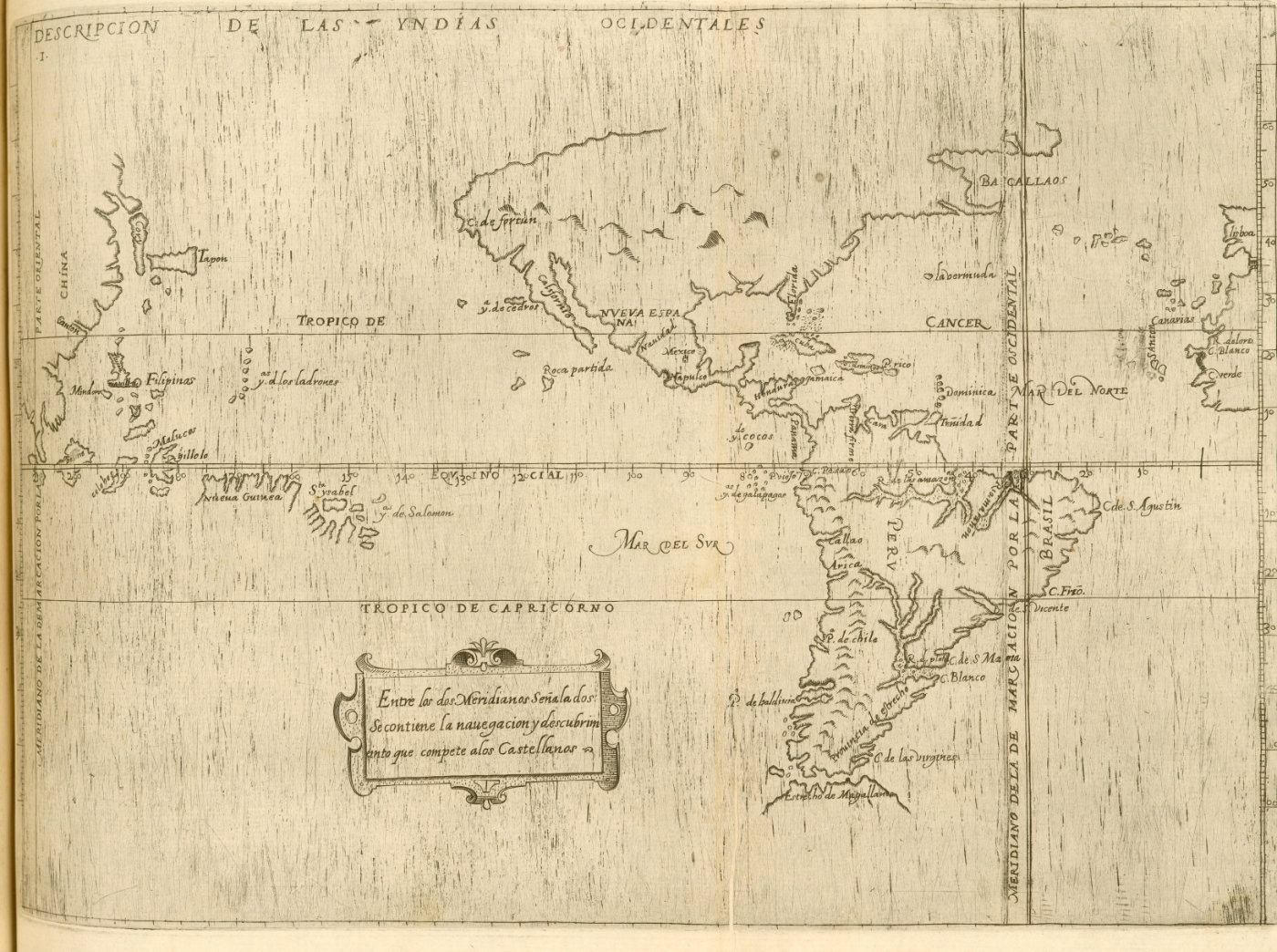

The early modern Spanish domain was an empire that, on paper, stretched across half the globe. The Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 had infamously divided most of the world in two and established the vertical meridian that separated Portuguese claims from those of the Spanish. At the moment of the treaty’s signing, Spanish overseas ambitions were oriented toward reaching Asia via the Atlantic Ocean. Of course, the American continents would prove a significant hindrance to this mission, and due to their relative proximity to the Iberian Peninsula, they would receive considerably more European contact than later colonies in Asia. Consequently, most scholars studying Spain’s empire have prioritized the American hemisphere. However, as Elizabeth Horodowich and Alexander Nagel have argued, the Americas and Asia were rarely imagined as separate entities, even late into the sixteenth century.1 The Spanish domain—extending all the way to Asia’s eastern shores—was considered contiguous (fig. 1). As such, the study of Spanish empire in the Americas cannot be conducted in isolation of the empire’s extension across the Pacific.

In the years immediately following the fall of the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan in 1521, numerous expeditions sailed into the Pacific Ocean from the Americas in search of the route to Asia.2 It would take more than forty years for Spanish ships to successfully sail back from Asia to the Americas. The first was a small vessel called the San Pedro with an Afro-Portuguese navigator named Lope Martín at the helm.3 That crossing from the Philippine archipelago to Mexico via the North Pacific in 1565 was a watershed historical moment. It made possible the establishment of a regular trade route across the Pacific between Asia and the Americas and, through this link, the founding of long-term Spanish colonies in the Philippines. As scholars of the Spanish Pacific have made abundantly clear, these developments would have enormous economic, demographic, and cultural repercussions for both sides of the ocean.4

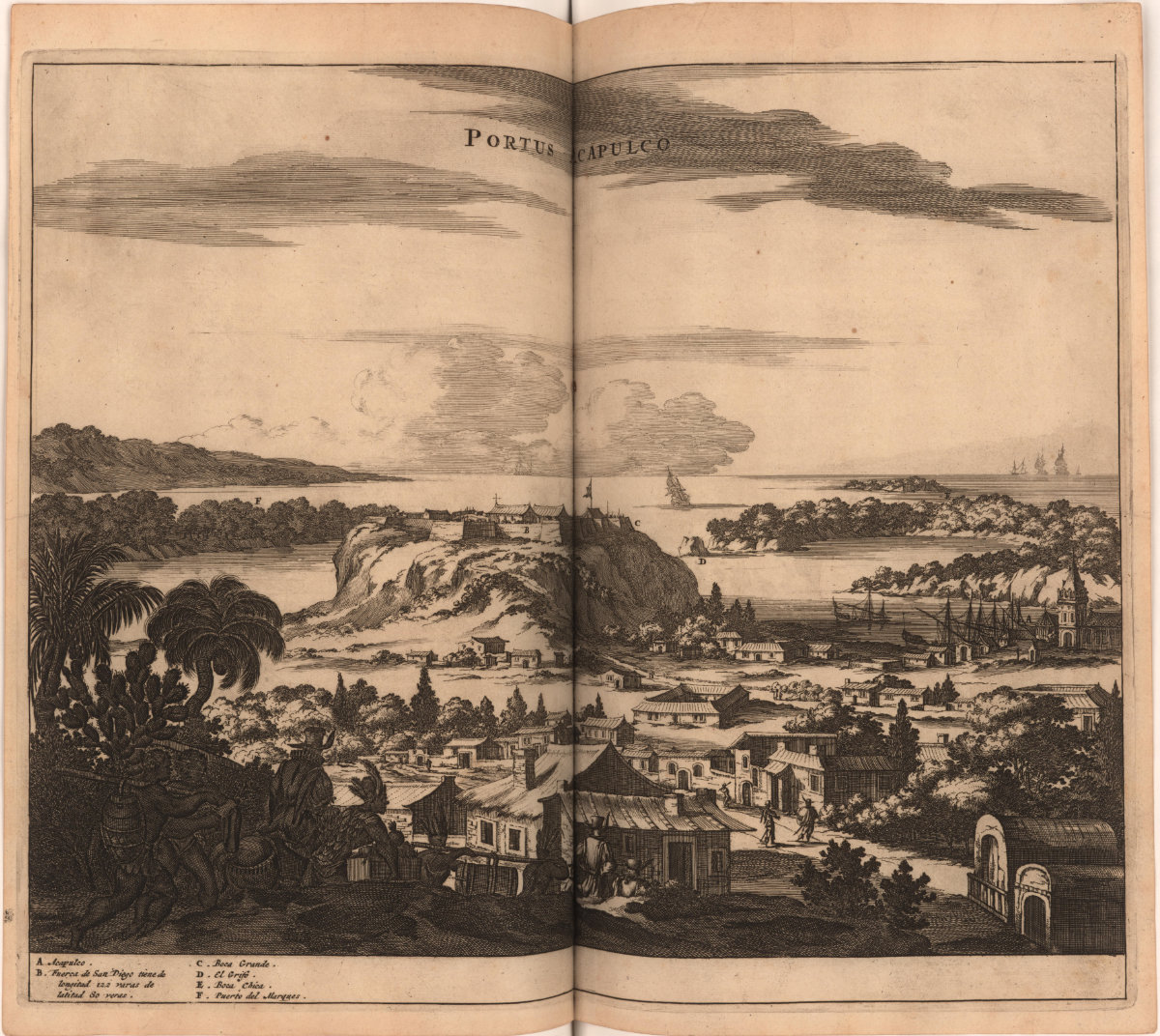

The Spanish ships that sailed this transpacific trade route from Cavite, Philippines, to Acapulco, Mexico, are called the Manila galleons, and they operated from 1571 to 1815 (fig. 2).5 Since the publication of William Schurz’s landmark book, The Manila Galleon, in 1939, scholarship on these ships has developed mainly in two directions.6 First, there is the trade itself, the material circulation at the heart of transpacific colonialism and the principal reason Spaniards in Mexico invested so heavily in colonial ventures in the Philippines. Silver mined by coerced and often enslaved Indigenous, African, and Afro-descended laborers in the Americas flowed across the Pacific. Through predominantly Fujianese merchants in Manila’s Parián (Chinese quarter), that silver ended up not only on the Chinese mainland but throughout the region.7 In return, merchants, sailors, and elites brought back precious porcelainware, refined and unrefined silk, textiles, furniture, devotional images, and much more for consumers in the Americas and western Europe. This trade fueled the emergence and coherence of a truly global economy that regularly connected all oceans in both directions for the first time in world history.8

Second, the ships conveying trade goods simultaneously facilitated the movement of European, Indigenous, African, Afro-descended, Asian, Pacific Islander, and multiracial people in both directions across the Pacific. Some of these populations were transient, while others settled permanently far from their homelands. In my previous work, I have studied the movement of over twenty thousand free and enslaved Asians to the Americas, which long predated the conventional nineteenth-century origins of Asian migration to the Western Hemisphere.9 Much work remains to be done to follow the mobility of Indigenous and Black people from the Americas into the Pacific.

Traditionally, the themes of global trade and human mobility have been siloed as separate fields with limited overlap. One either studies objects or people, not both. In part, this bifurcation is not just a problem of disciplinary boundaries but one of archives. The very sources documenting the crates upon crates of Asian wares entering Acapulco silence or, at best, vastly minimize the presence, activities, and subjectivities of marginalized colonial subjects. Yet, these subjects were there, always just out of frame. On the galleons and even after disembarkation, the histories of goods and the people who handled them were, indeed, deeply entangled. In the case of the enslaved, humans were the commercial products. People were bought and sold alongside precious porcelain. From the late sixteenth to late seventeenth centuries, Déborah Oropeza estimates that anywhere between 3,776 and 10,000 enslaved Asians arrived in Mexico on the galleons.10 These numbers do not include the transpacific trafficking in Africans and Afro-descendants that persisted into the eighteenth century after the abolition of chino (Asian) enslavement in 1672.11 That the Manila galleons were slave ships should add a wrinkle to grandiose narratives that unflinchingly celebrate the arrival of luxurious Asian goods in the Americas.

More broadly, the commercial value of transpacific trade had an immeasurable impact on the experiences of people crossing the world’s largest ocean. On the galleons, everyone from the ship’s commander and navigator down to the poorest sailors carried goods from the Philippines to be sold in Acapulco or anywhere from Mexico to Peru. In fact, the opportunity to sell a trunk of Asian wares after disembarking was a major incentive for sailors to risk their lives crossing the Pacific. The route left so many dead that such a policy was necessary to keep the ships fully staffed.12

The voyage from the Philippines to Mexico typically lasted an excruciating five to six months, sometimes more, sometimes less. The ships navigated from Cavite and through the Visayas before exiting the Philippine archipelago through the Embocadero and rising to the latitude of Japan to cross the tumultuous North Pacific eastward. Then, after spotting Cape Mendocino in California, they dropped south past Baja California—careful to avoid the rocky coast—until hitting Mazatlán to the east and continuing south. Finally, the ships sailed into the protected Bay of Acapulco and anchored under the guns of the Fort of San Diego (fig. 3).

Free and enslaved Asian sailors were almost always the majority on Spanish ships sailing this route. Most served as grumetes (cabin boys); that is to say, they were the lowest-ranking crew members who received the lowest pay and rations. While most grumetes were from Luzon in the Philippines, a handful originated from elsewhere in coastal Asia. Meanwhile, most of the enslaved—who also performed sailing duties onboard—were either from South Asia or elsewhere in the Philippines. The survival of all and the maintenance of transpacific trade depended on the labor of these grumetes and the enslaved.13

The experience of sailing on a transpacific galleon was unlike that of any other early modern Spanish trade route, precisely because of the high valuation of galleon cargos. In 1605, Hernando de los Ríos Coronel wrote that galleon commanders would overload their ships with trade goods to maximize the profit of each voyage despite royal orders capping the value of the cargo. Consequently, there was very little room below the deck to accommodate people. Only a privileged few could afford to rent a cabin. The rest, including the grumetes and the enslaved, slept exposed to the elements, either partially under one of the galleons’ two superstructures or simply uncovered on the deck itself. Many froze in the North Pacific.14

Full cargos meant that galleons often sailed with low stocks of food as well. According to Coronel, galleon officials often stored what food there was topside, where storms often swept it away. Sailors and officers were expected to supplement shipboard rations with their own supplies. The wealthier brought aboard live animals. The rest subsisted on a little fresh food during the first month of the voyage and then maggoty rice and hardtack during the rest. Malnourished sailors also fished on calm days and snared unfortunate birds resting their wings on the ship. Inevitably, crew members without access to live animals developed scurvy, dysentery, and beriberi by the end of the voyage.15 People were considered expendable; valuable goods were not.

The problem of lading space was so severe that cannons were similarly an afterthought. Galleons beset by privateers lacked the means to fight back. The most extreme example of this reality was the fate of the San Diego, a fully loaded galleon that brought aboard cannons to fight off the Dutch Oliver van Noort’s attack on Manila in 1600. Under the command of the chronicler Antonio de Morga, the vessel sailed in pursuit of the Mauritius, the Dutch flagship. The weight of merchandise, cannons, and three hundred to four hundred soldiers and sailors contributed to the San Diego’s sudden sinking during combat despite successfully boarding the enemy vessel. Interestingly enough, merchandise recovered from the wreck of the San Diego during the 1990s remains one of the best sources to visualize the vast scope of the cargo on the Manila galleons (figs. 4 and 5).16

All of these factors contributed to the immense loss of life that became a defining reality of the transpacific crossing. It was not unusual for a “successful voyage” to lose 30 percent or more of its crew. When Pedro Cubero Sebastián made the crossing toward the end of the seventeenth century, only 192 of the original 400 onboard survived. Similarly, in 1616, 150 out of the ship’s 200 crew members died, primarily due to a lack of provisions.17 Survivors were often hospitalized for months in Acapulco, and some failed to return to health and perished on land. In total, thousands died, though no reliable estimates of casualties exist. This was the true cost of the transpacific trade. People were made to give their lives for every Asian product unloaded in Mexico.

After disembarkation at Acapulco, following the confluence of objects and people leads us to other unexpected histories beyond formal sites of exchange at trade fairs and urban plazas. In fact, much of the cargo changed hands through informal means. Outside of the marketplace, non-elites gained access to Asian products. Middling merchants led mule trains through the central Mexican highlands, up the coast to Zihuatanejo, and further north to Guadalajara. On the way, they passed through smaller pueblos de indios (Indigenous towns) and peddled their wares to buyers with access to silver coins, cacao beans, and other goods for barter. One of these many merchants was Domingo de Villalobos, a thirty-one-year-old Kapampangan man from the Philippines. He lived on the Colima–Guadalajara trade corridor in Tzapotlan (also Zapotlán). From his will in 1618, we can approximate the inventory that these informal traders brought to small towns and scattered populations outside of urban centers in central Mexico:

Inventory

9 mules

-

56 sinabafas (a type of linen fabric) with a sack

-

49 lanquines (cloth or silk textiles or clothing, associated with the Chinese city of “Lanquin” [Nanjing]) with a sack18

-

8 pieces of taffeta from china (Asia) with a piece of damask

32 pairs of cotton socks from china

a blue-patterned silk pincushion pillow

16 cotton laces from china

-

a dark coat with tawny and purple decoration

24 breeches

a doublet

-

a cloak decorated with green trimming and with a fabric jerkin

-

7 varas (yard-lengths) of wool-blend fabric

-

1½ varas of taffeta of the land (from Mexico)

3 varas of material to make footware

-

4 ounces of purple and tawny trimmings with buttons and silk

-

some silk-cloth breeches with a chamois leather jerkin

a sword and dagger with belt and bullets

-

2 pairs of socks from Castille (1 tawny pair and 1 white pair)

-

2 high-quality garters, 1 colorful and 1 from Japan

a Japanese sash embroidered with silk

a worn outer garment

2 hats with their fastenings

-

a stuffed mattress with wool covering and pillow with 2 pairs of blankets (1 still being made)

-

4 pairs of shirts (2 still being made), 6 of coarse woolen cloth

-

a harquebus with a powder flask and a smaller flask with a small pistol with its flask

a katana

-

2 tanned deerskin pouches with iron fittings

5 bundles of feathers for a girl

-

several colorful cotton petticoats from Pampanga

-

silk breeches from china with several green silk socks from Castille

-

2 pieces of fine linen cloth from china with their tail and cord

5 scarves of sinabafa

-

180 pesos in reales (100 of which are in the possession of Alonso Gutiérrez; 8 reales equaled 1 peso)

-

40 bushels of salt bought from Alonso Gutiérrez

-

a shipment of cacao in the possession of Nicolas Rodríguez from Maquili

-

owed debt to Gaspar Sánchez (1 peso, 1 tomín)

10 bushels of corn

a hairband with 43 gold brooches

13 sacks (11 new, 2 old)

a new tent from Lanquin

-

an armored riding seat with saddle strap and iron stirrups

-

a woolen covering with a deerskin decoration

a horse headstall with its bit

a pillion with its breast strap

a silver Agnus Dei figure

a rosary

a little coarse cloth

2 new ropes with 10 knots

7 worn ropes with their knots

-

a 6-handspan large box with a padlock in Acapulco in the house of Agustín Pampango chino

3 collars with hoods made of thick wool

5 big nets

4 pounds of cinnamon

-

10 pounds and 4 ounces of white wax from china in loaves

-

debts owed by Pedro Pablo (13 pesos for 6 varas of velvet), Alonso Garrucho (2 shipments of cacao), Pedro Moreno, Francisco Luis chino (owed clothing), Gaspar Necio (25 pesos), the heirs of Andrés García from Colima (17 pesos, 4 tomines [worth ⅛ peso each]), Chavos indio (4 pesos, 2 tomines), Jorge Carrillo (12 pesos for cotton cloth), Alonso mulato (3 pesos for a hat), Nicolas Malanquiz chino (10 pesos for salt), Pedro Timban (3 pesos for a bushel of salt), Sebastián (2 pesos, 4 tomines), María Vázquez (3 pesos, 1 tomín for cotton cloth and 10 tomines for a silver knife), Juan Triana chino (2 pesos, 4 tomines for clothing), Juan Botete (3 pesos for clothing), Agustín Solampao (1 peso, 6 tomines in reales for cacao), Alonso Ramos (5 pesos), and Francisco Mathias chino (4 pesos, 4 tomines), don Francisco (12 bushels of salt), Andrés Malate chino (10 pesos), Andrés alcalde (magistrate) (2 bushels of salt), Juan Simentro (2½ bushels of salt), Catalina Tuxpaneca (2½ bushels of salt and 10 tomines in cacao), Francisco de Atecosahuic (3 pesos), Madalena Cecilia (1 peso), Pedro Timban (4 pesos of earrings), Pedro de Atlacosahuic (1½ pesos), and Miguel Capisayo (1 bushel of salt) 19

The inventory makes clear that Villalobos was a socially mobile, even fashionable, chino merchant operating in rural zones of Nueva Galicia to the northwest of Mexico City. He owed his commercial success to trade in both local commodities and Asian products. For example, he had large quantities of salt either in his possession, in that of intermediaries, or owed to him. Salt flowed from the Pacific coasts to Indigenous consumers in the highlands, and Villalobos was clearly an agent of this trade.20

However, of particular interest here are his dealings in Asian goods, which were primarily fabrics and clothing, including Chinese cotton, silks, and taffeta. Acapulco was the source of these products, where Villalobos had a contact, a fellow Kapampangan man named Agustín. Villalobos likely traveled with his nine mules and a horse to the port when galleons were anchored in the bay to make purchases for rural consumers desiring to craft their own clothing using Chinese silks and wool.

Villalobos seems to have kept the best items for himself, though. He must have struck quite an image rolling into town with a purple-trimmed cloak, leather jerkin, silk breeches, Japanese garters, a silk-embroidered Japanese sash, Chinese-cotton socks, hat, and a katana on his sword belt. Then again, other merchants with access to Acapulco had finery of this quality as well.

From his homeland, Villalobos kept only several petticoats that he described as “colorful” and made of “cotton.” These items clearly had sentimental value. When Villalobos fell sick, he stayed in the house of his close business associate (and likely friend), a fellow Kapampangan man named Alonso Gutiérrez. Gutiérrez’s wife, an Indigenous woman named doña Mariana, nursed Villalobos back to health. When he recovered, Villalobos publicly gifted one of these petticoats to doña Mariana.21 Sadly, Villalobos relapsed into illness and returned to Gutiérrez’s home, where he was bedridden for seven months before passing away.22

As exceptional as a character like Villalobos might initially seem, his will makes abundantly clear that there were many other Kapampangan and Asian merchants operating in pueblos de indios in colonial Mexico. Like other mule train drivers connected to Acapulco, they facilitated the wide dispersion of Asian products to communities otherwise unlikely to buy the finest wares at the main plaza in Mexico City. In this case, diasporic Philippine networks made such exchanges possible.23

The entanglement of the movement of goods and people extended across the Atlantic to Spain as well. In 1623, a prominent Spanish judge in Mexico hired a Japanese man named Juan Antonio to accompany a Japanese bed being shipped as a gift to the recently crowned Spanish king, Philip IV.24 His predecessors, Philip II and Philip III, had already hosted impressive Japanese embassies traveling to Rome and received lavish gifts that can still be seen in the Real Armería (Royal Armory) in Madrid today. Upon arrival at the royal court, Juan Antonio presented the king with a letter from the judge stating that this man could repair the bed if it had arrived damaged. He could also fix biombos (Japanese screen panels) or any other Japanese product. In the king’s presence, Juan Antonio assembled the bed (fig. 6).

However, the rest of his stay in Spain would be nothing so glamorous. Like many Asian subjects who arrived at the seat of the empire, Juan Antonio soon found himself stranded with no means of returning overseas. He was merely a disposable accessory to the judge’s gift. Subsequently, Juan Antonio submitted multiple petitions to the Crown begging for employment as a soldier, an interpreter, and eventually, as a sailor so that he could earn enough money to return to Mexico.25 For him, there was no separating material fascination with Asian products from his long-distance displacement. His entire existence had been reduced to the service of a gift.

The disciplinary boundaries that often silo the study of objects and people have obscured the extent to which both were historically inseparable. Searching for their many intersections brings us to understudied histories, like the harrowing nature of the Pacific passage, the mule trains crisscrossing colonial Mexican hinterlands, and the rare case of a Japanese man accompanying a bed sent to the king of Spain. These examples merely scratch the surface, but in their brevity, they also prove that the texture of history—the lived experience of it—constantly and triumphantly resists the fragile categories we are trained to harness it with. I find it more liberating to surrender to the innumerable ways the messiness of history challenges the way we think, with its fantastical idiosyncrasies. To study the storied galleons and the ways in which the transpacific trade remade the early modern world is to embark on an inward journey—alongside that of our historical subjects—because the value of doing history is not simply in reassembling the past into new configurations but, rather, in how it forces us to constantly reform the tools we deploy to perceive our world and its past.

Notes

-

Elizabeth Horodowich and Alexander Nagel, Amerasia (Zone Books, 2023), 14. ↩︎

-

Guillaume Gaudin, “On the Legal Grounds of the Conquest of the Philippines (1568),” in The Spanish Pacific, 1521–1815, Volume 2: A Reader of Primary Sources, ed. Christina H. Lee and Ricardo Padrón (Amsterdam University Press, 2024), 97–99. ↩︎

-

Andrés Reséndez, Conquering the Pacific: An Unknown Mariner and the Final Great Voyage of the Age of Discovery (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021). ↩︎

-

For a summary, see Ryan Dominic Crewe, “Connecting the Indies: The Hispano-Asian Pacific World in Early Modern Global History,” Estudios Históricos 30, no. 60 (2017): 17–34; Lee and Padrón, “Introduction,” in The Spanish Pacific, 1521–1815, 9–20. ↩︎

-

In Spanish, the vessels were called naos de china (Asia ships). On “Manila galleons” as a misnomer, see Diego Javier Luis, The First Asians in the Americas: A Transpacific History (Harvard University Press, 2024), 8. ↩︎

-

William Lytle Schurz, The Manila Galleon: Illustrated with Maps (E. P. Dutton, 1939). ↩︎

-

For the most complete study of Manila’s Chinese community and their economic activities, see Juan Gil, Los chinos en Manila: Siglos XVI y XVII (Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau, 2011). ↩︎

-

Arturo Giráldez, The Age of Trade: The Manila Galleons and the Dawn of the Global Economy (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 2–3. ↩︎

-

For an analysis of numbers regarding early modern Asian mobility to the Americas, see Luis, The First Asians in the Americas, 15. ↩︎

-

Déborah Oropeza, La migración asiática en el virreinato de la Nueva España: Un proceso de globalización (1565-1815) (El Colegio de México, 2020), 151; Luis, The First Asians in the Americas, 15. ↩︎

-

Pablo Miguel Sierra Silva, Mexico, Slavery, Freedom: A Bilingual Documentary History, 1520–1829 (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2024), 92, 104–7. ↩︎

-

Luis, The First Asians in the Americas, 92–93. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 76. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 68, 79–80. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 78. ↩︎

-

Jose M. Buhain, “The Recovery of the San Diego,” Philippine Studies 42, no. 4 (1994): 543–48. ↩︎

-

Luis, The First Asians in the Americas, 78. ↩︎

-

Andreia Martins Torres, “Quimonos chinos y quimones criollos. La moda novohispana en el cruce entre Oriente y Occidente,” in La nao de China, 1565-1815: Navegación, comercio e intercambios culturales, ed. Salvador Bernabéu Albert (Universidad de Sevilla, Secretariado de Publicaciones, 2013), 261–62. ↩︎

-

“Bienes de difuntos: Domingo de Villalobos,” 1621, Archivo General de Indias (AGI), Contratación, 520, N.2, R.14, ff. 31r–46r. ↩︎

-

Jonathan D. Amith, The Möbius Strip: A Spatial History of Colonial Society in Guerrero, Mexico (Stanford University Press, 2005), 65–66. ↩︎

-

“Bienes de difuntos: Domingo de Villalobos,” 1621, Archivo General de Indias (AGI), Contratación, 520, N.2, R.14, f. 130v. ↩︎

-

Luis, The First Asians in the Americas, 129–32. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 17. ↩︎

-

“Decreto enviando petición del japonés Juan Antonio,” 1624, Archivo General de Indias (AGI), Filipinas, 39, N.21. ↩︎

-

“Petición del japonés Juan Antonio de que se le nombre intérprete,” 1624, Archivo General de Indias (AGI), Filipinas, 39, N.23; “Petición del japonés Juan Antonio de licencia para ir a Nueva España,” 1624, Archivo General de Indias (AGI), Filipinas, 39, N.24; Ibid., 195–96. ↩︎