The set included two chasubles, two dalmatics, and a cope (a priest’s wide cape) as well as three altar frontals, a cross cover, a pulpit fall, and a baldachin. Each of the components in the set, made of cream satin silk and crimson velvet silk, was elaborately embroidered with gold and silver thread in a stylized pattern of intertwining vines. Some of the components also incorporate the symbol of the brotherhood. Likely guided by the patron, the tailors and embroiderers who assembled the set in China worked with a clear understanding of the desired forms and ornamentation of these European-style religious textiles.

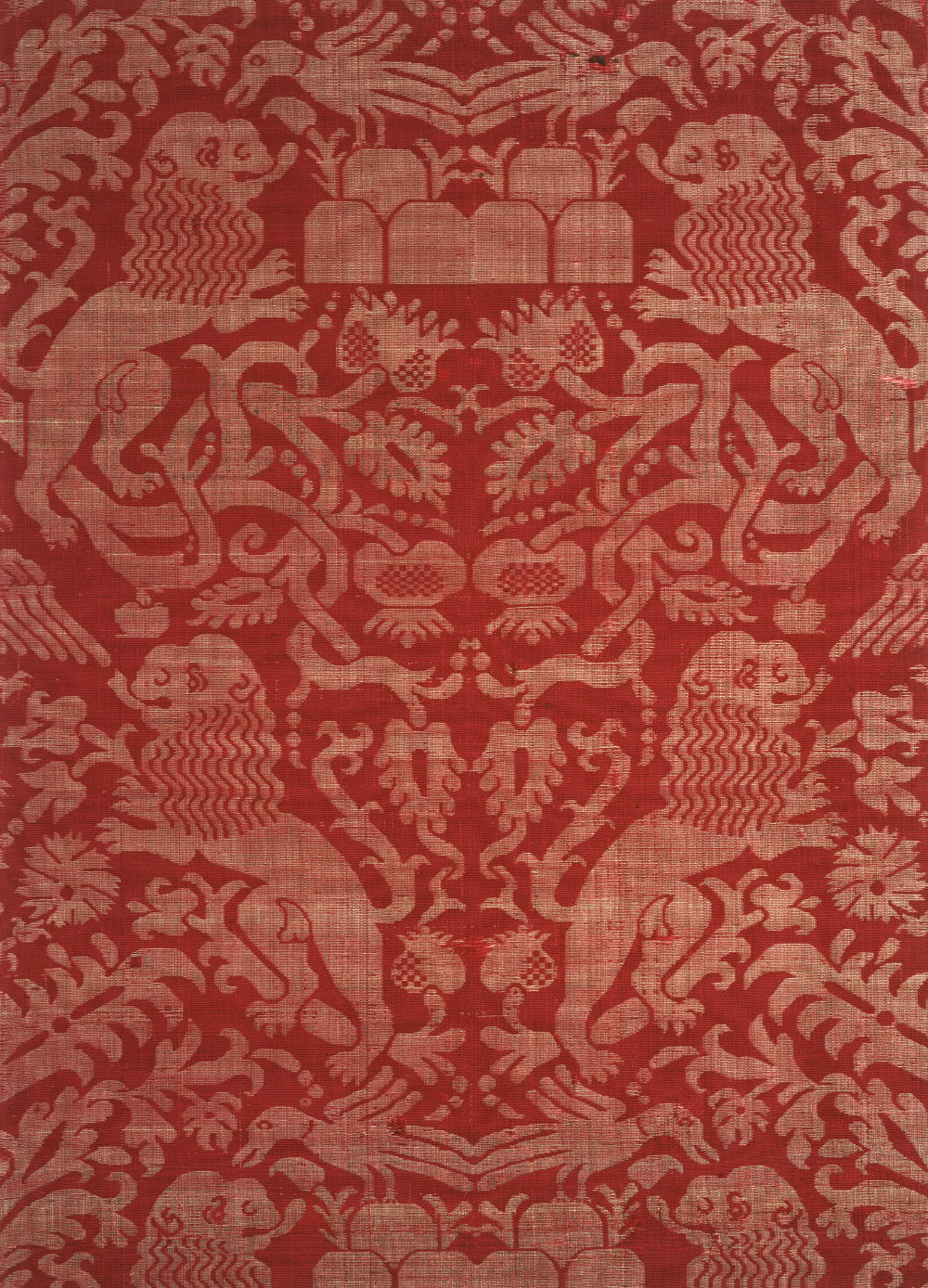

Unlike Aranha’s fully assembled gift to the brotherhood of Bom Jesus, the set on which this study is based was assembled in Spain using a bolt of imported Chinese silk.14 Antonio de Morga’s description of “brocades of gold and silver upon silk of various colours and patterns” best describes this long and sumptuous bolt. Woven in China in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, this textile has a complicated weave structure and would have been an exceptionally expensive silk when first commissioned and produced.15

All woven textiles are composed of warp and weft threads. Warp threads run vertically and are the fixed threads that attach to a loom during weaving. Weft threads cross over and under the warps in different configurations to create a woven textile. Compound textiles such as this example are created on large and complex drawlooms with multiple shafts manipulated by the weavers. Composed of a crimson red silk satin warp with wefts in blue, green, and white silk, the weaver has augmented the design with discontinuous supplementary gilded paper wefts brocaded into the textile (fig. 3). Unlike the woven elements of the design, the black eyes of the lions dispersed throughout the design are painted onto the textile.

The creators of this Chinese brocaded silk wove a pattern with a 28½ inch repeat that features a pair of guardian or rampant lions among scrolling foliage and surmounted by a European crown. This striking combination of motifs is derived from Chinese domestic textiles and European—likely Spanish or Italian—silks imported into China. The guardian lions that dominate the design bear a close resemblance to those found on textiles made for Chinese officials, such as a tapestry woven rank badge from the fifteenth century (fig. 4).

As early as the fourteenth century, Chinese imperial decrees outlined sumptuary laws for officials of various ranks. To identify their rank, Chinese civil and military officials wore woven or embroidered badges on the front and back of their robes. Within the elaborate hierarchies of power in late Ming imperial China, there were more than twenty different kinds of badges decorated with animals to identify an official’s rank. First and second rank military officials typically wore a badge ornamented with a lion.16 The lions in both the rank badge and the bolt of cloth feature wide eyes, open toothy grins, and bushy green tails typical of those found on Chinese textiles from the late Ming dynasty. While the rank badge features only one lion, the silk bolt features pairs of guardian lions chasing a brocaded ball, a familiar motif in Chinese iconography that was often regarded as a symbol of happiness (fig. 5).

The charming creatures on the silk bolt are not an exclusively Chinese element—they also recall rampant lions, a symbol of nobility in European heraldry. The Chinese weavers may have used Spanish and Italian lampas silks imported to China in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as design sources for these rampant lions. A fifteenth-century Spanish lampas silk features a pair of crowned and confronting lions in the midst of scrolling foliage (fig. 6). The undulating plant forms and whimsical animals within this design relate to earlier textiles produced in Spain under the Nasrid dynasty, who ruled the Iberian Peninsula prior to the Christian conquest in 1492. Fragments of silk in this design are preserved in multiple public collections, including at least one that was formerly part of a chasuble.17 The design of a late-sixteenth- or early-seventeenth-century Italian or Spanish silk bears an even closer relationship to the Chinese silk bolt (fig. 7).18 These fragments are examples of the kinds of European textiles that could have been sent to China to serve as design sources for the Chinese weavers.

The Chinese silk’s design repeat also includes a large and distinctly European crown floating above the heads of the guardian lions. The pointed crown, primarily composed of gilded paper, has a brim with a crosshatched pattern in green, blue, and gold and is augmented with two round green jewels encircled in blue. The scrolling vines undulating throughout the background are interspersed with three different types of flowers—one type is likely a chrysanthemum, a motif found frequently on Chinese damask silks made for the domestic market (fig. 8).19 All of these textile designs highlight how weavers in multiple locations around the globe were part of a robust international exchange of design motifs that spanned centuries.20

The combination of Asian and European motifs incorporated into the pattern for the PEM silk helps identify it as Chinese, but there are other distinguishing features that support a Chinese attribution. One of the most reliable ways to identify a Chinese textile—particularly a simple weave without a design or further embellishment—is the width of the textile. Selvage-to-selvage widths of Chinese silks are typically much wider than their European counterparts (26 to 31 inches wide vs. 19½ to 23 inches wide).21 Many Chinese silks also have selvages woven in a contrasting color. Yet another distinguishing feature of many Chinese silks is the presence of sequential holes in the selvages. These holes are evidence of a pair of crossed rods—sometimes called temple rods—used by weavers to help maintain a symmetrical fabric width during weaving. Chinese silks also have a soft, clinging “hand” that is the result of mechanical calendering.22 The selvage-to-selvage width of the bolt of silk used to create PEM’s set of vestments is approximately 28 inches. The selvage edges—only visible now on the surviving unlined silk fragment—are white. Also visible on the fragment, just inside the selvage edge, is a thin continuous line of yellow satin weave silk. Occasionally visible at the seams of different components of the set, these yellow silk lines presumably framed the edges of the fabric and would have aided tailors in matching up seams.

Early Chinese silks incorporating European motifs have traditionally been attributed to weavers in Macau. This is likely based on the assumption that the weavers would have needed direct contact with foreign agents to produce textiles incorporating European motifs, but there is limited evidence that Macau was an early center for silk weaving in China. Export ceramic production in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries can serve as a useful model for speculating on other plausible locations for the production of these early export silks. Potters in Jingdezhen during the late Ming dynasty successfully produced and exported customized ceramics incorporating global motifs despite being more than three hundred miles from the Chinese coastline. Using this customized porcelain production as a model, could these early export silks have been woven in one of a variety of silk production centers in southern China? Suzhou and Hangzhou produced high-quality silk for imperial and regional use during the late Ming dynasty, and Guangdong and Fujian provinces were also major silk production centers. Given that Hokkien merchants controlled the early Chinese junk trade from Fujian to Manila, perhaps the coastal cities of Fuzhou and Quanzhou could be plausible production centers for the complex silks exported to the Philippines during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Quanzhou, in particular, was known during the Ming dynasty for pattern weave silks and silks incorporating gold and silk thread.23 We can perhaps begin to test this assumption by conducting analysis of dyestuffs and other materials used in these textiles and reviewing their weave structures.

Xian Zhang from History Echoes Analytical Services is an analytical chemist with experience in natural dyestuffs, who studied several samples from the unlined fragment in PEM’s set. Her testing provides analytical information on the silk and reinforces the assertion that the textile was made in China. The crimson red silk that dominates the textile was dyed with lac, a traditional dye source used throughout Asia that is derived from the lac insect.24 The green silk used for the bushy tails of the lions and as a border for some of the motifs was dyed with indigo (blue) and pagoda tree buds (yellow). Pagoda trees (Styphnolobium japonicum) are native to central and northern China and Korea. The gilded strips selectively added throughout the textile are composed of a thin sheet of gold foil attached with a mixture of animal glue, kaolin clay, and laterite to a compound paper substrate. The foil layer is composed of 70 percent gold, 17 percent silver, and other minor elements, an alloy that is consistent with Chinese gold foil samples found on ancient textiles.25 Despite what Antonio de Morga wrote about these kinds of textiles in 1609, not “all the spangles of gold and silver are false and upon paper.”26

Weavers have been incorporating paper covered in gold foil into Chinese textiles for more than two thousand years.27 An English visitor to Hong Kong in the 1870s watched gold foil being produced while touring an alley near the street for silk embroiderers. He noted:

Several long, and narrow sheets of paper having been coated with a mixture of earth and glue are, in the next instance, covered either with gold, or silver leaf. In order that a bright, glossy appearance may be imparted to these sheets of paper . . . men rub them, heavily, from one end to the other, with pieces of crystal . . . [attached] to the ends of bamboo rods . . . the gilded, or silvered sheets of paper are [then] . . . cut, by means of large knives, into very thin strips.28

Once woven, this sumptuous bolt of lightweight, supple, and vibrantly colored silk would have been carefully packed and shipped from southern China to Manila. Beginning in the 1570s, Hokkien merchants from Fujian dominated the Chinese junk trade in Southeast and East Asia. Junks traveled from ports along the Fujian coastline—Quanzhou and Xiamen—as well as from Guangzhou and Macao—on vessels that typically weighed 350 tons and carried a crew of between two and four hundred men. Some of the largest had crews of close to five hundred.29 The journey from China to Manila typically took between fifteen and twenty days.

In 1589, eighty-eight Chinese junks were licensed for international maritime trade. By 1597, the licensed junks had increased to 137. Roughly half of those Chinese vessels were engaged with direct trade between Fujian and Manila.30 Smuggling was rampant, so it is difficult to pinpoint the precise numbers of junks trading with the Philippines, but it is estimated that between twenty and forty junks visited Manila annually between the late 1570s and the early 1640s. Silk made up the bulk of their cargoes, which the Hokkien merchants sold for as much South American silver as they could acquire, annually sending as much as 150 tons of silver back to China. Jerónimo de Salazar y Salcedo reported to the king in 1599 that the profits to be made on imported Chinese silk were as high as 400 percent.31

Hokkien merchants also resided long-term in Manila and ran the hundreds of retail shops in the Parián market just outside the walls of the city. But unlike the many Chinese silks offered in the market, this sumptuous bolt was likely a special commission and would not have been offered for retail sale. Chinese textile merchants were particularly skilled at folding and rolling textiles to the specifications of buyers to maximize the quantities of silk that could be packed. Once loaded into the hold of a galleon for the long journey across the Pacific Ocean from Manila to Acapulco, this special commission would have been transshipped across Mexico to Veracruz for reshipment and delivery in Seville. This bolt was likely commissioned for a high-ranking priest—either as a special commission he made for himself or as a gift from a colleague or family member. When a canon was appointed and received his prebend—the portion of the cathedral’s revenue allotted to a senior member of the church—it was typical for him to order a new set of vestments. At the cathedral in Huesca, Spain, for example, it was required that a newly appointed bishop present a chasuble, tunic, tunicle, two dalmatics, and three copes to the cathedral within three years of his appointment. These vestments often reverted to a cathedral’s collection upon a bishop’s death, a practice that accounts for the diversity of splendid textiles preserved within Spanish church treasuries to this day.32

The Spanish tailors who created this set of vestments lavishly used the imported silk bolt on the most significant and visible components of the set—the underside of the baldachin and the backs of the dalmatics and chasuble. But they also ensured the maximum use of this precious textile by thriftily piecing together small fragments of the silk to create the maniples and stole. The tailors also incorporated locally made textiles for both decorative and functional purposes when stitching the components together. Each piece is decoratively augmented with Spanish tape woven in red, white, and blue cotton (fig. 9). European tailors typically used this type of tape to reinforce and cover the seams of the narrow widths of European silks used on many church vestments. Given the wider width of Chinese silk, the tape on the PEM vestments is used more decoratively, often stitched on top of a single length of silk, rather than necessarily covering a seam.33 Various elements of the set were also lined with European linen to provide support for the especially thin and supple Chinese silk.

The baldachin is perhaps the most unusual component of the set to survive (fig 10). Baldachins are architectural canopies that mark and enclose a space in a religious, civic, or domestic environment. As noted in Rivas’s essay in this volume, textile canopies were sometimes hung above a throne or chair in the palaces and homes of the elite. The 1729 inventory of Carlos Bermúdez de Castro, archbishop of Manila, included a baldachin, which he used to display artworks.34 Baldachins used religiously typically hang above an altar or devotional image, suspended from above or supported on slender columns. Encountered on its own, this baldachin could have been made for either a domestic or religious setting, but its survival with accompanying religious garments made from the same Chinese silk indicates that it was likely designed to be used religiously.

Textile panels hang from the front and sides of the canopy, but not the back, indicating that the baldachin was likely suspended over an altarpiece against a wall.35 Iron rings stitched to the front corners of the baldachin once accommodated chains to suspend the canopy from the ceiling. Chinese silk fully lines the underside of the canopy roof so that during prayer or a service, a viewer gazed up at the glittering lengths of the silk’s beautiful design. The baldachin’s sixty-inch depth is greater than two widths of the Chinese silk, so the tailors carefully stitched a narrow length of the same silk between the two full widths that run from proper left to right underneath the canopy.

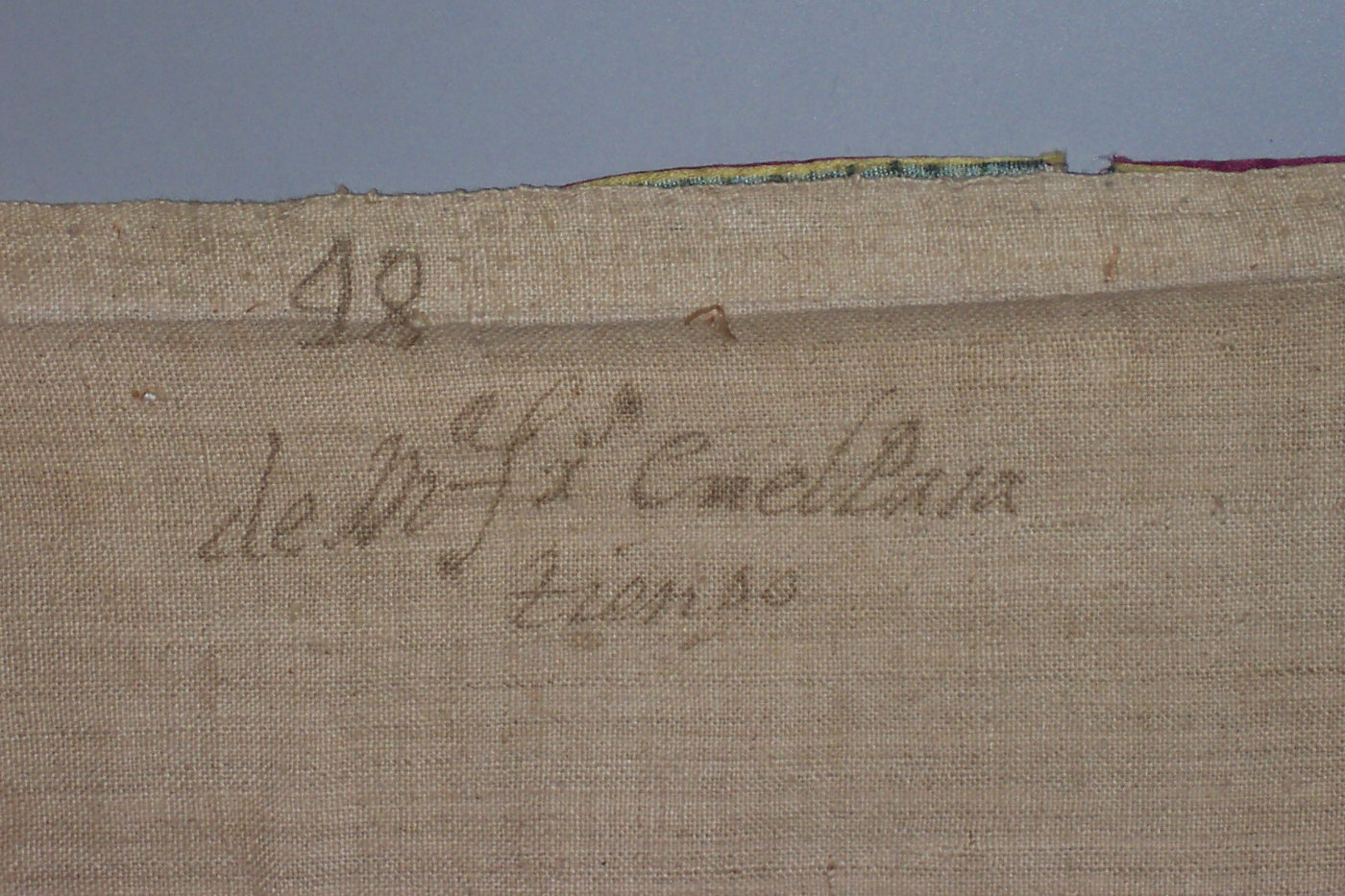

The narrow panels that hang from the canopy also feature sections of silk on the exterior, but the tailors economized by using a Chinese plain weave blue silk on the inside of the hanging panels. When the Peabody Essex Museum acquired the set, this blue silk lining survived only as fragmentary evidence, revealing that the tailors had sandwiched a stabilizing linen lining between the brocaded and blue silks for greater structure (fig. 11). When the canopy was originally in use, the lining would never have been visible. An inscription in ink preserved on the lining—“48 de Ma Frs en el pasatienpo”—offers an enigmatic but tantalizing clue to the set’s provenance (fig. 12). The “48” is possibly an inventory number for the church’s collection of vestments. Since Ma is typically shorthand for Maria, and Frs could be an abbreviation for Francisca, could this inscription document the participation of a female donor or seamstress in the creation of the set?36

The linen lining has an additional secret. While the front and proper right side panels were lined with lengths of plain linen, the tailors frugally recycled two different kinds of European block printed linen to line the proper left side panel (figs. 13 and 14).37 Printed with a mordant dye using madder root, the simple designs on these recycled panels were inspired by more sophisticated imported Indian cottons (fig. 15).38 Hiding in plain sight, these humble (and now rare) European linen fragments are another tangible link to the global network of exchange in textiles during this period.

Sets of vestments all made from the same fabric created a cohesive ensemble for feast days. The deep crimson red of the silk used for this set of vestments may indicate that it was used for a specific feast day or perhaps even during Holy Week, leading up to the celebration of Easter. The satin weave of the silk and the gilded paper floats would have undoubtedly sparkled brilliantly by candlelight during Mass.39 Preserved as a set for over four centuries, this rare group of liturgical textiles is a tangible link to the early global network of exchange between China, the Philippines, Mexico, and Spain and the power and wealth of the Catholic Church in this period.

Notes

-

The discipline of microhistory, first developed in the 1970s by Italian historians working with a cache of Catholic Church documents, is “based on the reduction of the scale of observation, on a microscopic analysis, and on intensive study of the documentary material.” Giovanni Levi, “On Microhistory,” in New Perspectives on Historical Writing, ed. Peter Burke (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992), 99. ↩︎

-

Not illustrated here are the collars for the dalmatics (AE85947.2AB and AE85947.3B), the maniples (AE85947.5 and AE85947.6), the stole (AE85947.7), and the fragment (AE85947.8) from the set. The surviving fragment had previously been stitched and lined with plain blue silk. ↩︎

-

Florence Lewis May, Silk Textiles of Spain: Eighth to Fifteenth Century (Hispanic Society, 1957), 119, 175–77. ↩︎

-

Anna Maria Muthesius, “The Impact of the Mediterranean Silk Trade on Western Europe Before 1200 A.D.,” in Textiles in Trade: Proceedings of the Textile Society of America Biennial Symposium, September 14–16, 1990 (Textile Society of America, 1990), 129. ↩︎

-

At the time, two hundred reales was worth about twenty-five pesos. Quoted in Woodrow Wilson Borah, Early Colonial Trade and Navigation Between Mexico and Peru (University of California Press, 1954), 122. ↩︎

-

Arturo Giraldez, The Age of Trade: The Manila Galleon and the Dawn of the Global Economy (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 153. ↩︎

-

Translated by and quoted in Teresa Canepa, Silk, Porcelain and Lacquer: China and Japan and Their Trade with Western Europe and the New World, 1500–1644 (Paul Holberton Publishing, 2016), 70. A gorgoran is a type of heavy East Indian silk cloth with stripes woven in two different weave structures. Florence Montgomery, Textiles in America 1650–1870 (W. W. Norton & Company, 1984), 247. A picot refers to a series of small loops along the edge of a piece of fabric. ↩︎

-

See Rivas’s essay in this volume for details on some domestic consumption. Chinese silks dominated the market in the viceroyalties, but elites also combined Castilian, Italian, and even locally produced silks into their households and wardrobes. For more on those breakdowns, see José L. Gasch-Tomás, “The Manila Galleon and the Reception of Chinese Silk in New Spain, c. 1550–1650,” in Threads of Global Desire: Silk in the Pre-Modern World, vol. 1, ed. Dagmar Schäfer, Giorgio Riello, and Luca Molà (Pasold Studies in Textile, Dress and Fashion History, 2018), 259–60. ↩︎

-

“Huũs esparamentos doratoreo de brocado da China,” cited in Maria João Ferreira, “Chasuble C-4,” in Encompassing the Globe: Portugal and the World in the 16th and 17th Centuries Reference Catalogue, vol. 2, ed. Jay Levinson (Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2007), 140. ↩︎

-

Archivo General de las Notarías del DF, Mexico City, Notario: Andrés Moreno (374), vol. 2464, 105–6, cited in José Luis Gasch-Tomás, “Asian Silk, Porcelain and Material Culture in the Definition of Mexican and Andalusian Elites, c. 1565–1630,” in Global Goods and the Spanish Empire, 1492–1824: Circulation, Resistance and Diversity, ed. Bethany Aram and Bartolomé Yun-Casalilla (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 171. See footnote 27 for a transcription of all the textiles in the priest’s estate. ↩︎

-

Archivo General de Indias (hereafter AGI), Seville, Contratación 1830, f. 850–52 and Contratación 1834, f. 1052–55, cited in José L. Gasch-Tomás, The Atlantic World and the Manila Galleons: Circulation, Market, and Consumption of Asian Goods in the Spanish Empire, 1565–1650 (Brill, 2019), 29–30. ↩︎

-

Javier Pescador, The New World Inside a Basque Village: The Oiartzun Valley and Its Atlantic Emigrants, 1550–1800, The Basque Series (University of Nevada, 2003), 37–38, 104. Thank you to Samuel Luterbacher for directing me to this fascinating study. ↩︎

-

Only a portion of the set survives. Ferreira, “Chasuble,” 140. See vol. 1, 284–85 for color illustrations. ↩︎

-

A related set of vestments, now dispersed, was made from a similarly long bolt of Chinese export silk with gilt paper floats woven between the 1580s and the 1640s. That silk bolt’s design incorporates Augustinian or Habsburg double-headed eagle motifs rendered in blue, yellow, and white silk on a red satin ground. Textile fragments from this large set survive in multiple public collections. See Royal Ontario Museum for a magnificent cope (973.422), the Rijksmuseum for a fragment of a chasuble (BK-1997-13), and the Victoria & Albert Museum for multiple fragments in the same design (T.215-1910, T.217-1910, and T.169-1929). ↩︎

-

Elena Phipps, Looking at Textiles: A Guide to Technical Terms (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011), 47; Florence Montgomery, Textiles in America, 1984, 274–75. ↩︎

-

Chen Juanjuan and Huang Nengfu “Silk Fabrics of the Ming Dynasty,” in Chinese Silks, ed. Dieter Kuhn (Yale University Press, 2012), 418–20. ↩︎

-

See also other textile fragments in variants of this pattern in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (11.23, 25.120.453, and 1981.372). ↩︎

-

Fragments of this red ground silk survive in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1971.240, 1972.66.1a, 1972.66.1b, and 1972.66.1c), Art Institute of Chicago (1973.308), Denver Art Museum (1972.131a-b) and Musée du Cinquantenaire in Brussels. A valance woven in this silk also incorporates a crowned double-headed eagle between the lions. See 1972.66.6 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and a fragment at Cora Ginsburg LLC. For more information on the pattern’s history and an illustration of a green ground version, see William DeGregorio and Michele Majer, Cora Ginsburg Catalog 2014 (Cora Ginsburg LLC, 2014), 4–5. I thank Martina D’Amato for her insights on these textiles. ↩︎

-

Canepa, Silk, Porcelain and Lacquer, 90. ↩︎

-

For related discussions on the global exchange of Asian and European design motifs during this period, see Elena Phipps, “The Iberian Globe: Textile Traditions and Trade in Latin America,” and Maria João Pacheco Ferreira, “Chinese Textiles for Portuguese Tastes,” in Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500–1800, ed. Amelia Peck (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), 28–55. ↩︎

-

Leanna Lee-Whitman, “The Silk Trade: Chinese Silks and the British East India Company,” Winterthur Portfolio 17, no. 1 (1982): 23–24. ↩︎

-

Whitman, “The Silk Trade,” 25. See also Aileen Ryan Earnest, “Trade and Commerce on the Pacific Coast in the Eighteenth Century: A Look at Some Chinese Silks of the Mission Period,” in Imported and Domestic Textiles in Eighteenth-Century America, ed. Patricia Fiske (The Textile Museum, 1975), 13. ↩︎

-

Chen and Huang, “Silk Fabrics of the Ming Dynasty,” 374–75. ↩︎

-

Xian Zhang conducted scanning electron microscopy, energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), and high-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detector and mass spectrometry (HPLC-DAD-MS) on the samples. The results are summarized in History Echoes Analytical Services LLC’s report 25AS01, February 3, 2025, Peabody Essex Museum object files for AE85947.8 ↩︎

-

For more on Chinese gold foil analysis, see J. Yang, J. Zhang and J. Jiang, “The Production Process of the Tang Dynasty Gold Thread Unearthed from the Underground Palace of Famen Temple,” Kaogu (Archaeology) 2 (2013): 97–104; and Y. Ma, “Microstructure and Composition Analysis of the Gold Thread in the Thangka and the Plaque with the Inscription ‘Long Live Emperor Kangxi’ Written by Him During the Qianlong Period of the Qing Dynasty in the Palace Museum,” The 9th Annual Conference of Chinese Conservation Society (2017): 469–78. ↩︎

-

Canepa, Silk, Porcelain and Lacquer, 70. Emphasis added. ↩︎

-

For an exploration of ancient gold foil weaving, see Zhao Feng, “Silks in the Song, Liao, Western Xia, and Jin Dynasties,” in Chinese Silks, 282–86. ↩︎

-

John Henry Gray, Walks in the City of Canton (De Souza & Company, 1875), 290. ↩︎

-

Giraldez, The Age of Trade, 161. ↩︎

-

James K. Chin, “The Junk Trade and Hokkien Merchant Networks in Maritime Asia, 1570–1760,” in Picturing Commerce in and from the East Asian Maritime Circuit, 1550–1800, ed. Tamara H. Bentley (Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 82. ↩︎

-

Letters from the royal fiscal to the king by Jerónimo de Salazar y Salcedo (Manila, July 21, 1599) cited in Chin, “The Junk Trade,” 91. ↩︎

-

May, Silk Textiles, 119–20. ↩︎

-

Note the related tape on the chasuble in figure 2 and a seventeenth-century Portuguese chasuble incorporating Safavid and European lampas silks in the Museu Abadede Baçal, Bragança [1063A], illustrated in Christianity in Asia: Sacred Art and Visual Splendour, ed. Alan Chong (Asian Civilisations Museum, 2016), 23. ↩︎

-

AGI Contaduría, 1283, f. 26v–r. I thank Kathryn Santner for bringing this reference to my attention. ↩︎

-

The surviving fragment (AE85947.8) bears evidence of blue silk lining and stitching and may have once hung from the back of the baldachin. ↩︎

-

I thank Kathryn Santner for deciphering the inscription and offering her insights on its possible meaning. ↩︎

-

Prior to the baldachin’s installation in the Sean M. Healey Gallery of Asian Export Art in 2019, textile conservator Deirdre Windsor developed an innovative framework to safely suspend and display it in the gallery. During the preparatory conservation, PEM opted to replicate the original blue silk lining on the side panels, which now obscures the linen lining including the block printed European linen fragments. Unlike the recycled fragments, the plain linen and tape used to line the other sides and the top of the canopy were likely new when the baldachin was first assembled. ↩︎

-

See related eighteenth-century European examples in The Metropolitan Museum’s collections (26.265.72 and 26.238.8). Thank you to Amelia Peck for facilitating a study day in 2018 at the Antonio Ratti Textile Center at The Metropolitan Museum of Art to research these fragments. For more on the relationship between utilitarian Indian and European block-printed textiles, see Janet C. Blyberg, catalog entry 97, in Asia in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age, ed. Karina H. Corrigan, Jan van Campen, and Femke Diercks with Janet C. Blyberg (Yale University Press, 2012), 328–30. ↩︎

-

Remnants of candlewax preserved on the chasuble’s linen lining presumably spilled onto the vestment from lit candles during Mass. ↩︎