Acapulco is a famous vacation destination today, especially for people from Mexico City. Its appeal began in the 1950s, when Hollywood actors and the international jet set flocked to its sunny shores. However, relatively few people outside academic circles know about the Acapulco–Manila Galleon trade route and the renowned Acapulco Fair, where silver from the Americas traded for a wide range of luxurious and exotic goods from across the ocean. Although Acapulco was a small port until the second half of the twentieth century, it was a nodal point in sixteenth- to early nineteenth-century global commerce. First, it was the designated American port for the Acapulco–Manila route (the name depending on whether the ship was sailing to or from Manila or Acapulco), bridging both sides of the Pacific. Second, it was also connected to the ports of Panama and Callao, Peru, with merchants arriving with South American silver. Mexico City was a short way from Acapulco, connecting to Puebla, Veracruz, and then on to the Atlantic and Caribbean.

Much archaeological research has been undertaken in the last decade, feeding into what can be called an “archaeology of the Manila Galleon.” The most significant body of work concentrates on ceramics, including style, provenance, distribution, and consumption studies. For many years, archaeological evidence from different shipwrecks and excavations has contributed to our understanding of transpacific trade. Archaeological work has revealed production centers and even specific kiln sites, as well as studies of porcelain commercialization, use, and influence in Mexico and Manila, among others.1 Since 2015, archaeological excavations at Acapulco have yielded an interesting collection of porcelain. This brings to light new evidence about the port’s commercial activity and a better understanding of the types of pieces available for commercialization in New Spain and beyond. Some of the sherds tell individual stories and contribute to our understanding of the early modern world and the Manila Galleon.

Acapulco

Designated in 1573 as the official origin and terminus of the Acapulco–Manila Galleon route, Acapulco’s well-protected harbor became the entry and exit point for galleons traveling along this crucial commercial route for over 250 years. In 1565, the first galleon, the San Pedro, under the direction of fray Andrés de Urdaneta, discovered the tornaviaje, or return route, from the Philippines, following the northern Pacific currents to the American continent and then sailing south to reach Acapulco. This development made it possible to establish a continuous connection between Acapulco and Manila. Manila itself was part of a preexisting network of Asian commercial routes. The Spanish Crown protected this trade route from competing interests, such as the merchants from Seville or Lima. Under the direction of the Casa de la Contratación, the merchants of Mexico controlled the trade, fighting with the irregular Peruvian ships and merchants that made the voyage yearly for the best products and prices. Taxation on imported products helped finance the administration of the Philippines and supported the Church in the islands. Historical accounts mention the luxurious items that passed through Acapulco, including silks, cotton, and other textiles from India, China, and the Philippines; spices and precious woods from Southeast Asia; lacquerware and screens from Japan; and ceramics from China.

Several historical figures testify that Acapulco was an ideal port, as William Lytle Schurz pointed out in his famous 1939 book on the Manila Galleon:

Domingo Fernández de Navarrete, a much-traveled friar, called it “the best and safest harbor in the world, as was duly asserted by those who have seen many others.” Of the size of the harbor Dampier remarks: “The Port of Acapulco is very commodious for the reception of Ships, and so large, that some hundreds may safely Ride there without damnifying each other.” Lord Anson considered it “the securest and finest in all the northern parts of the Pacific Ocean.” Malaspina, one of the most skilled of Spanish navigators of the later eighteenth century, a scientific seaman of the type of Cook and Bougainville, favored the further development of Acapulco as a Spanish naval base for the northern Pacific and a great commercial port. He thought it much superior to San Blas. “No one can deny,” he said, “that Acapulco has great advantages which are found together in very few ports of the globe.” Humboldt, who saw the place in 1803, thus describes the harbor, which he called “the finest of all those on the coast of the great ocean,” and again “one of the finest ports in the known world:” “The port of Acapulco forms an immense basin cut in granite rocks.”2

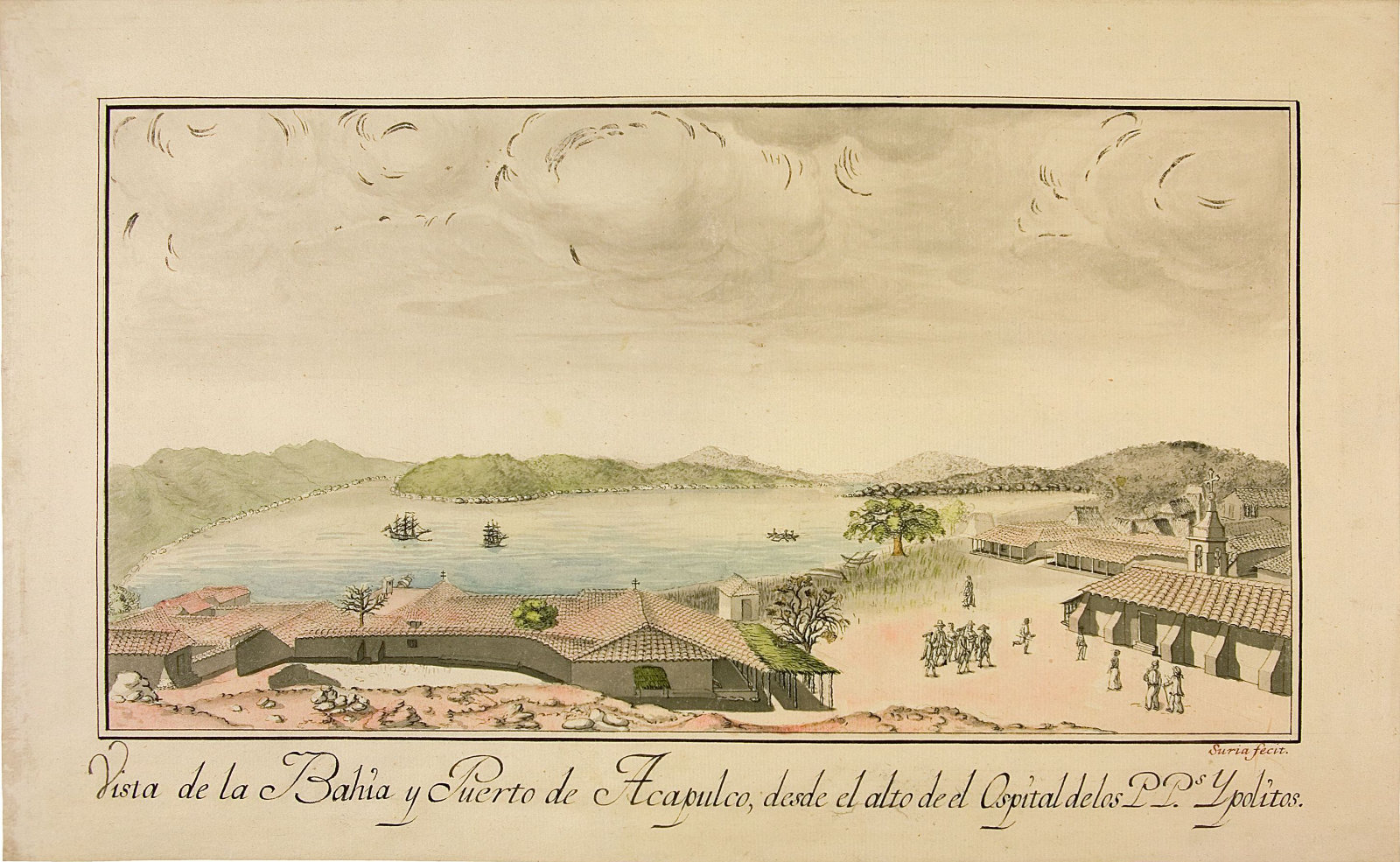

Despite the galleons, the annual fair, and the arrival of Peruvian ships and merchants from the interior, Acapulco remained modest throughout its historical period (fig. 1). Its most prominent structure was the Fort of San Diego. Other notable buildings included the cathedral church, a Franciscan convent, the San Juan de Dios Hospital, and the Royal Contaduría. None of them were significant or strongly built. In 1598, some 250 tiny houses existed, made of wood, adobe, and palm. The hot climate, the mosquitos and animals, and the lack of food, among other reasons, made it hellish for a population to develop. Many accounts from travelers and administrators attest to this.3

In 1578, fear spread through New Spain as it became known that Francis Drake passed northward through the viceroyalty, attacking the town of Huatulco. The same happened when Thomas Cavendish, in 1587, captured the galleon Santa Ana at the tip of Baja California. However, it was the Dutch attack on Acapulco in 1615 by Joris van Spilbergen that prompted the viceroy, Diego Fernández de Córdoba, 1st Marquess of Guadalcázar, to commission the construction of a new redoubt from the engineer Adrian Boot, who oversaw the drainage works in Mexico City. However, the viceroy rejected the initial proposal because it was small and insufficient. Boot then sent a fortification project consisting of five towers joined together with projections to give a pentagonal shape, which was approved. Work started in 1616, on top of a promontory dominating the bay to prevent attacks by pirates and enemies of the Crown who entered the bay. It was completed by February 1617. The fortress remained impregnable throughout the colonial period, except for a brief attack by Dutch pirates in 1624. However, a severe earthquake on April 2, 1776, caused substantial damage, leading to reconstruction efforts that commenced in 1778 and concluded in 1783. The rebuilt fortress, made of stone and surrounded by a moat, could accommodate up to two thousand people with ample provisions for a year. Initiated in 1810, the independence movement in Mexico became interested in capturing Acapulco. General José María Morelos sieged the Fort of San Diego for two years. The War of Independence ended the route; the last ship sailed off into the Pacific in 1815, ending a long, prosperous line. Acapulco remained sleepy until new opportunities came in the form of tourism and it regained its celebrated name.

Manila Galleon Archaeology

The archaeological interest in the colonial period of Acapulco arose from broader interest in the archaeology of the Manila Galleon, a theme and an approach that explores all aspects of the galleons, such as infrastructure, maritime and nautical aspects, trade, cultural influences, distribution, etc. and which has been developing through several papers and archaeological interventions over time.4 As José Luis Gasch-Tomás has noted: “Unfortunately, the archaeological studies of the Manila galleons have not developed as much as their histories. Apart from a few excavated underwater sites and several studies of the material culture transported in the galleons, especially Chinese porcelain and to a lesser extent Chinese silk and Japanese furniture, experts have undertaken few archaeological researches of the Manila galleons.”5 Among the few projects focused on shipwrecks recently conducted are the search for the galleon San Francisco in Japan by archaeologist Jun Kimura and several in the Philippines by Bobby Orillaneda and his team.6

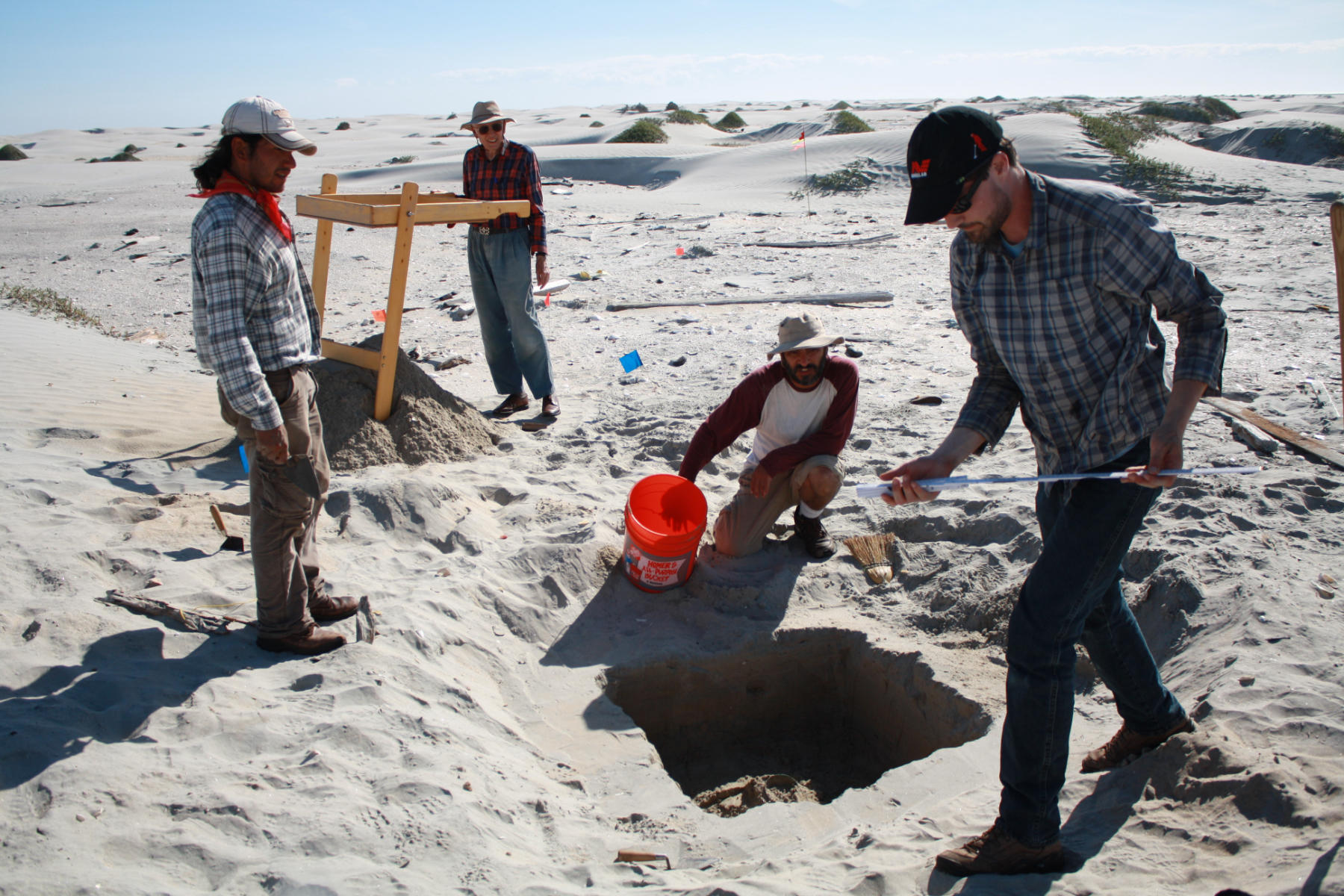

In 2000, the Underwater Archaeology Office (SAS) of the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico (INAH) began researching the remains of a sixteenth-century Manila galleon, wrecked on the journey from the Philippines to New Spain, on the coast of Baja California at the 38th parallel. This desolate, desert-like region by the ocean holds remains of the ship’s cargo scattered along eleven kilometers of the shoreline. A reference to the shipwreck site appeared in George Kuwayama’s Chinese Ceramics in Colonial Mexico (1997).7 His book presented images of Chinese porcelain sherds from an “unpublished site off the Baja California coast.” This citation aroused the interest of maritime historian Edward Von der Porten, who contacted him for more information. Kuwayama revealed that beachcombers had collected porcelain sherds from the site. In 1999, with this knowledge and under the supervision of INAH, Von der Porten, along with archaeologists Jack Hunter and Edward Ritter, organized the first expedition to the site thanks to the beachcombers’ information (fig. 2). SAS-INAH subsequently established the archaeological project “Manila Galleon, Baja California,” providing financial support for ongoing excavations, conservation, and research until Von der Porten’s passing in 2019. To date, 3,787 artifacts have been documented at the site, with extensive finds from the Chinese Wanli period (1573–1620), totaling 1,923 pieces. The collection primarily includes underglaze blue-and-white plates, bowls, cups, bottles, and boxes, alongside polychrome pieces studied by Von der Porten. The porcelain was manufactured in Jingdezhen (Jiangxi province) and Zhangzhou (Fujian province), and it significantly resembles the pieces from the sunken Chinese vessel Nan’ao 1, thought to have been en route to Manila in the early stages of the trade route.8 Additionally, at least five different types of stoneware sherds and complete pieces from southern China and Southeast Asia (possibly northern Vietnam) have been identified and were likely used as containers during the voyage. Other significant finds include fragments of Spanish olive jars, cloisonné plates, Mexican silver coins, a Chinese coin, small lead objects, pieces of beeswax, lead shot, metal fittings, a bronze incense burner cover shaped like a Fu dog, and compass gimbals.9 These artifacts provide crucial insights into the cargo carried aboard the galleons and the ship construction technology of that era.10

In 2006, an archaeological survey along the north coast of the state of Guerrero indicated possible smuggling activities related to the Manila Galleon route. Ming dynasty (1368–1644) porcelain sherds and a type of maiolica known as Romita Sgraffito were recorded. Around the same time, neutron activation analysis revealed this type of slipware was made in the region of the lakes of Michoacán. Therefore, the hypothesis is that some smuggled porcelain was destined for this region as part of an exchange route not documented in the historical record, revealing that not all Asian merchandise arrived in Acapulco before traveling to Mexico City as was the norm. Alternative, lesser-known routes were utilized for trade. The coastal area of Petatlán, to the north, was ideal for ships to anchor and load water, facilitating the unloading of select cargo items.11

In 2016 and 2017, SAS-INAH conducted an archaeological inspection of the Port of San Blas on the Pacific coast of Mexico, which yielded a collection of Chinese porcelain sherds linked to the transpacific trade (fig. 3). Although officially active only for a few decades in the eighteenth century, this port served as a stop along the Manila Galleon route. The predominant type of porcelain in the collection is landscape designs produced in Jingdezhen, which later developed into the “willow pattern.” The second most common type is blue-and-white Jingdezhen porcelain, followed by red-overglaze bowls known as Guanzai, dated from the mid-seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, indicating a continued movement of Asian goods even prior to San Blas’s establishment as a maritime department. As Gasch-Tomás mentions, “Remains of shipwrecks and Chinese porcelain are becoming as important as archival documents to write the history of the Manila galleons.”12 Indeed, porcelain has been archaeologically reported in the past in Mexico as elsewhere by authors like Goggin, Lister and Lister, López Cervantes, Pierson, and Fournier, among others.13 A distribution map showing archaeological finds of these ceramics was published in 2019 by Fournier and Junco.14 Many noteworthy archaeological works have been published since, some about specific sites like the kilns in China, new wrecks found in the Philippines, and ports and cities along the route. It would be another type of undertaking to be able to cite them all, but allow me to highlight some notable contributions, such as the work of Guanyu Wang, who characterized the porcelain traded by the Manila Galleon in the early part of the trade, during the Ming dynasty, describing three key moments.15 In the same book, Nida Cuevas writes about Fujian and Hizen wares found in the Philippines, Tai-Kang Lu addresses Kraak pieces from Macau and Taiwan linked to the Manila Galleon, and Etsuko Miyata describes the ceramics at Nagasaki and their relation to the Galleon.16 Archaeology is in an interesting position from which to study not simply the design, distribution, and evolution of porcelain but also the preferences of consumers. Furthermore, symbolic aspects (as mentioned in the work of Skowronek) and stylistic influences on Mexican ceramics from the imported Chinese porcelain appear in shape, color, and style (as in the work of Castillo and Fournier).17 It also allows us to reconstruct lesser-known aspects of the past, such as in San Blas, where porcelain reveals smuggling routes, which by nature are little documented, or as in Acapulco, where the distribution of porcelain permits us to make inferences on the location of the fair and where the galleon was unloaded. In recent years, a vibrant study of these topics has emerged and will contribute significantly to understanding the Manila Galleon from a material perspective.

Manila Galleon Archaeology in Acapulco

Historically, archaeological research in Acapulco has primarily focused on prehispanic remains around the bay. The area is home to various recorded archaeological sites, petroglyphs, and ceramic artifacts, some of which are among the oldest ceramics in Mesoamerica.18 However, little attention had been given to the colonial period, and no materials were reported until 2015. That year, excavations at the Fort of San Diego uncovered enough evidence to initiate a long-overdue project focused on the colonial period (fig. 4). In 2015, the SAS-INAH responded to a report in Acapulco Bay and documented some historical objects that divers retrieved from the water. Also, excavations in Acapulco commenced as a rescue effort linked to maintenance work on the outer wall of the San Diego fortress, which is now the History Museum of Acapulco, recovering archaeological materials from the prehispanic, early contact, colonial, and republican periods. This excavation found various materials such as ceramics, metal, glass, stone, and bone. Among the ceramics are sherds of prehispanic and local wares, Spanish olive jars, Chinese porcelain, English transfer-printed pottery, and Asian stoneware. Archaeological research focusing on the colonial period in Acapulco has led to the developmente of a comprehensive project that includes underwater and land investigations at the port, the “Proyecto de Arqueología Marítima del Puerto de Acapulco” (PAMPA, or Maritime Archaeology Project at the Port of Acapulco), which aims to reconstruct historic Acapulco’s maritime activity. One of the main goals of PAMPA is to understand the relationship between archaeological materials and trade dynamics over time, examining how these evolved and changed. Since Acapulco was the gateway between New Spain and the Pacific Ocean, investigating the archaeological remains at the port is key to understanding commercial dynamics of the colonial period. The project also involves documenting shipwrecks and the remains of vessels to catalog all historical elements found within the bay. The project employs a variety of theoretical approaches, including historical archaeology and maritime archaeology, to interpret these findings.

A second archaeological excavation took place in downtown Acapulco in 2016, where the local government initiated a thirty-meter-long ditch for a water system replacement adjacent to the Cathedral on Francisco I. Madero, La Paz, and José María Iglesias streets. This two-meter-deep ditch unveiled thousands of blue-and-white porcelain fragments, primarily of the Kraak porcelain style produced in various private kilns in Jingdezhen. Given the site’s central location, it is hypothesized that it may have been where the traditional Acapulco Fair was hosted annually just after the arrival of the Manila Galleon every December or January. The similarities in motifs on the porcelain sherds and their size suggest that many pieces sustained damage during the long five- to six-month voyage from Asia to Acapulco, with some items likely breaking en route and being discarded upon arrival.19 Three test pits on the slopes of Fort San Diego were excavated. Many materials were recovered during this season, including over five thousand pieces of Chinese porcelain, mainly from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

In 2017, further archaeological rescue was conducted in the town center, focusing on several streets, especially parts of La Quebrada street. In 2018, excavations were carried out at Fort San Diego, with four excavation units recovering material and documenting an architectural element before a section of the fort wall. In 2019, restoration work was performed on the mentioned part of the old fort, and it was reburied. This project has recovered over ten thousand colonial-period artifacts, including Chinese porcelains, maiolica and colonial ceramics, English earthenware, metal artifacts, and glass.

In the 2020 season, activities were proposed related to the organization of the information generated, as well as documentary research efforts, highlighting access to digital collections for the creation of a digital and physical library of maps and plans of the port of Acapulco and Fort San Diego from the colonial era. Additionally, dissemination talks were planned for primary schools and carried out remotely. Once normal post-pandemic activities resumed in 2023, office work focused on analysis of the recovered porcelain collection and creating a database for information and consultation. Finally, in 2024, along with Dr. Ivan Valdéz of UNAM, we curated the restructuring of the museography content at Fort San Diego, displaying some of the pieces recovered from the excavations conducted there (fig. 5).

An Ocean of Blue and White

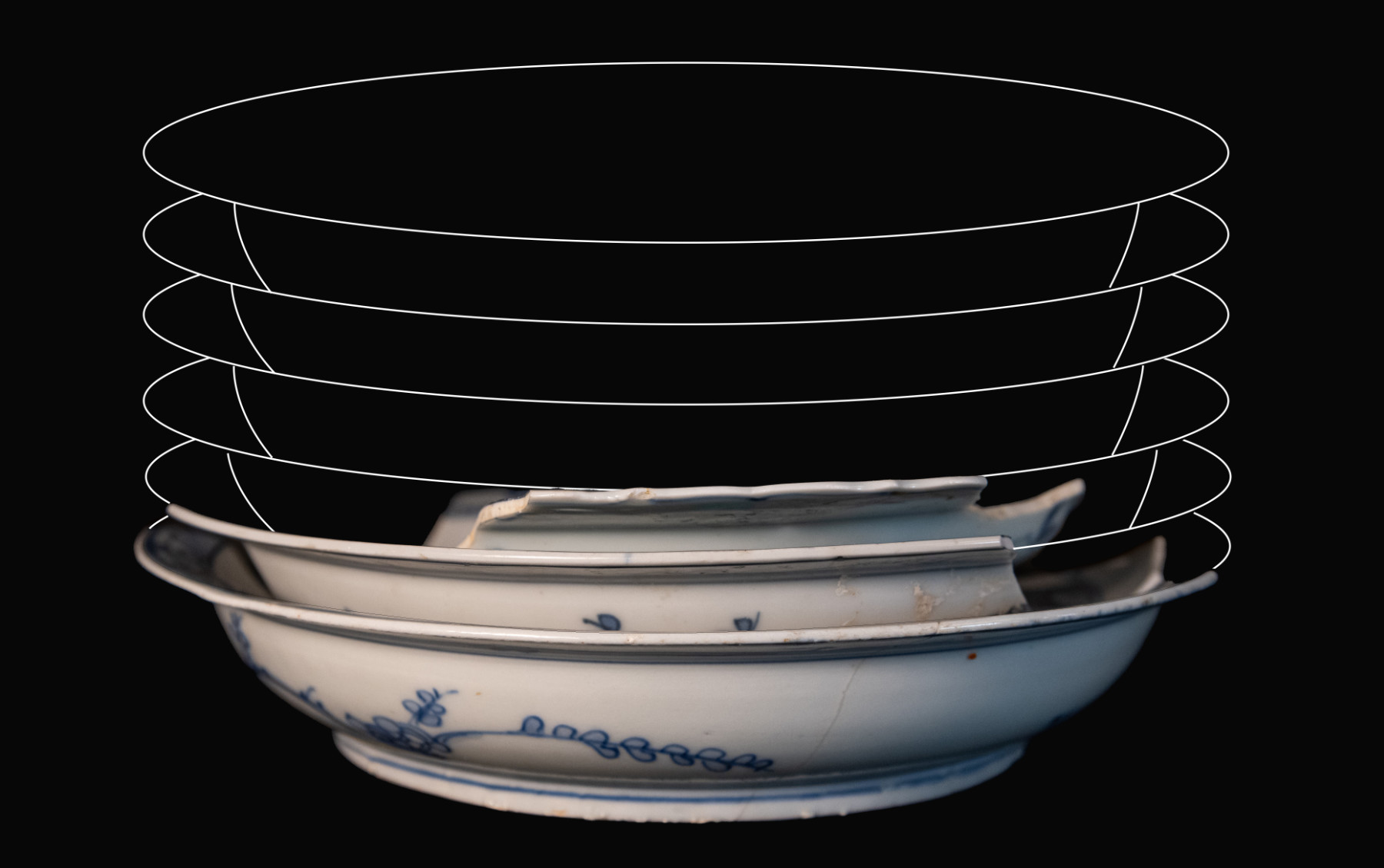

While Chinese porcelain had not been previously documented archaeologically in Acapulco, the more than 6,500 fragments identified to date are noteworthy. Preliminary analysis indicates that, within the fortress, most of the porcelain dates to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, whereas the porcelain found in downtown Acapulco belongs to the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries; some of the sherds appear to be from very early in the route, the 1560s and 1570s. This discrepancy can be attributed to the fortress’s destruction during an earthquake in 1766, followed by its reconstruction. In contrast, the downtown area, where more than 90 percent of all porcelain was recovered, mainly from the Wanli period (1573–1620) of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), may well be the site of the cargo offloading, the area for opening containers, and where the Acapulco Fair was held annually. Some of the pieces in the collection point to this fact. For example, over a dozen fragments of a delicate plate representing deer in the park from the Ming dynasty can be said to have come from the same hand (fig. 6). When we overlap the fragments, we see they are almost identical in the paintwork. As with a puzzle, the fragments that could not be joined belong to at least four plates, maybe six or more. Having been made and packed in Jingdezhen, they traveled to the coast, sailed to Manila, then sailed to Mexico, and arrived partially broken in Acapulco (fig. 7). They were likely discarded in the same place where the unpacking was done during the Acapulco Fair. A dozen plates were bundled together, and a few cracked. Whatever the fact, they are also important as they are the finest example of a considerable number of plates with a deer-in-the-park design. There is also a plate from around the same period from Zhangzhou, somewhat reconstructed, and it has a lower-quality design of a deer in the park in the collection (fig. 8).20 This comparison gives us a range of what the consumers in New Spain acquired.

As mentioned, there is a large quantity of this motif in plates, bowls, and large vessels.21 As with the plates mentioned earlier, around two dozen fragments of large bowls with deer (ca. 1580–95) suggest items discarded when unpacked (fig. 9). Although the deer are not identical in all (some are), they are the same shape and design with slight variations; for instance, the dotting in the deer is sometimes in clusters of four and in other instances is in lines. The interior base presents, in all but one, a rabbit. A few small bowls also repeat the deer motif in a smaller version. The same thing occurs with the typical cups decorated with a crow motif (ca. 1590–1600). There are a dozen bases with this motif, with slight variations of the bird in the interior bottom of the cup and the exterior decoration.

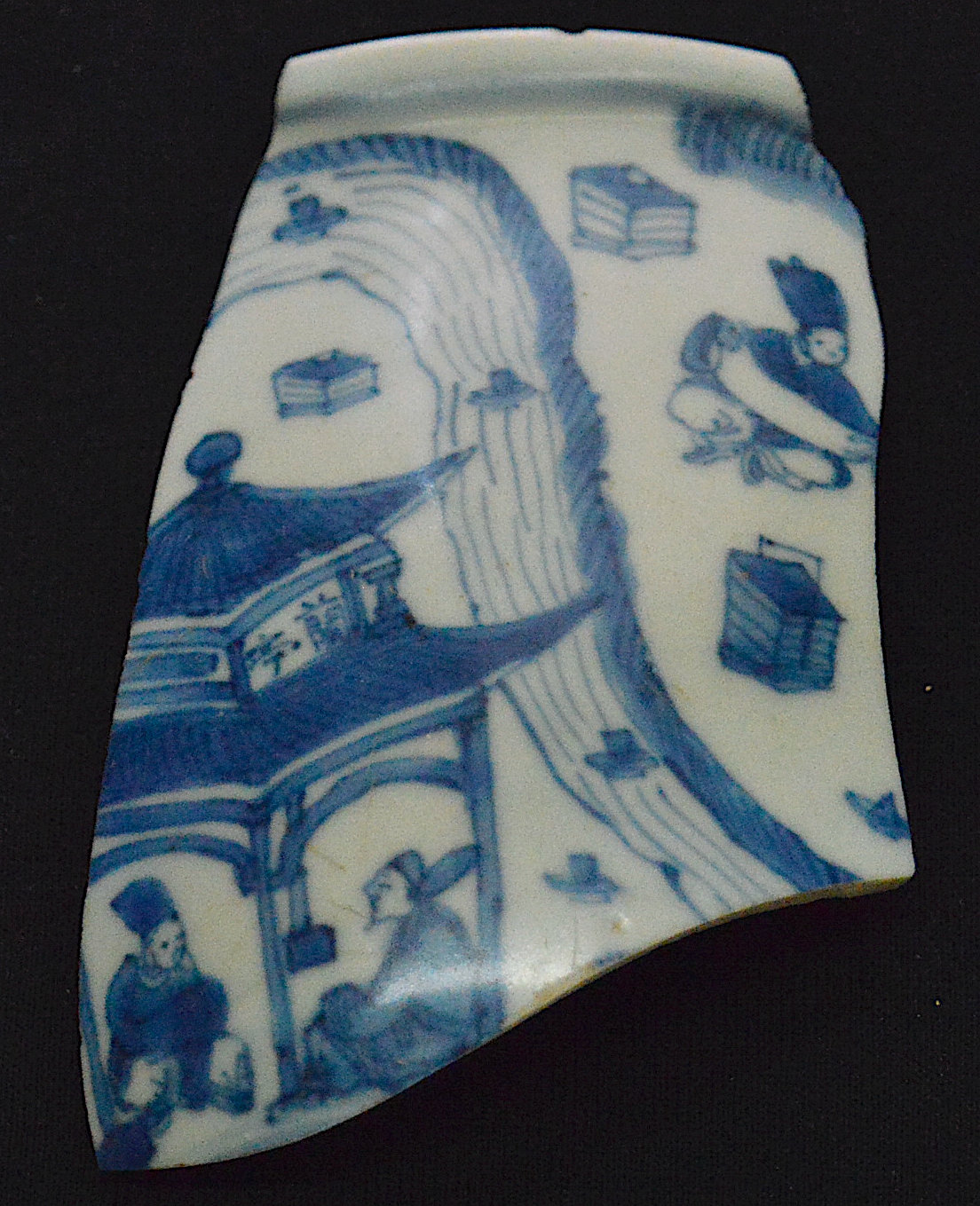

A fascinating example of the porcelain that arrived in Mexico is a sherd identified by Etsuko Miyata as the well-known scene of the poem “Lanting Xu.” The famous Chinese poem narrates an event that took place in 353 CE during the Jin dynasty (265–420) when the poet and calligrapher Wang Xizhi (303–361) gathered with fellow literati at the Orchid Pavilion to celebrate the Spring Purification ritual. They collectively composed thirty-seven poems, among which Wang wrote the “Lanting Xu,” serving as a preface to their work.22 The poem has become one of China’s masterpieces of calligraphy. Over a millennium later, this story was depicted on a blue-and-white porcelain bowl produced in Jingdezhen at the end of the Ming dynasty (fig. 10). Like many other goods, the understandings of these objects varied among the individuals who crafted them in China, those who traded them in the Philippines, and those who bought them in New Spain and beyond. Exploring these perspectives can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the interconnected societies involved.

Overall, the downtown segment of the collection contains early blue-and-white Zhangzhou pieces, fine early Wanli, typical export wares (such as the phoenix plates), and some polychromed plates and bowls, which are very similar to the ones found in Baja California and the Nan’ao 1 wreck (fig. 11). Fragments of Kraak saucer dishes, plates, small plates, bowls, bottles, dishes, ewers, klapmuts (a type of vessel), cups, boxes, and jars are present.23 One sherd was identified as having been reused as a tool for cutting. On the bottom of a phoenix plate, the foot and base were flaked on both sides to make a cutting implement. Few chocolate cups appear, a design that would become very common. Few Qing dynasty (1644–1911) pieces were recovered. No Imari or enameled pieces are present as are in Mexico City, for example. The end of the Ming dynasty in the seventeenth century interrupted porcelain production and flow to New Spain, with the Galleon bringing fewer porcelains compared to textiles, though perhaps fewer objects have been found due to different packing, unloading cargo into other spaces in the port, or having larger, more stable ships. These thoughts are inquiries to make sense of the pattern.

The sherds from the fort are very different. European decorations are abundant, as are some blue-and-white Canton wares. A few white “Dehua” pieces, such as cups, boxes, and the foot of a lion, are present. Armorial designs are but two so far: One is a small fragment, likely from a plate with a heraldic composition of a lion behind a red and gold flag; another is the body of a chocolate cup with what appears to be Ferdinand VII’s monogram (fig. 12). The design is in oxide red and gold, clearly depicting the Roman numeral VII above the letter F. A similar monogram appears in the commemorative coin of his coronation. The extraordinary thing is that Ferdinand VII became king in 1808 and had to abdicate to Napoleon’s pressure shortly thereafter. After commissioning a porcelain set in his honor, the chocolate cup would have arrived two or three years later. He became king again in late 1813, only two years before the last galleon departed Acapulco in 1815. It is almost certain that these commemorative works would have arrived in New Spain after Ferdinand’s abdication and would have thus been discarded.

Conclusions

The port of Acapulco, the origin and terminus of the Acapulco–Manila Galleon route, has been the focus of extensive archaeological work since 2015. Inspired by Manila Galleon studies, this maritime archaeology project seeks to explore the material aspects of this trade route. The project, conducted by the Underwater Archaeology Office (SAS) of INAH, has completed several field seasons and recovered a significant collection of objects. In the first five field seasons (2015–19), it recorded more than 6,500 sherds of Chinese porcelain, Asian stoneware, olive jars, Mexican majolica, and local wares, illustrating Acapulco’s trading significance and daily life through ceramics. Excavations at the fort have incorporated test pits and geophysical explorations to locate the original fort structure that collapsed in 1766 due to an earthquake. Analysis of archaeological materials has provided insights into their provenance and exchanges during this period. Preliminary analysis of the porcelain suggests that while most of it belongs to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in the Fort of San Diego, in downtown Acapulco it belongs to the sixteenth and first half of the seventeenth centuries. In the case of downtown, it could be the area of the cargo offloading, the opening of containers, and where the Acapulco Fair took place. Most of these sherds were likely pieces that arrived broken from the long journey and discarded in situ. The collection of Chinese porcelain excavated by PAMPA in Acapulco features a variety of types imported to New Spain that makes it a unique catalog of the different shapes and designs that traversed the Pacific Ocean. A detailed catalog of the collection is forthcoming.

Notes

-

Meha Priyadarshini, Chinese Porcelain in Colonial Mexico: The Material Worlds of an Early Modern Trade (Springer, 2018), 107; Ellen Hsieh, The Archaeology of Early Colonial Manila: A Hybrid City in Global History (Florida University Press, 2025), 41. ↩︎

-

William Lytle Shurz, The Manila Galleon (E. P. Dutton, 1939), 372. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 373–75. ↩︎

-

Roberto Junco, “The Archaeology of Manila Galleons,” in Proceedings on the Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage, ed. Mark Staniforth, Jennifer Craig, Sheldon Clyde Jago-on, Bobby Orillaneda, and Ligaya Lacsina (Asian Academy for Heritage Management, 2011), 877. ↩︎

-

José Luis Gasch-Tomás, “The Manila Galleons in Perspective: Notes on the History and Archaeology of the Transpacific Trade,” in Heritage and the Sea. Volume 2: Maritime History and Archaeology of the Global Iberian World (15th–18th centuries), ed. Ana Crespo Solana, Filipe Castro, and Nigel Nayling (Springer, 2022), 243. ↩︎

-

Jun Kimura, “Searching for the San Francisco (1609), a Manila Galleon Sunk off the Japanese Coast,” in Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports and Early Maritime Globalization, ed. Chunming Wu, Roberto Junco, and Liu Miao (Springer, 2019), 173; Sheldon Clyde B. Jago-on and Bobby C. Orillaneda, “Archaeological Researches on the Manila Galleon Wrecks in the Philippines,” in Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports, 129. ↩︎

-

George Kuwayama, Chinese Ceramics in Colonial Mexico (Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Hawaii University Press, 1997). ↩︎

-

Chunshui Zhou, “The Investigation and Preliminary Analysis of Nanao No. I Shipwreck in Guangdong,” in Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports, 49. ↩︎

-

Edward P. Von der Porten, Ghost Galleon: The Discovery and Archaeology of the San Juanillo on the Shores of Baja California (Texas A&M University Press, 2019). ↩︎

-

Roberto Junco, “On a Manila Galleon of the 16th Century: A Nautical Perspective,” in Early Navigation in the Asia-Pacific Region: A Maritime Archaeology Perspective, ed. Chunming Wu (Springer, 2016), 103. ↩︎

-

Roberto Junco, “Smuggling Porcelain from the Manila Galleon,” in The Archaeology of Manila Galleons in the American Continent: The Wrecks of Baja California, San Agustín, and Santo Cristo de Burgos (Oregon), ed. Scott Williams and Roberto Junco (Springer, 2021) 93. ↩︎

-

Gasch-Tomás, “The Manila Galleons in Perspective,” 235. ↩︎

-

For an overview of Chinese porcelain in Mexico as a research topic, see Patricia Fournier and Roberto Junco, “Archaeological Distribution of Chinese Porcelain in Mexico,” in Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports, 220. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 222. ↩︎

-

Guanyu Wang, “Chinese Porcelain in the Manila Galleon Trade,” in Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports, 93. ↩︎

-

Nida T. Cuevas, “Fujian and Hizen Ware: A 17th Century Evidence of the Manila Galleon Trade Found from Selected Archaeological Sites in the Philippines,” in Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports, 115; Tai-Kang Lu, “The Kraak Porcelains Discovered from Taiwan and Macao, and their Relationship with the Manila Galleon Trade,” in Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports, 147; Etsuko Miyata, “Ceramics from Nagasaki: A Link to Manila Galleon Trade,” in Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports, 161. ↩︎

-

Russell K. Skowronek, “Cinnamon, Ceramics, and Silks: Tracking the Manila Galleon Trade in the Creation of the World Economy,” in Early Navigation in the Asia-Pacific Region, 59; Karime Castillo and Patricia Fournier, “A Study of the Chinese Influence on Mexican Ceramics,” in Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports, 220. ↩︎

-

Rubén Manzanilla López and Arturo Talavera González, Las manifestaciones gráfico rupestres en los sitios arqueológicos de Acapulco (INAH, 2008), 25. ↩︎

-

Roberto Junco, “Archaeological Discoveries: The Baja California Shipwreck and the Port of Acapulco,” in Across the Pacific: Art and the Manila Galleons, ed. Alan Chong and Benjamin Chiesa (Asian Civilisations Museum, 2024), 209. ↩︎

-

Teresa Canepa, Zhangzhou Export Ceramics: The So-Called Swatow Wares (Jorge Welsh Books, 2006). ↩︎

-

For an in-depth look at these bowls and many pieces in the collection, see Teresa Canepa, Jingdezhen to the World: The Lurie Collection of Chinese Export Porcelain from the Late Ming Dynasty (Ad Ilissum, 2019), 154. See also William R. Sargent, Treasures of Chinese Export Ceramics from the Peabody Essex Museum (Peabody Essex Museum, 2012). ↩︎

-

A fragment of Wang Xizhi’s famous preface: “I am often moved by the ancients’ sentimental lines, which lamented the swiftness and uncertainty of life. When future generations look back to my time, it will probably be like how I now think of the past. What a shame! Therefore, when I list out the people that were here, and record their musings, even though times and circumstances will change, as for the things that we regret, they are the same. For the people who read this in future generations, perhaps you will likewise be moved by my words.” ↩︎

-

Teresa Canepa, Kraak Porcelain: The Rise of Global Trade in the Late 16th and Early 17th Centuries (Jorge Welsh Books, 2008), 17. ↩︎