It is impossible to walk through the historic center of the city of Puebla de los Ángeles (known as Puebla) without encountering the myriad shops lined with colorful glazed pottery, popularly known as talavera poblana.1 In addition to vibrant tableware, ceramic tiles adorn the walls and floors of religious and civic buildings including the endless church domes that define the city’s skyline. These colorful remnants speak to the long tradition that began nearly five hundred years ago with the founding of the city.

During the viceregal period of New Spain (1519–1821)—as Mexico was known—Puebla pottery gained widespread popularity across the Americas, reaching regions throughout Central and South America, the Caribbean, and present-day southeastern and southwestern United States. Despite fluctuations in production over the centuries, the tradition has persisted without interruption. Today, Puebla’s ceramic tradition is celebrated internationally; however, little attention is given to the individuals who created these renowned wares. This essay aims to shed light on the artisans behind Puebla’s famed ceramics and to associate specific pieces with the potters and their workshops.

The tools and techniques for producing tin-glazed earthenware were introduced to New Spain by Spanish potters, building upon the rich legacy of ceramic production that had flourished in Mesoamerica for thousands of years. Pottery in Mesoamerica was hand-built or mold-made, often adorned with colored slip and stamped designs, burnished for a smooth finish, and fired in pit kilns. The pottery of Cholula—located close to the city of Puebla—was particularly well developed by the time of the arrival of the Spanish and had enjoyed widespread circulation throughout Mesoamerica.2

Despite the appeal of Indigenous pottery, Spanish settlers sought the wheel-thrown, tin- and lead-glazed earthenware (also known as maiolica) they were accustomed to using in Spain. Initially, Spanish glazed ceramic ware was imported to the Americas from Spain; it met the demand of recent settlers and served as excellent ballast for transatlantic galleons. However, as the settler population grew, Spanish workshops could no longer supply sufficient wares. By the mid-sixteenth century, Spanish potters began to migrate to New Spain, bringing essential tools—such as the potter’s wheel, tin- and lead-based glazes, and updraft kilns—necessary for achieving a vitreous glazed ceramic ware.

The first known workshops of glazed ware in the Americas were established in Mexico City before 1537 by Spanish potters Francisco de la Reyna and Francisco Morales.3 While production continued in Mexico City, Puebla quickly emerged as the dominant center of ceramic manufacture by the end of the sixteenth century. Founded in 1531 as the second city of New Spain, Puebla was designed as an urban model for Spanish settlement and an industrial center for the manufacture of European-style goods. In addition to tin-glazed ceramics, the city produced soap, glass, and textiles.

If the location of Puebla was influenced by potters, they chose wisely. The climate was mild, the soil was rich, and there were extensive clay beds and raw sodium essential for glaze preparation. Ceramic workshops clustered in the center of the city, within blocks of the cathedral and central square. By 1653, when the potters’ guild was officially established, the church of San Marcos had become the seat for the trade. The town council (ayuntamiento) first designated the site as the parish church San Antonio Abad in 1538, long before the present facade of the church of San Marcos was completed in 1797 (fig. 1).4 While the name of the church changed a couple times before it was dedicated to San Marcos in the seventeenth century, it is believed to have always been the location where the potters’ confraternity and guild held meetings and celebrated festivities.5 The church of San Marcos is also named as a reference point for the location of workshops, underscoring the importance of the site as central area for Puebla potters. For example, in 1647 and 1660, the workshop locations of master potters Alfonso Sevillano and Nicólas de la Cueva were listed in operation “on the street of Plaza Publica, at the church of the Evangelist San Marcos.”6

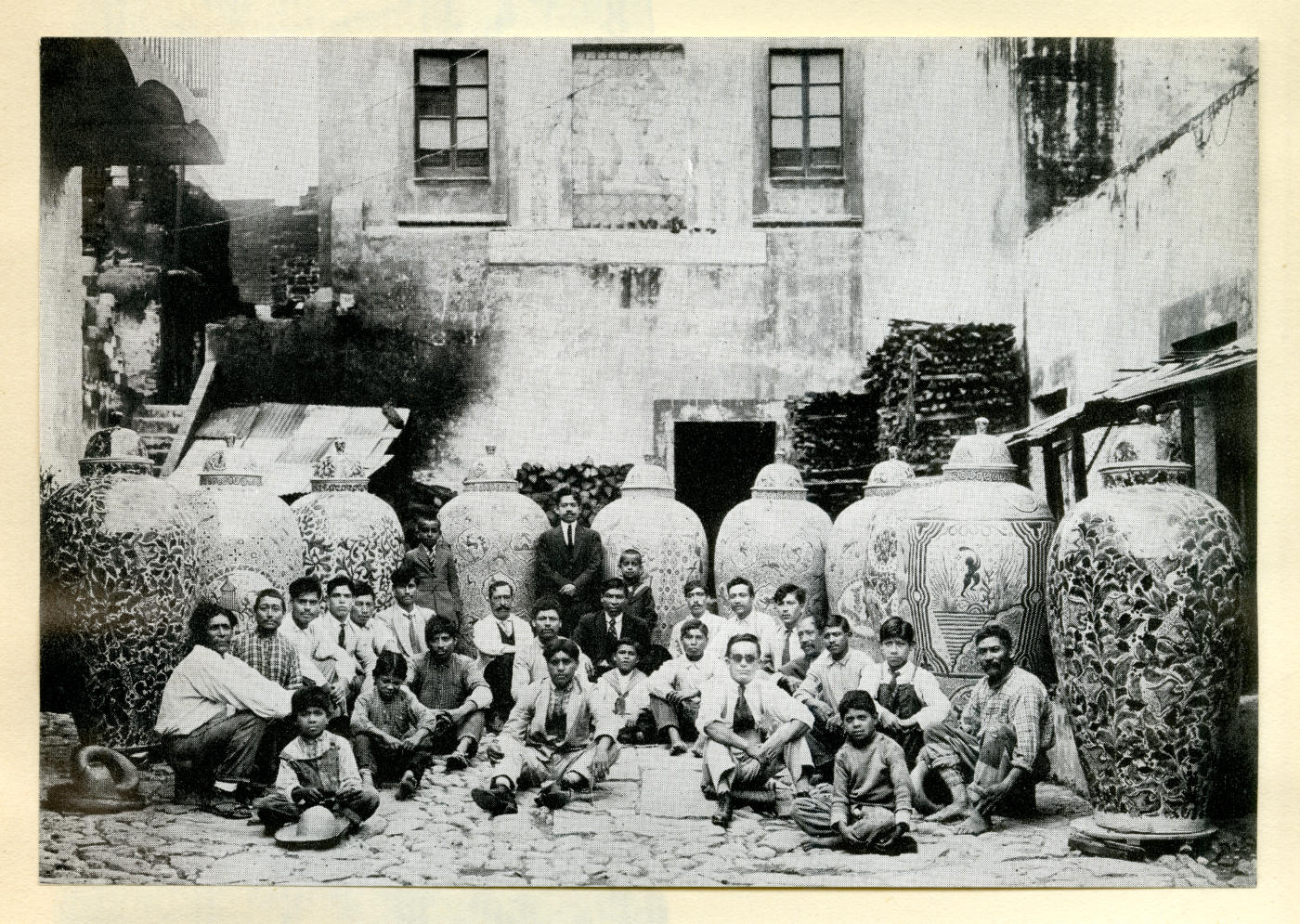

The first workshops in Puebla were situated on Calle los Herreros (“street of the blacksmiths”), indicating the proximity to other essential trades. As the industry expanded in the seventeenth century, workshops congregated along Poniente 700, including the workshops (lozerías) of Cabezas, Zayas, and Alfaro, which continued to operate for over two hundred years.7 The workshop of Cabezas, one of the largest workshops in the eighteenth century, was likely abandoned after a fire in the early twentieth century. Its two-story structure, adorned with brickwork, tiles, and cherubic figures, suggests its prominence. Nearby, the more modest Zayas workshop housed generations of potters dating back to 1674. Matrimonial records identify Nicolás de Zayas as a mestizo (a person of Spanish and Indigenous descent) and an “official potter of white ware” (oficial locero de lo blanco), with subsequent generations continuing the craft.8 Other known members of the Zayas family who became master potters include José de Zayas (active ca. 1714–30), Nicolás de Zayas (active ca. 1734), Sebastián de Zayas, the elder (el viejo) (died 1746), Sebastián de Zayas, the younger (el mozo) (born 1715, active ca. 1750), and Antonio de Zayas (active ca. 1772).9 A photograph from 1918 shows the building when it was owned by Pedro Padierna and his brother, visible behind a group of twenty-five members of their ceramic workshop proudly positioned in front of nine oversized jars made at the end of the Mexican Revolution (fig. 2).

Puebla potters were sufficiently organized by the last quarter of the sixteenth century, with their appointment of aldermen and inspectors. In 1573, Juan Vázquez served as alderman (alcalde) and Francisco Trujillo served as inspector (veedor).10 The alderman was the administrator and a link to city authorities, and the inspector was responsible for making periodic inspections of workshops to ensure the observance of required rules and regulations.

Production in Puebla became substantial enough by the mid-seventeenth century for the potters to formalize a guild in 1653. Together, they petitioned the viceroy to use the municipal ordinances to establish standards of production and distribution that would serve to control the trade. The ordinances outlined ten articles specifying requirements for guild membership, prerequisites for master potters, steps for processing clay and glaze mixtures, and the manner in which pieces were to be decorated. The three potters designated to lead the guild in 1653 were Diego Salvador Carreto, Damián Hernández, and Andrés de Haro. Carreto was appointed inspector, Hernández for white ware (diputado para lo blanco), and Haro for common or yellow ware (diputado por lo amarillo).11

To regulate production, the ordinances specified three types of pottery: cooking ware, common ware, and fine ware (loza amarilla, loza común, and loza fina). Later a refine ware (loza refina) was added, stipulating that it was reserved for blue-and-white Chinese-style decoration. Those who produced common ware could not produce fine ware unless they had passed an exam and were confirmed by the guild as a master potter.

The city was dominated by Spaniards, and thus, the ordinances decreed only men of pure Spanish parentage could be considered for the master potter examination. However, while the guild was largely controlled by Spaniards, there is adequate evidence to suggest that Indigenous, mestizo, and free and enslaved African men also contributed to production. Franciscan historian Jerónimo de Mendieta (1525–1604), in his book Historia eclesiástica indiana (1595), documents Indigenous expertise in pottery and their eventual mastery of glazing techniques introduced by Spanish craftsmen. He wrote:

[The Indigenous] were masters of pottery and clay hollowware for eating and drinking. Their pottery was finely painted and well made. And although they were not familiar with glazing, they learned this process later from the first masters who arrived from Spain, no matter how much he guarded and protected it from them.12

In 1579, Gerónimo Pérez de Salazar agreed to finance the opening of the ceramic workshop of Antonio Xinovés and “feed Xinovés, the other journeymen, and the Indians employed.”13 Other examples support the presence of Indigenous men employed by workshops; however, because they were barred from taking the exam required to become master potters, they were unable to move beyond the role of journeyman. Thus, regardless of proficiency, racial restrictions limited advancement for many potters. Mestizo potters were, however, ultimately permitted to rise to the rank of master potter, such as Francisco Martín, who had worked since 1666 on the street of Traje de la Santa Iglesia Catedral.14

One of the earliest documented potters in Puebla, Gaspar de Encinas (ca. 1537–1619), migrated from Seville, Spain, and established a workshop near the cathedral on Calle los Herreros. Born in Seville around 1537, Encinas married María Gaitan from Talavera de la Reina, and they had four sons before he departed for Mexico without his family between 1587 and 1590. Encinas had worked in Talavera de la Reina before moving to New Spain. In New Spain, Encinas produced ceramic tableware, water pipes, and likely the first glazed tiles. In 1602, he received a commission to produce tiles for the first cathedral of Mexico City.15

Mexican historian Guillermo Tovar de Teresa attributed to Encinas two rare basins with a lace design in monochrome manganese that he acquired from the Pérez de Salazar collection (one is illustrated in fig. 3).16 As the decoration likely originated in Talavera de la Reina, it was more likely Encinas’s son, Gaspar Encinas, el mozo, who introduced the lace design to Puebla as the style of decoration had not yet been developed before Encinas, el viejo, left for New Spain.17 Encinas, el mozo, came to Puebla from Talavera de la Reina with his mother at the very end of the sixteenth century, along with a number of supplies his father had requested.18 Once settled in Puebla, he continued the family tradition by becoming a master potter. A document from 1619 indicates that he and his second wife, Ursula de Espindola, lived on Calle los Mesones, where they kept a store.19

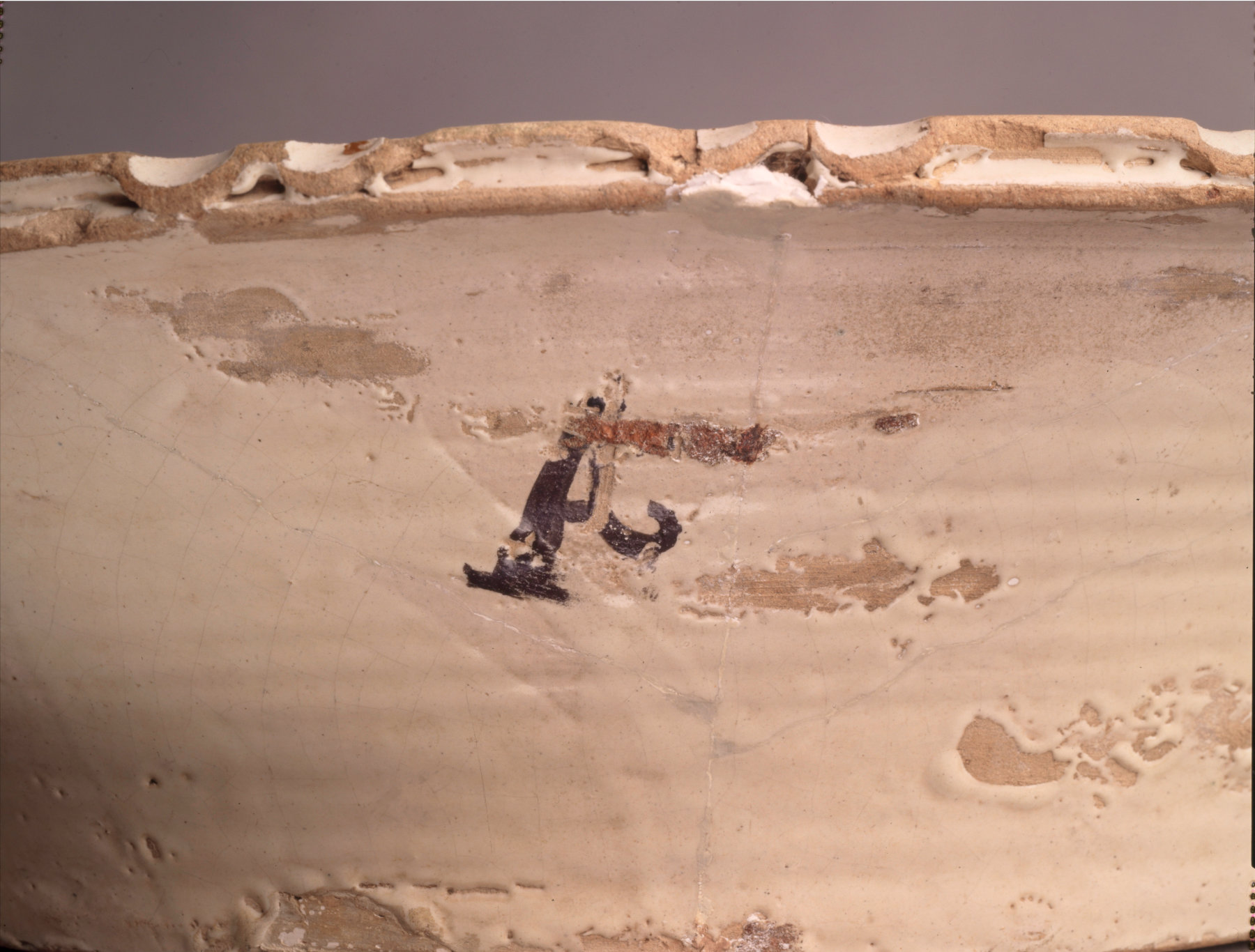

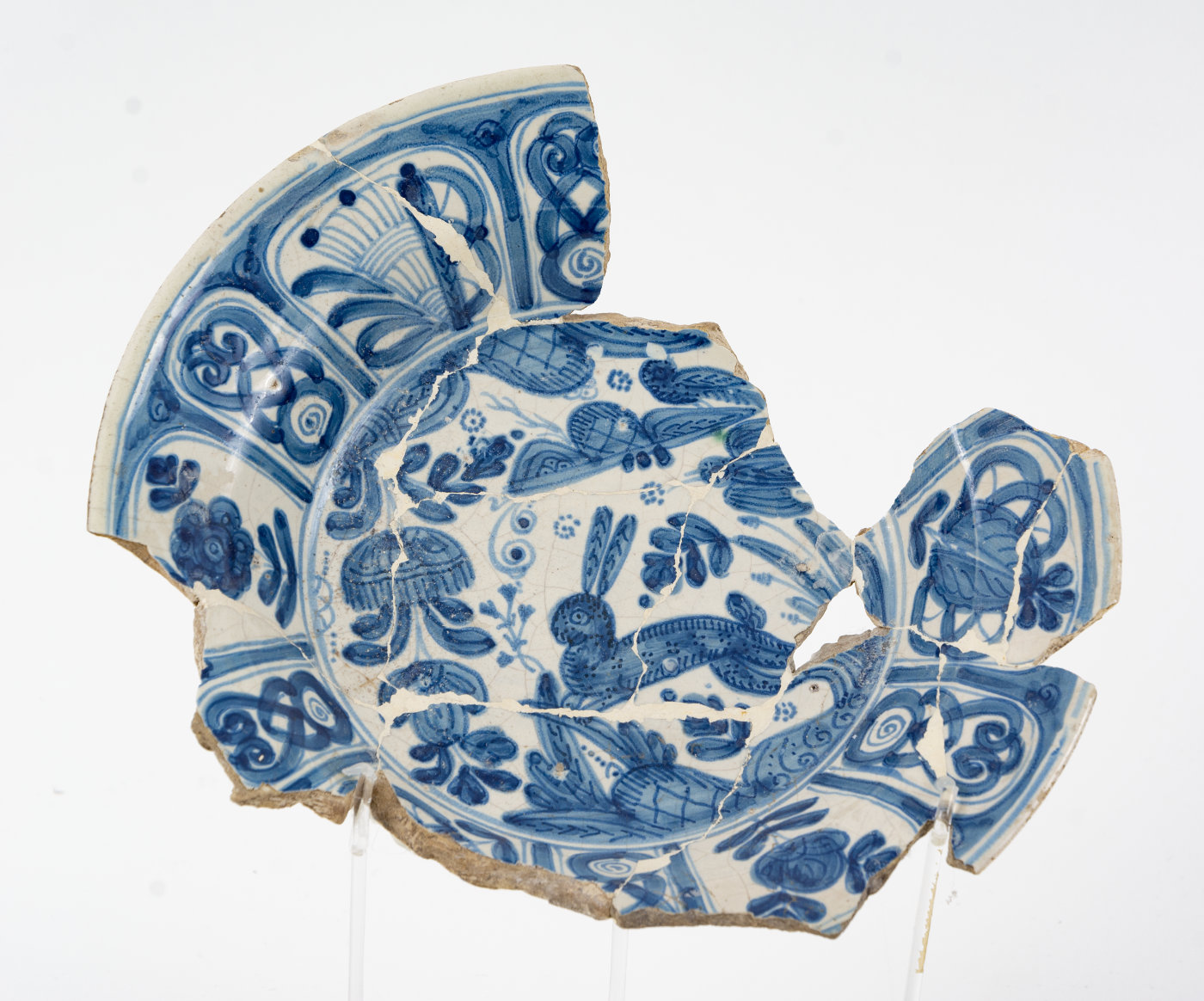

Despite the strong resemblance to the lace design from Talavera de la Reina, the decoration of the Puebla basin also evokes its local manufacture with an image of a guajolote (Mexican turkey) at the center.20 The lace decoration evolved significantly from its Spanish roots by the mid-seventeenth century, introducing cobalt and reimagined to create a web-like pattern. To archaeologists, this decoration is referred to as Puebla Polychrome, characterized by its cobalt-blue-and-manganese design.21 While intact pieces from the seventeenth century are rare, the number of fragments found in archaeological excavations in Central America, the Caribbean, Georgia, Florida, and New Mexico suggest that it enjoyed a wide appeal.22 A rare extant example from The Metropolitan Museum of Art includes an inscription: “I am for washing the purificators and nothing else” (Soy para labar los puryfycadores y no más), indicating that it was made for washing the altar napkin used to clean the chalice following communion (fig. 4). On the outer wall of the vessel appears the letter “A,” referencing a potter’s mark that was required by all master potters (fig. 5). Without the existence of a ledger or document correlating the mark to a specific potter or workshop, we must rely on the names we find in historic records that correspond to the dates identified by archaeologists, which for this design span from approximately 1650 to 1680. Using those dates, we may surmise that the mark “A” may be associated with the workshop of Domingo de Aguilar, Jose Anaya, or Antonio de Arteaga, all of whom were master potters from the early to mid-seventeenth century.23

The “A” mark also appears on another type of tin-glazed earthenware from Puebla known as Abo Polychrome, which has a distinct combination of orange, yellow, green, and manganese thin lines (fig. 6).24 Abo polychrome is likely the product of a stipulation in the potter ordinances that specifies “in order that there be variety, the other style of decoration for this fine ware shall be in imitation of Talavera [de la Reina] ware or figures and designs in colors shading them with all the five colors used in the art.”25 Given the strong correlation to the design tradition of Talavera de la Reina, we might assume that the potter who helped popularize it had worked in Talavera de la Reina or was familiar with the style. Figure 6 is one of the few extant examples. While it is unmarked, it is typical of many of the fragments found with a mark.

By the mid-seventeenth century, Puebla potters began responding to the increasing demand for vessels inspired by Asian designs as a result of transpacific trade between 1565 and 1815 that brought millions of goods from Manila to New Spain—an important topic covered by Diego Javier Luis in this volume.26 This shift likely took place prior to the issuance of amendments to the ordinances in 1682, one of which specified that one of the decorations shall be in “imitation of Chinese ware, very blue, finished in the same style.”27 A pair of identical blue-and-white jars marked “he” held by the Hispanic Society Museum & Library (fig. 7) and the Philadelphia Museum of Art represent two of the finest examples of how Puebla potters responded to the growing enthusiasm for Chinese style while also maintaining a unique style of their own. The mark “he” on the lower register has been attributed to master potter Damián Hernández. As a founding member of the potter’s guild and one of its first inspectors, the attribution is logical. Born in Spain, Hernández settled in Puebla at a young age and learned the art of tin-glazed earthenware in Mexico from Antonio de Vega y Córdoba. Hernández’s name appears in documents as early as 1607, which suggests that he was older and well-established professionally when he founded the guild with his colleagues.28 The use of blue and white, cloud forms, and male figures with queue hairstyle all characterize the Chinese style. However, the narrative scene better reflects the dramatic festivals that took place in Puebla and other cities, where individuals dressed in costumes from different parts of the world, bullfights took place, and triumphal chariots processed in a theatrical fashion. One such event occurred in 1649 on the occasion of the consecration of the cathedral of Puebla, when people “dressed as Spaniards and Indians of all nations . . . and performed cañas y toros (lance and bullfighting) all ending with the dramatic appearance of a triumphal chariot dedicated to the Immaculate Conception.”29

Whether the mark “he” represents Hernández, his workshop, or even another potter altogether, the number of sophisticated examples signed “he” suggest that the production was important.30 A basin from the Franz Mayer Museum (figs. 8 and 9) and a pharmacy jar from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (figs. 10 and 11) are among the wide variety of extant pieces marked “he.” The decoration of these and other works fully embraces another article in the 1682 amendment to the ordinances specifying that one decoration shall “be painted in the manner that we call aborronado,” a term used to describe blurred or blotted dots. The jar (fig. 10) is decorated with a density of decoration surrounding a rectangular void for a removeable label or inscription naming the medicinal contents of the jar. Woven within crowded blurred dots and foliage of the basin (fig. 8) appear a quetzal bird and feline, both important animals in Mesoamerican cosmology and iconography. It is not known if the image was requested as part of a commission or if it was a subject that the painter was familiar with. It does, however, suggest the influence of Mesoamerican imagery endured through the viceregal period. The use of local and Mesoamerican references appears in other vessels, such as the bird on a cactus popularized on blue-and-white jars from about 1700 (fig. 12) and ocelots found on blue-and-white tiles (fig. 13).31

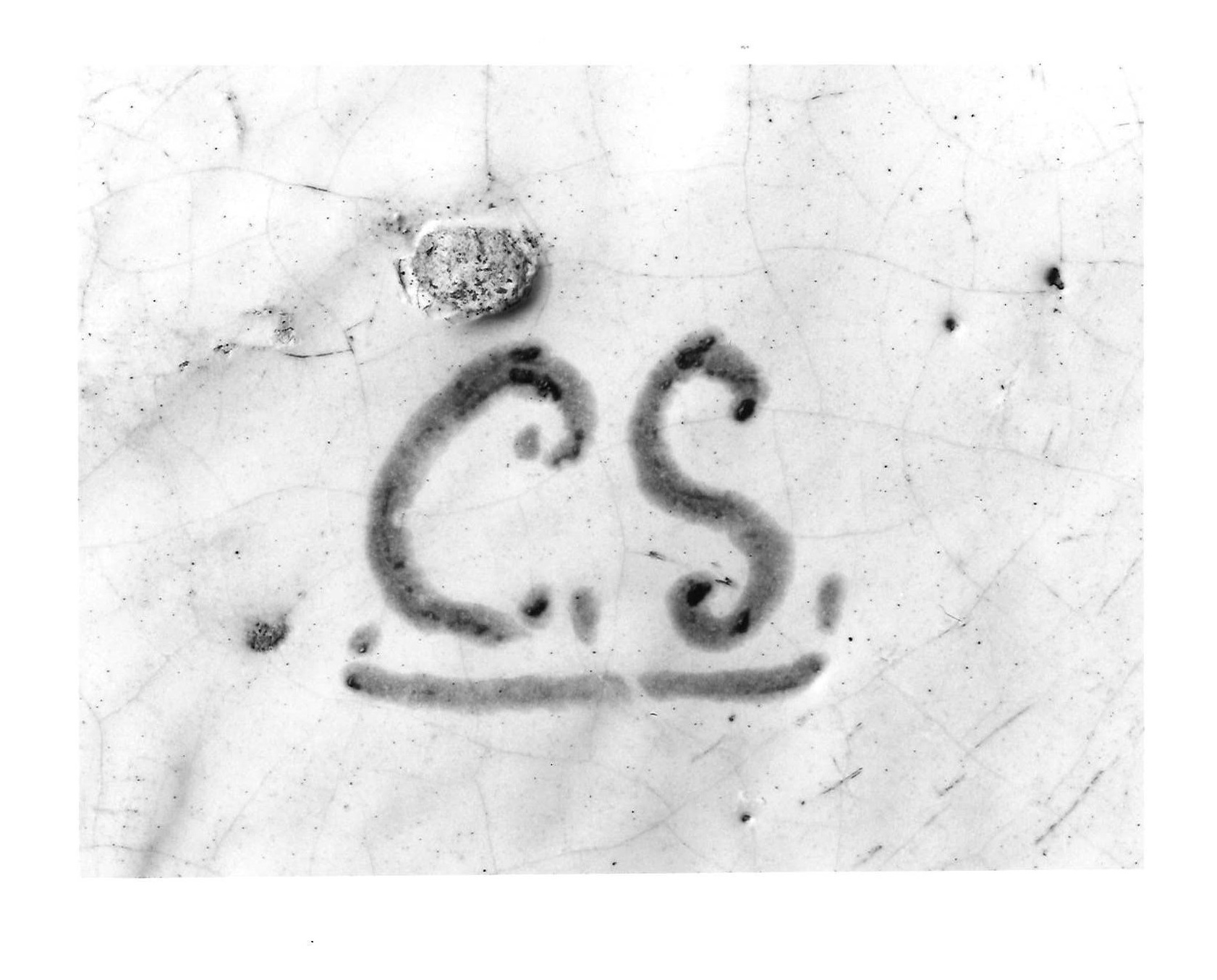

Of all the marks known today, “C.S.” is one found most frequently on blue-and-white Puebla pottery from the viceregal period (figs. 14 and 15). Edwin Atlee Barber, former director of the Philadelphia Museum and School of Industrial Art (present-day Philadelphia Museum of Art), attributed the mark to Diego Salvador Carreto, who was active in 1649 and died between 1670 and 1671, and like Hernández was one of the founders of the potters’ guild.32 While the attribution is a logical choice given the quality of the pieces and Carreto’s rank in the guild, the letters would then be in reverse order. In current practices, it is not uncommon for workshops to require painters of vessels to sign their initials in reverse, so it is possible that the tradition has been perpetuated over time; however, there is nothing to indicate that this was a common practice during the viceregal period. Another possible attribution is Cristobal Sánchez de Hinojosa, el viejo, who was a master potter documented in 1653.33 The C.S. mark appears on a wide variety of pieces that span from the mid-seventeenth century through the eighteenth century, which supports the idea that the mark represents a family workshop that continued to use it for generations.

The letter “F” is another important mark found on vessels and a series of tiles representing different trades (see fig. 13). These tiles are among the most finely painted works produced in Puebla during the seventeenth century. Not all the tiles from the series have the “F” mark, although the frequency of the mark and the repetition of the scenes suggest that these were produced at the same workshop. There are a number of artists from the last quarter of the seventeenth century whose names contain the letter “F,” such as Juan de la Feria, Luis Fernández Lechuga, and Miguel Fernández Palomino. While the decoration of the tiles is entirely unique, they resemble the style of decoration found in Kraak porcelain from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644)—a style that became increasingly popular among Puebla workshops by the turn of the eighteenth century. An excellent example of this type of design was uncovered from a site excavated during the renovation of the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City (fig. 16).

Master potter Diego de Santa Cruz de Oyanguren y Espinola (also spelled Espindola) was considered one of the most important producers of tin-glazed earthenware during the eighteenth century. Espinola was appointed alcalde of the guild numerous times between 1734 and 1761.34 He was married to Maria de Zayas, whose family had operated a prominent ceramic workshop in Puebla since the seventeenth century (and was mentioned earlier in the text). Like his wife’s family, Espinola became so well known that the street where the workshop was located carried the family name of “street of Espinola” (calle de Espinola). The lawyer to the Royal Audience, Manuel Caro, presented Espinola to the viceroy in 1762 as having “invented” the Chinese style in Puebla.35 He continued to promote Espinola by boasting that “most experts were not able to distinguish his work from that of China or Japan” and that his ware was “not only the most polished but also the most durable.”36 Depending on how one defines the “Chinese style,” it is unlikely that Espinola invented it in Puebla; however, he and his workshop certainly may have specialized in the decoration. A late-eighteenth-century or early-nineteenth-century plate signed “Espindola” on the back suggests that the workshop was in operation for multiple generations.37

In 1813, a new constitution for the Spanish empire, promulgated by an anti-monarchical assembly at Cádiz, eradicated the potter’s guild and revoked the ordinances. Mexican ceramicists were free to create new styles of their own, but the lack of regulations led to a decline in the quality for which Puebla potters were known. Also at this time, workshops in other parts of Mexico began producing less expensive alternatives. The lifting of import restrictions allowed for a variety of European ceramic types to enter New Spain. The demand for Asian-style pottery declined alongside the weakening of transpacific trade, which ultimately ended in 1815, just as independence movements were emerging in the Americas.

Despite numerous attempts by the guild to require master potters to mark their work, most of the extant viceregal vessels remain without a mark, leaving much of Puebla’s ceramic history anonymous. This may have been the result of market constraints during the viceregal period as the demand for ceramic ware grew and the guild’s rigid regulations became increasingly difficult to enforce, particularly concerning the exclusive right of master potters to use costly cobalt blue.

The success of Puebla’s ceramic production beginning in the viceregal period is a testament to the city’s role as a major center of artistic and commercial exchange. While the potters’ guild established strict regulations to maintain quality and control production, the anonymity of many artisans—due in part to social hierarchies and guild restrictions—has left gaps in our understanding of individual contributions. The marks that do exist provide crucial insights into the workshops and stylistic evolution of Puebla’s ceramics, but they represent only a fraction of the story. For example, marks are typically signed by the painter of the vessels and most workshops involve specialists for each area of production. The dissolution of the guild in the early nineteenth century led to both artistic liberation and a decline in the standardized quality that had defined Puebla pottery for centuries. Nevertheless, the tradition adapted and endured. The revival efforts of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—with potters such as Ysauro Uriarte Martínez, Enrique Luis Ventosa, J. Miguel Martínez, Antonio Espinosa, and Pedro Padierna—had a lasting impact on the regrowth of the industry and development into new directions that would ultimately lead to the enforcement of new authenticity standards and establishment of the trademark of the term “talavera.” By reassessing the historical record and recognizing the collaborative nature of these workshops, we gain a deeper appreciation for the artistry, labor, and cultural significance embedded in Puebla’s famed pottery. Today, potters continue to draw inspiration from historical forms while innovating within the medium to create unique works of art. This has ensured that the legacy of Puebla’s potters remains a vital part of the city’s heritage.

Notes

-

This tradition takes its name from Talavera de la Reina, a city in central Spain where many of Puebla’s first potters originated. The term talavera eventually became synonymous for the glazed pottery by 1824 when Ysauro Uriarte opened his workshop as Fabrica de Loza de Talavera. ↩︎

-

Examples of the prehispanic pottery known as Cholula ware or Mixteca-Puebla ware can be found at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City and Amparo Museum in Puebla, among other museums. For example, see the pedestal bowl in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, 1979.206.365, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/312587. ↩︎

-

Florence C. Lister and Robert H. Lister, Sixteenth Century Maiolica Pottery in the Valley of Mexico (University of Arizona Press, 1982), 89. ↩︎

-

Hugo Leicht, Las Calles de Puebla: Estudio Historico (Junta de Majoramiento Moral, Civico y Material del Municipio de Puebla, 1986), 412; Margaret E. Connors McQuade, “Loza Poblana: The Emergence of a Mexican Ceramic Tradition” (Ph.D. diss., City University of New York, 2005), 77. ↩︎

-

Enrique Cervantes, Loza Blanca y Azulejo de Puebla, 2 vols. (Puebla de los Ángeles: Privately printed, 1939), 1:112–19. ↩︎

-

“En la calle que va de la Plaza Pública a la iglesia del Evangeslista San Marcos.” Ibid, 2:185. This and all translations are by the author. ↩︎

-

McQuade, “Loza Poblana,” 70–71. ↩︎

-

Sagrario Angelopolitano, Puebla, Libros de Matrimonio, March 11, 1674. Cited in Cervantes, Loza Blanca, 2:238. ↩︎

-

Cervantes, Loza Blanca, 2:324–25. ↩︎

-

Archivo Histórico Municipal de Puebla (AHMP), December 5, 1573, Libro de Actas de Cabildos, no. 10, fol. 118. ↩︎

-

Cervantes, Loza Blanca, 2:174. ↩︎

-

Jerónimo de Mendieta, Historia eclesiástica indiana (Editorial Porrúa, 1980), 4:404. ↩︎

-

Agreement between Antonio Xinovés and Gerónimo Pérez de Salazar, 1579. Collection of Francisco Pérez de Salazar, Mexico City. I am grateful to Mr. Francisco Pérez de Salazar for providing this document and his support of my research. ↩︎

-

AGNP, 1666, fojo 1399. Cited in Cervantes, Loza Blanca, 2:218. ↩︎

-

Archivo de la Catedral de Puebla, Fábrica Municipal, Legajo II. Cited in Cervantes, Loza Blanca, 2:15; Lister and Lister, Sixteenth Century Maiolica, 231; Rose Gpe. de la Peña V., “Azulejos encontrados in situ: primera catedral de México,” in Ensayos de Alfareria Prehispánica e Histórica de Mesoamérica: Homenaje a Eduardo Noguera Auza, Serie Antropológia 82, ed. Mari Carmen Serra Puche and Carlos Navarrete Cáceres (Universidad Autónoma de Mexico, 1988), 437–38. ↩︎

-

The attribution was suggested to me via email in late 2018 by Guillermo Tovar de Teresa, who acquired the pieces from the Pérez de Salazar family. The basins are currently held in the Guillermo de Tovar House Museum, operated by the Museo Soumaya in Mexico City. ↩︎

-

See, for example, Alfonso Pleguezuelo, “Center of Traditional Spanish Mayólica,” in Cerámica y Cultura: The Story of Spanish and Mexican Mayólica, ed. Robin Farwell Gavin, Donna Pierce, and Alfonso Peguezuelo (University of New Mexico Press, 2003), pl. 1.11. ↩︎

-

Archivo General de las Indias, Seville (AGI), “Gaspar de Encinas a su mujer Maria Gaitán en Triana,” April 30, 1596 (Puebla), Indiferentes. Cited in McQuade, “Loza Poblana,” 57. ↩︎

-

AGNP, Notaria no. 4, Protocolos de 1619, folios 183–186r. It is worth noting that Espindola is another important family name among ceramic workshops in Puebla who continued the tradition into the nineteenth century. ↩︎

-

See Donna Pierce’s entry in Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries, exh. cat. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990), 461. ↩︎

-

John M. Goggin, Spanish Majolica in the New World: Types of the Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries (Yale University Press, 1968), 173. ↩︎

-

Kathleen Deagan, Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies of Florida and the Caribbean, 1500–1800 (Smithsonian Institute Press, 1987), 83–84. ↩︎

-

Cervantes, Loza Blanca, 2:199–200. ↩︎

-

Lister and Lister, Sixteenth Century Maiolica, 241. ↩︎

-

Cervantes, Loza Blanca, 1:28–29. ↩︎

-

See also Diego Javier Luis, The First Asians in the Americas: A Transpacific History (Harvard University Press, 2024). ↩︎

-

Cervantes, Loza Blanca, 1:29; McQuade, “Loza Poblana,” 148. ↩︎

-

Cervantes, Loza Blanca, 1:112, 114, 116, 118. See also Margaret E. Connors McQuade’s entries in The Arts in Latin America, 1492–1820, ed. Joseph J. Rishel and Suzanne L. Stratton-Pruitt, exh. cat. (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2006), 140–41. ↩︎

-

Antonio Tamariz de Carmona, Relación y descripción del templo real de la ciudad de Puebla de los Ángeles en la Nueva España y su catedral: Que de orden de su magestad acabó y consagró a 18 de abril de 1649 (Puebla de los Ángeles, s.n.). ↩︎

-

Examples can be found at the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City, José Luis Bello y González Museum in Puebla, Soumaya Museum in Mexico City (formerly from the collection of the Pérez de Salazar family), as well as The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Hispanic Society Museum & Library in New York, among others. ↩︎

-

I am grateful to Roberto Junco of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia in Mexico City for bringing this to my attention. ↩︎

-

Edwin Atlee Barber, The Maiolica of Mexico (Art Handbook of the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art) (Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, 1908), 50. ↩︎

-

Cervantes, Loza Blanca, 2:229. ↩︎

-

Ibid, 2:303–04. ↩︎

-

Ibid, 1:42. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid, 2:190–91. ↩︎